Why 2018 marks a critical milestone in China-Africa relations

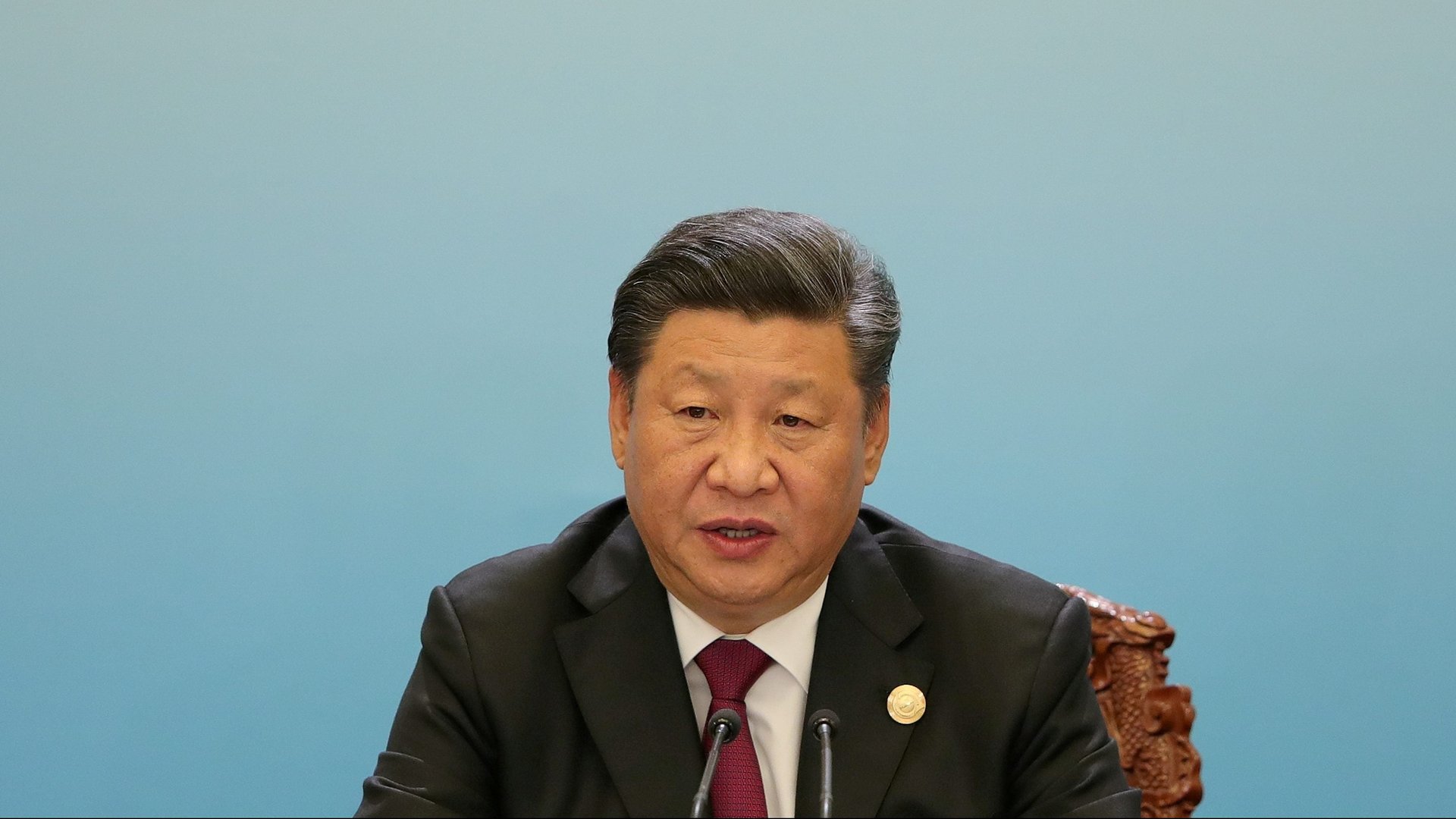

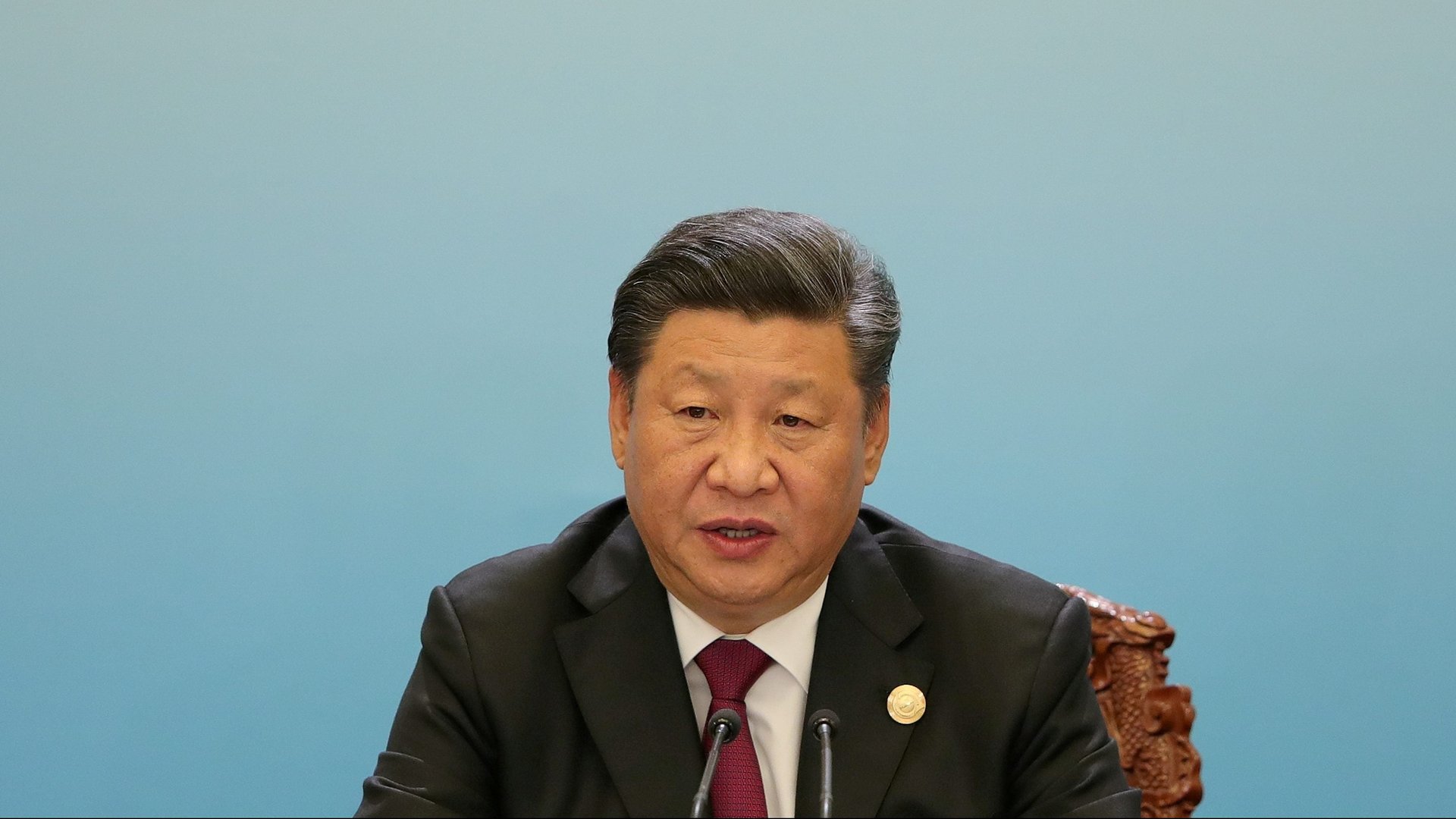

Leaders from all African nations, except for eSwatini, attended the 2018 Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Beijing this past week. There, Chinese president Xi Jinping pledged $60 billion to the continent in loans, grants, and development financing. Xi also announced eight initiatives aimed at improving Sino-Africa relations, including investments in healthcare, education, security, cultural exchanges, and increasing non-resource imports from Africa.

Leaders from all African nations, except for eSwatini, attended the 2018 Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Beijing this past week. There, Chinese president Xi Jinping pledged $60 billion to the continent in loans, grants, and development financing. Xi also announced eight initiatives aimed at improving Sino-Africa relations, including investments in healthcare, education, security, cultural exchanges, and increasing non-resource imports from Africa.

The conference happened against a backdrop of growing scrutiny of Beijing’s lending practices. Critics have argued that China’s Belt and Road initiative, modeled on the old Silk Road, was a giant “debt trap” and akin to “neocolonialism.” Observers also noted the Asian superpower wasn’t being straightforward about whether it fulfilled all the amounts it previously committed to African states. The $60 billion financial commitment in 2018 was also an aberration from China’s pattern to double or triple pledges every three years: from $5 billion in 2006 to $60 billion in 2015.

FOCAC also took place as Beijing faces increasing local and international pressures including a total debt that has ballooned from $6 trillion in 2008 to $28 trillion by 2017. There’s also the ongoing trade war with the US, the growing pressures on the yuan, besides domestic criticism that the government needed these finances to improve Chinese lives. Beijing is also facing increasing censure from institutions like the IMF for not being a member of the Paris Club, the multilateral group of official sovereign creditors.

Pushing back against some of these sentiments, Xi argued at the summit that Chinese money was not being spent on “vanity projects” in Africa.

Given all this, China might become “stringent” and cautious in extending loans to Africa, says W. Gyude Moore, a former Liberian minister and a visiting fellow at the Center for Global Development in Washington DC. And while China has always provided quick, no-strings-attached loans that set fewer conditions to African states, Moore says that’s going to be difficult to undertake if Beijing “is also saying that they are going to do projects that are sustainable.”

The onus will then be on African governments—who owe a lot of debt not just to Beijing but also to commercial and traditional lenders like the World Bank—to clearly define their development agendas. In seeking Chinese finance, there will need to be increased quality in project selection and implementation. To dispel skepticism around the commercial viability of projects, governments could also submit regional projects together, hence driving both economic and political integration in the long run. To boost cooling trade figures, there’s need to also improve regulations, promote the private sector, and diversify African brand exports to China.

In this changing climate, it will be prudent for African leaders to not just voice adulations towards China but to actually know what they want.

Moore doesn’t think “the Chinese spigot is going to completely turn off, but it’s going to slow down.” And that, he adds, presents “an opportunity for African countries to look for the policy decisions and options that will allow them to grow their economies.”