Fred Laryea, a grocery shop owner in Accra, the capital city of Ghana, goes from house to house with a black backpack. He talks to residents inside in the local language, Twi, earning their trust and asking very detailed questions about individuals living there and amenities available to them.

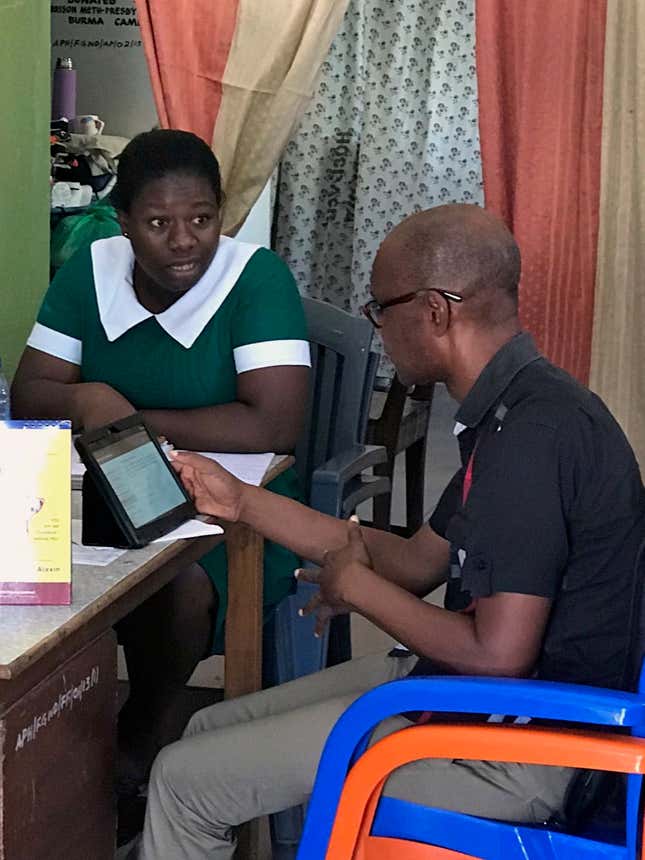

“How many people live here?” “What’s the date of birth for every one of them?” “Can you read and write?” “Do you use a private toilet?” As Laryea asks each question, he records the answer on a tablet, and then taps “next” on the touchscreen to go to the next question.

This is Laryea’s job for the week: he is one of the temporary workers hired by Ghana Statistical Services (GSS) to help carry out a trial census currently underway in a few selected districts across different regions in Ghana.

The trial is to prepare for the next decennial census in March 2020. Equipped with a tablet loaded with a digital neighborhood map, and a portable charger, field workers like Laryea are testing new technologies moving away from the pencil and paper of the previous census.

The field workers are saving and sending answers back via an app on the tablet to the central server in real time and verifying where interviewees live by GPS. Araba Forson, the deputy government statistician at GSS, say that using tablets will save the processing time down the road, as well as improve coverage and data quality.

If everything goes as planned, 2020 will be the first time Ghana uses electronic questionnaires to survey the population, a practice only a few African nations have succeeded in doing, and a lot more are trying to adopt going forward.

For a country like Ghana, where data on its residents are incomplete and infrequently updated, the census provides a rare opportunity to collect data on the people who are missed in other forms of data collection, and map every housing structure in the country. Aided by digital technologies, the census results can be useful to allocate resources and formalize much more of the country’s economy.

A clearer picture

The most important task of next year’s census is to update the population figures for all regions and districts in Ghana. The 2010 census put the Ghana’s population close to 25 million. Similar to many other countries on the continent, Ghana’s population expanded rapidly over the last decade, with a large portion of the population moving from rural to urban areas. The official population figures today for the 216 districts across ten regions are estimates based on the 2010 counts. GSS projects the country’s population to be over 31 million by 2020.

But census isn’t only about updating population figures. The categories and questions designed into the questionnaire will help collect quality data on human and household conditions across the country. The Ghanaian government wants to pack as many questions as possible in one questionnaire because the kind of desegregated data the census collects isn’t available elsewhere in Ghana.

The standard household questionnaire used for the ongoing trial census in Ghana takes about 30-45 minutes to complete, according to Laryea, with questions ranging from size of the household, basic amenities, to individual’s education and literacy levels, nationality, migration and disability status. As a comparison, the US 2020 census is expected to take 10 minutes or less to complete. The Switzerland only surveys 5% of its population for an annual census, as the nation’s database is so complete and frequently updated that it doesn’t require resource-intensive household interviews.

Ghana’s government wants to find out as much as possible about its citizens right down to how they manage their waste, what they use to clean the toilets, and how they dispose the cleaning materials. “Whether you bag it, bury it or just throw it away, we collect that information. That can help us determine how disease can spread and what has to be done to improve sanitation within the country,” says Forson.

Digital ambitions

The scale of data the census collects is crucial to the government’s effort to formalize larger parts of Ghana’s economy, where over 80% of the employed non-farming population work in informal sectors, according to the 2015 Ghana Labour survey. Jobs such as street vendors, taxi drivers or head porters, most of whom are female migrant workers from rural regions working in urban areas, aren’t registered with the government. There’s no effective way of tracking people in Ghana.

The country has tried to roll out a national identification system multiple times in the past without success. There isn’t a uniform address system, either: Many in rural areas do not have a numbered address and rely on a nearby landmark such as a tree, or a gate, to indicate where they live. The current administration wants to solve both problems: The government is pushing residents to register biometric national ID cards (Ghana cards) that assign Ghanians unique ID numbers, as well as building a formal addressing system to document all housing structures in the country since 2017. By digitizing housing structures and recording household GPS locations, the census will provide data to accelerate both processes.

A complete database of its people and buildings could help inform policy decisions on taxation and social welfare for the government: a step toward a more formalized economy. The vice president Mahamudu Bawumia noted at a dinner event last month: “To fight inequality, we must count everyone, and make everyone accountable to pay their fair share in taxes that will be used to target assistance to those who may not have had access to critical social services previously.”

The government plans to spend $84 million for the operation, according to GSS, a step-up from $54 million ten years ago. GSS, with a staff of about 300, will hire an estimate of 60,000 temporary field workers for the three weeks of census operations. Census implementation committees of all administrative levels will be formed to mobilize and educate people before March next year.

The obstacles

But even if Ghana’s strategy and ambitions are well-thought out on paper, there are still notable technical and financial obstacles to be able to deliver on these goals as planned.

In 2010, the government had to postpone the census from March to September because of a funding gap. This year, a digital census imposes new challenges: GSS currently doesn’t have the right gadgets, and the money isn’t in place yet to procure 60,000 of them.

The tablets currently being used for the trial census have to be charged every hour or so. Some new tablets Ghana hopes to acquire will be solar charged to be used in areas without electricity. They also need to be water resistant as heavy rains are expected in Ghana close to the end of March.

“If we’re lucky, we can get tablets in some other countries, then we don’t have a problem,” said Forson.

One source of the gadgets may come from countries that have conducted their censuses digitally. GSS is working with United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), a development partner for the census, targeting especially two African countries, Malawi and Kenya. Malawi conducted its first digital census last year with the support from UNFPA: among the 20,000 tablets they used, 15,000 were from the UK, while the other 5,000 were bought by the government. The Chinese company Huawei also donated a few, according to reporting from the local media. Kenya’s census is coming up later this year with a budget to procure 160,000 tablets.

“If we don’t have tablets [from other countries], the government wants us to mobilize resources to fund the gap,” said Forson. That would be other government agencies in Ghana, or the private sector. As the final questionnaire would cover a wide range of questions including nationality, sanitations and housing conditions, other agencies would be able to use the data and might be willing to help.

This reporting is supported by a press fellowship from The Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data.