August 2019 is historic, both for those with African ancestry in the diaspora, and for Africans on the continent.

It marks 400 years since the first documented enslaved Africans arrived at the Point Comfort, which is today Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. Upon their arrival on the former British colony, some 20 or so Africans were forcibly traded to colonists in exchange for food and supplies.

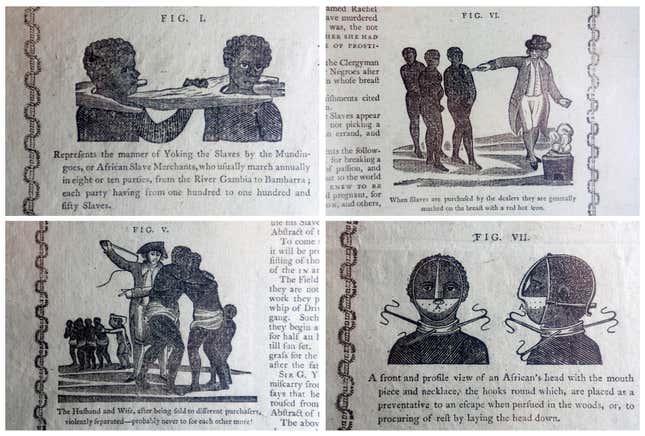

Recently, Reuters photographers visited museums in Ivory Coast, Nigeria, South Africa, and Britain to capture the global impact of the slave trade. The captivating artifacts below are a few of the illustrations and objects drawing remembrance to the brutal human toll of the practice, and its economic dominance between the 16th and 19th centuries.

The transatlantic slave trade was critical in connecting the economies of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. For the British, the journey was triangular. Slave traders bought West and Central African slaves in exchange for goods, enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas for sale, and goods produced by the slaves in the New World was shipped back to England. It was a continuing cycle, and the human horrors of the practice has been well documented.

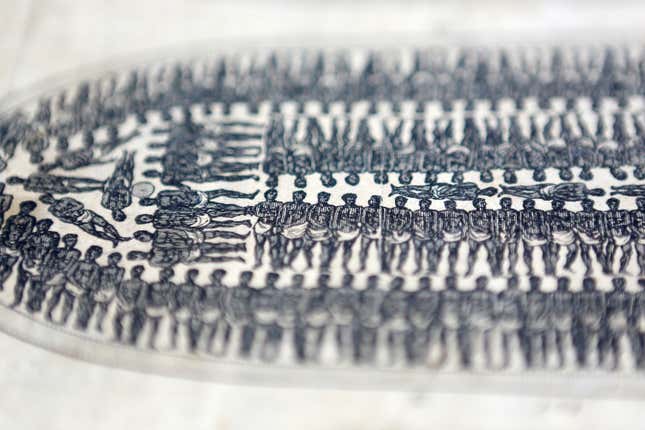

An estimated 17 million men, women, and children were snatched from their homes and shipped across the Atlantic for forced labor. A large percentage of those taken captive were young men and women of childbearing age, with elderly and otherwise disabled Africans left behind to cater to the local economies on the African coast. From those deported, nearly two million died aboard the ships, and others suffered heavily from the inhumane conditions of the crammed forced travel.

Outside of the ships, the movement of enslaved Africans was restrained, including for children. The artifacts from British museums chronicle documented instances of families being separated at slave auctions, and continued whippings in the British Caribbean plantations.

In the Cape of Southern Africa, one of the largest colonies to form modern-day South Africa, enslaved Africans from Angola, Ghana, the Indian subcontinent, and nearby African nations, including Mozambique, were imported, by the Dutch East India company, a Dutch commercial company, in the 17th and 18th centuries. Slavery soon became a dominant part of the Cape’s labor force, with slaves even outnumbering settlers in the region.

Slave importation was continually practiced for nearly 180 years, until the British occupied the colony and began to enforce a ban on external slave trading. While the practice was in place, an estimated 60,000 slaves were imported to the Cape.

For the coming 400th anniversary of enslaved Africans arriving in the US, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo has declared 2019 as “The Year of Return,” and encouraged people of African ancestry, including African-Americans, to make the “birthright journey home for the global African family.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox