Does foreign aid work? Spectacularly well in the case of health interventions such as eradicating polio or super-charging Korea’s war-torn economy (paywall). But billions of dollars in development aid may be wasted each year, if it’s tracked at all.

Rather than expand government-run programs, researchers are testing if giving cash directly to the poor might be better. Initial results are promising. A new study released on Sept. 13 by Craig McIntosh at the University of California San Diego and Andrew Zeitlin at Georgetown University, may help push governments to reprioritize how cash is used for the roughly $130 billion (paywall) in aid each year.

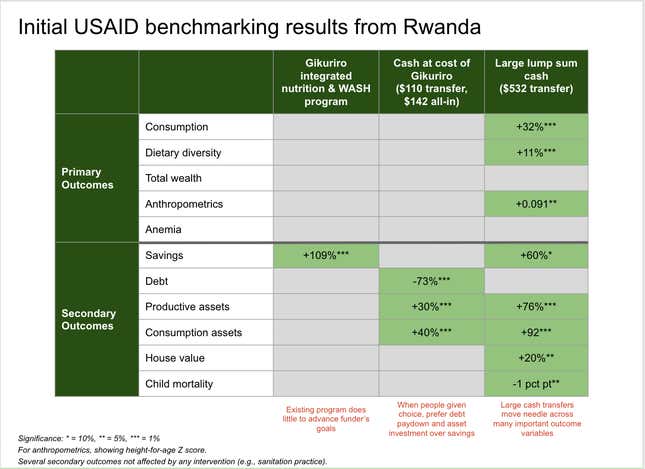

The study tracked the Gikuriro program (meaning ‘well-growing child’ in Kinyarwanda) across 248 villages in Rwanda. Villages received one of four interventions: a standard USAID-funded water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) program; a distribution of small grants up to $142; one large payment of $532; or no program at all. Cash came from USAID and Google.org, and was distributed by US nonprofit GiveDirectly as mobile payments. Catholic Relief Services administered the aid program. Researchers measured changes to household savings, consumption, diet, anemia rates, child growth, and net wealth.

Cash conquered all. Neither the traditional program nor the cash-equivalent transfer ($142) achieved any of its primary goals of improving children’s health in households at risk for malnutrition. Diet, health, household consumption and wealth were all unaffected, as was the control group. The Gikuriro program only increased savings and vaccination rates, while the small cash transfer increased household assets and lowered debts, all secondary effects. The real payoff came from those receiving the large $532 payment: consumption, savings, assets, and house values all increased, along with improvements in diet and child mortality.

Those results may seem intuitive, but co-author McIntosh calls it almost “revolutionary” in how it diverges from the way most aid is spent. “You should be tipping the scale to doing more for fewer people, and toward the idea that the lion share of resources should go to direct nutritional support” either in cash or food, said MacIntosh. Often, it’s not information that’s needed, it’s financial resources to act. That suggests water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programs could devote less of their resources to education and behavior change, and more to direct support.

Of course, the study is just a starting point. The study lasted one year and the effects observed were small, if statistically significant. The study also did not test better-funded aid projects more analogous to a large cash grant. More research will be needed to draw definitive conclusions.

Michael Faye, president of GiveDirectly, said it plans to replicate the evaluation in three more countries with USAID. It wants to see cash accepted as a benchmark for aid projects in the future. While Faye acknowledged cash will never be a silver bullet (aid programs with larger budgets have been shown to be effective), he says cash can become the baseline to beat.