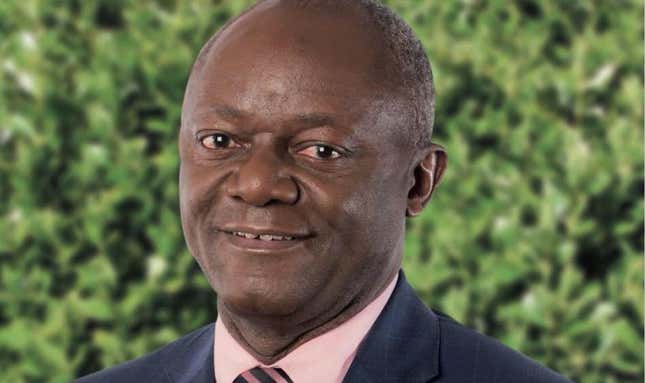

Belgian voters have elected their first black mayor, who also happens to be father of one of the country’s best known footballers. Pierre Kompany, though, doesn’t want to be known for his son’s fame or his race, he just wants to be a local representative.

Kompany, father of Manchester City captain and national player Vincent Kompany, was elected mayor of the Ganshoren, a Brussels borough of about 25,000 people. While Kompany’s campaign avoided identity and racial politics, the local election is being celebrated as a moment of racial progress in Belgium. For some in the small but growing black community, the Sunday election win feels like they finally have a place in Belgium.

Footballer Vincent Kompany and his brother Francois (who plays for the local league) congratulated their dad on social media, celebrating his election as historic. Last week, Kompany tweeted an image of the Belgian parliament, lamenting the lack of diversity in politics, business and media.

“I’m especially proud, and so is the whole Congolese community, that a black man was directly elected by Belgians in a city like Ganshoren, which has maybe 100 people of Congolese origin,” local historian Mathieu Zana Etambala, told the New York Times.

The colonialism academic also added that Kompany’s win “marks the undeniable presence of the Congolese here in Belgium,” where the population of 120,000 remains relatively low thanks to restrictive immigration policies. Belgium is only now beginning to face the brutal colonial legacy that wiped out about a third of the Congo’s population, while it enriched King Leopold II’s country. Today, race relations in the country are beginning to bubble to the surface, exposing the lack of progress.

Kompany arrived in Belgium in 1975, as a student fleeing Mobutu Sese Seko’s regime. In the then Zaire, he’d been imprisoned for over a year for his role in protests against the dictator. In Belgium as a refugee, he drove a taxi for five years to pay for his studies, completing his engineering degree at the age of 34.

Kompany was undocumented for eight years, and recalls not being allowed to enter the dance hall because he was black (link in Dutch). From his son’s account, life wasn’t easy. Kompany’s marriage fell apart, he lost his job, his son was kicked out of school and lost his place in the Belgian youth team.

He entered city politics in 2006 when he was elected as a councilor and then won a seat in the Brussels regional parliament in 2014.

Still, he wants to resist the “Obama of Brussels” label reporters have tried to stick on him and has refused to publicly endorse his son’s statement that “it was time” a black candidate was elected, avoiding any overt references to race (link in Dutch).

While his win is celebrated nationally, Kompany ran an independent campaign on very local issues such as childcare, elderly assistance and of course, improved soccer fields. He is adamant that he doesn’t want his experiences as a black man in Belgium to be turned into an exception. Yet, Kompany is already the model minority, the against-the-odds story who made it in spite of his race, but will never quite be free of that burden.