Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation and arguably its largest economy, is in electoral crisis following the 11th hour decision by the electoral commission to postpone polls due over the weekend. It’s a good time to celebrate democracy – but also to ponder what has become of the country since it wrestled independence from colonial Britain in 1960.

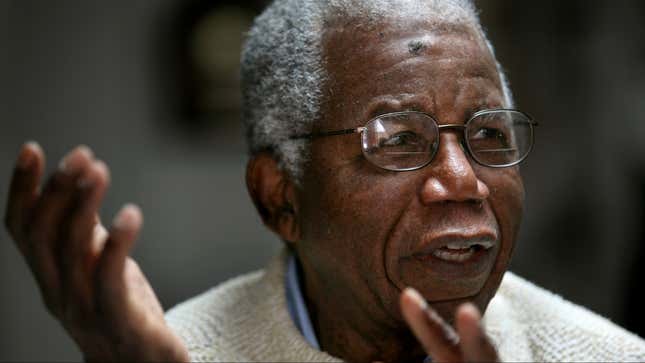

To do this, I find it helpful to consider what some of Nigeria’s most celebrated cultural icons, among them musician, commentator and activist, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti – about whose political messaging I have written—the novelist Chinua Achebe and writer and activist, Ken Saro-Wiwa, might say about their country if they were alive today.

Arguably, Nigeria has come a long way in the past few decades. There have been important, positive developments in the economy and, crucially for a nation of nearly 200 million people telecommunications. Yet it’s still racked by corruption, dreadful health and education systems, and deep immorality among some who style themselves as custodians of religion and politics.

These issues have long haunted the nation, and its cultural icons like Achebe, Fela and Saro-Wiwa were among those who highlighted Nigeria’s failings in their work.

Failure of leadership

Probably Africa’s most acclaimed novelist, Achebe, articulated Nigeria’s woes in his book, The Trouble with Nigeria. In his judgement: “The trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership.”

Few Nigerians would disagree. The country is prolific at producing leaders with questionable cognitive competence whose warped wisdom compels them to doggedly advance backwards.

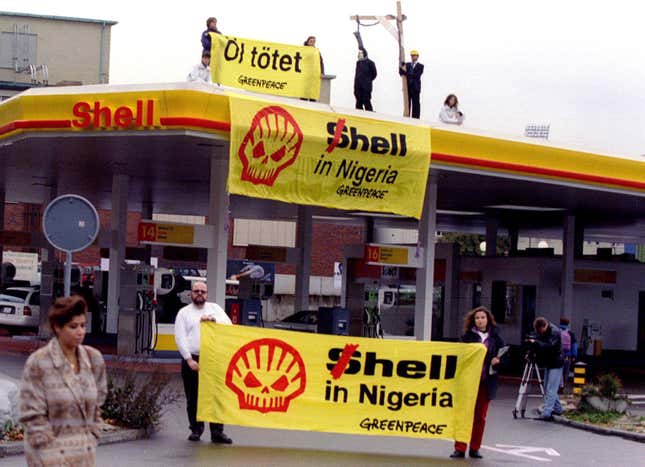

And who could forget Ken Saro-Wiwa? He was an author, television producer and environmental activist, who led a campaign against the multinational petroleum industry in his home region, the Nigerian delta, which gave rise to severe environmental damage. On 10 November 1995, he was executed by the military dictatorship of Sani Abacha, for his non-violent campaign.

I had the privilege to call him a friend and mentor when he was a contributor to Nigeria’s Vanguard newspaper where I cut my teeth as a journalist. He also wrote a book, Sozaboy, and wittingly subtitled it A Novel in Rotten English. To many Nigerians, their country is rotten. It’s like Saro-Wiwa’s unintelligible tale told in rotten vernacular by a homeless prodigal son of unknown parentage, in a moment of insobriety in an unspecified city.

What would Fela say?

But, let’s face it, the trouble with Nigeria also lies with her citizens. The late Afrobeat king, Fela Kuti, described them as “Follow Follow” people. I articulated his wise thoughts in a chapter in Music and Messaging in the African Political Arena, a recent academic book, where I wrote this:

Fela lived and died a committed political iconoclast and constant irritant to the political leadership in Nigeria… (but) Fela was not all about challenging political leadership. He also admonished his compatriots and Africans in general for being unassertive in the face of rampant systemic corruption, and not questioning their leaders’ flagrant ineptitude and bad governance.

In the lyrics of some of his songs, especially Mr Follow Follow, Zombie, Original Suffer Head, Authority Stealing, Shuffering and Shmiling, Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense, Vagabonds in Power and Sorrow, Tears and Blood, Fela was critical of Nigerians who simply look on as their leaders squander their nation’s fortunes.

Fela died in 1997. But his analysis and characterization of Follow Follow Nigerians remain pertinent. These are citizens who cast their votes for discredited politicians and routinely return them to power.

The same citizens will never support the new breed of non-billionaire leaders with the potential to wheel Nigeria out of the political and economic intensive care unit. And even in the face of old breed leaders subverting the country with corruption, nepotism and inept leadership, the same citizens opt to remain docile. They swallow their hopelessness with spiritual equanimity.

But, it’s also true that Nigeria still has men and women of vision who are imbued with the fortitude, tenacity and assertiveness to redeem their country from the “Vagabonds in Power”, as Fela labelled Nigeria’s leaders of his era.

The political messages in Fela’s songs and lyrics are constant reminders about Nigeria’s corrupt and lacklustre leadership. He was unequivocal that Nigerians could not realistically outsource the solution to their problems to the heavens. This, while they’re haplessly “Shufering and Shmiling” in some expectation of divine intervention to free them from their predicament and misery.

Nigeria, as Fela saw his country, should not be governed by political Zombie leaders forever. That was why he recommended that it was up to her citizens to rise and “do something about this nonsense.”

Uche Onyebadi, Chair of the Journalism Department, Texas Christian University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox