The successful development of a drug for the treatment of a sickle cell anaemia using a traditional herbal remedy by Nigerian scientists was widely regarded as a very significant breakthrough in medicine in 1998. Before Niprisan there was only one approved sickle cell drug (Hydroxyurea) but it was bogged down with multiple concerns about its toxic and carcinogenic side effects on patients.

But the commercialization of Niprisan, even with a potential market opportunity estimated to worth over $1 billion, has been mired in controversy for over a decade. It has ended up denying millions of people affected by the scourge of the disorder an opportunity of having a better life.

Sickle cell anaemia affects over 12 million people, mostly with origins in sub-Saharan Africa, India, Saudi Arabia and Mediterranean countries The disease is regarded as a silent baby killer as an estimated 50% to 80% of infants born with the disorder die before the age of 5 years. Each year about 300 000 infants are born with major sickle-cell disorders—including more than 200 000 cases in Africa, according to WHO. In Nigeria alone, about 150 000 children are born annually with the disorder.

Niprisan was developed by Nigeria’s National Institute for Pharmaceutical Research and Development (NIPRD) from one of the many traditional herbal medicines that have been used for treating the disorder in Nigeria long before colonization. The new drug was a product of the advocacy for a collaboration between scientists and local traditional herbal healers to develop drugs from Africa’s rich biodiversity and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants.

It is also one of the first herbal medicinal products in Nigeria to have been successfully developed, patented (a US patent was approved in September 1998), and passed through clinical studies.

The research and development of the drug didn’t only produce a medicinal value, it also led to the development of local pharmaceutical capacity in research, preclinical tests and clinical trial. It also produced economic value thanks to the patent acquired. This is seen as a vital step as Africa’s centuries-old herbal treatments and indigenous medicinal plants cannot be patented in their natural form.

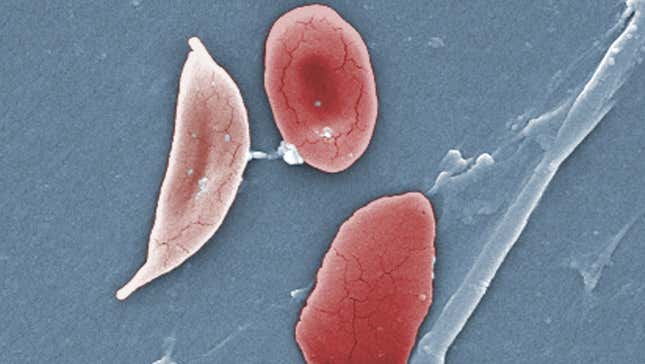

Sickle cell anaemia is a genetic disorder in which the red blood cells become rigid and sticky and are shaped like sickles or crescent moons as such they don’t flow easily, and they can get stuck in the small blood vessels. This can cause a Sickle cell “crisis”, an intense, unbearable pain all over the body that can last from a few hours to as long as a few weeks. It usually occurs when the sickled cells get stuck and slow or even totally block blood flow, so some parts of the body don’t get the oxygen they need.

Niprisan, which is a phytochemical formulated from parts of four different indigenous plants (Piper guineenses seeds, Pterocarpus osun stem, Eugenia caryophylum fruit and Sorghum bicolor leaves) is not a cure for Sickle cell anaemia but significantly reduces the occurrence of crises without any toxicity or serious adverse events on patients.

The drug works by reversing the sickling of red blood cells and protects them from becoming sickled when exposed to low oxygen tension. The drug has proved to be potent in managing sickle-cell disorder in patents, but it is also important that it is affordable and available in those who need it.

Unfortunately, the commercialization of Niprisan got hampered by several challenges. The first issue was the lack of pharmaceutical capacity for drug formulation in Nigeria. It was reported that finding a commercial partner in Nigeria to scale up and manufacture of Niprisan proved difficult.

The Nigerian pharmaceutical industry has long been focused on marketing and distribution of internationally licensed drugs and as such the exclusive rights to the patent were eventually sold to a US-based, Indian-owned company Xechem International in 2003. It was a deal that led to the first controversy around the drug.

Xechem successfully secured an “orphan drug” status for Niprisan in the United States in 2004 and in the European Union in 2005—qualifying it for financial incentives to produce drugs considered unprofitable to develop. It then launched the product into the Nigerian market as Nicosan in 2006.

But in the years that followed Xechem International and its Nigerian company, Xechem Nigeria became engulfed in series of mismanagement and corruption allegations, and litigation cases both in the US and Nigeria.

It didn’t help that after being introduced into the market, as reported, only 10,000 to 15,000 capsules a day were produced from limited facilities. This meant the drug was scarce and expensive for locals at $25 per month supply. Even though several bank loans of millions of dollars were secured, Xechem Nigeria was unable to scale up operations to its 50,000 capsules a day target.

Xechem International later filed for bankruptcy protection in the United States in November 2008. After production slowed down the exclusive license given to Xechem International for the manufacture and marketing of the drug was withdrawn in March 2009. The Nigerian government took over production through NIPRD but that plan didn’t last long and commercial production of the drug was later stopped in 2015.

After the patent expired in 2017, Niprisan could be produced as a generic drug. An Illinois pharmaceutical company, Xickle already currently sells its own version of the drug building on the work of the original Nigerian version. The company has claimed its drug has twice the anti-sickling activity of the original but a single bottle of Xickle (one month’s supply) is $99—much higher than patients in low-income African countries can afford.

One of the hopes of developing and marketing a drug locally in Africa is that it would have a lower cost base and thereby be more affordable for a disease which mostly afflicts people in the region than elsewhere. As noted earlier, the local version of Niprisan, marketed as Nicosan, sold for around $25 and was still considered expensive for most.

There seems to be light at the end of the tunnel for the commercialization of Niprisan in Nigeria. After a long search for another company, in June 2018 NIPRD signed a production agreement with Nigerian pharmaceutical company May & Baker. It is hoped that lessons have been learned and the latest attempt to make the drug readily available in local pharmacies will be successful.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox