After years of rapid growth in Africa we’re about to enter the age of Mobile Money 2.0

In the centre of Gauteng Province, a reluctant winter sun paints the Roodepoort sky with the day’s first semblance of warmth. Amongst lush flora in suburban utopia—Fairlands, an apt name—the gentle whirr of the heating AC quietly dominates the room. A wall of pixels is the centerpiece of attention, as a business analyst sips her coffee and closely watches the graphs.

In the centre of Gauteng Province, a reluctant winter sun paints the Roodepoort sky with the day’s first semblance of warmth. Amongst lush flora in suburban utopia—Fairlands, an apt name—the gentle whirr of the heating AC quietly dominates the room. A wall of pixels is the centerpiece of attention, as a business analyst sips her coffee and closely watches the graphs.

The city of Kampala, an hour ahead of South African time, is fast approaching the peak of mobile money usage for the day. Even a few minutes of downtime can be costly in a country where $34 million moves through an intricate digital highway every day, and you’re the one in charge of traffic control.

The MTN Group Innovation Centre is a vibrant campus in the Johannesburg metropolitan area with hundreds of invisible hands gently maneuvering the silent but tremendous beast.

In Uganda, MTN enjoys over half the market share for mobile money, enabling a generation of people to access formal financial services for the first time.

Across its 15 mobile money operating companies, MTN Group seems to dominate the African continental market for mobile financial services. Riding a strong brand and an increasing significance in the daily life of the average citizen, it is difficult to ignore the masterpiece they have built.

Making money moves

There is nowhere else in the world that moves more money on mobile phones than Sub-Saharan Africa. The region is currently responsible for an astonishing 45.6% of mobile money activity in the world—an estimate of at least $26.8 billion in transaction value in 2018 alone—this figure excludes bank operated solutions.

Mobile money operators like MTN, who also own the mobile network, typically charge in between 0.5%–3% for their various digital services, a small price to pay for the convenience.

A few thousand miles away, the last few bytes of an API call to NIBSS—the Nigerian Inter-Bank Settlement System hits a server in Lagos.

Instantly, millions of naira changes hands. It is just one transaction of thousands that day that would constitute the $21.6 billion in value that would make up the volume for June 2019 alone. Though most of it doesn’t yet come through telcos, a significant chunk of financial services in Nigeria are enabled by mobile—a national industry so far dominated by bank led innovations.

On the opposite side of the continent “Build complete” …the terminal reads, as a product manager in Nairobi gets ready to deploy the next update. 1% cash back on every ticket purchase should drive up the numbers for the weekend, just enough for her to hit her monthly target and meet the OKR for the fundraising to close.

In a country where a mobile money outage is national news, it takes more than just the basics to get customers going—no matter how exciting you think your digibank is.

This is the state of mobile financial services in Africa where the value of transactions has grown over 890% since 2011 and shows no signs of slowing down.

This incredible growth has not escaped the world’s attention, with the last few years coming with unprecedented investment into the technology sector from new and existing players alike.

At the heart of the capital war, the African consumer and the race to capture the remaining 57% of adults in Africa who still aren’t included in the formal financial system. Part clichéd buzz word, part technical descriptor, it seems the biggest names in the world can’t make enough noise about “financial inclusion.”

But how did we get here?

There is no simple answer, but in many ways the mobile phone democratised the financial services opportunity. Being a relatively recent invention, different market actors have leveraged its growing ubiquity to be able to play in a previously walled garden.

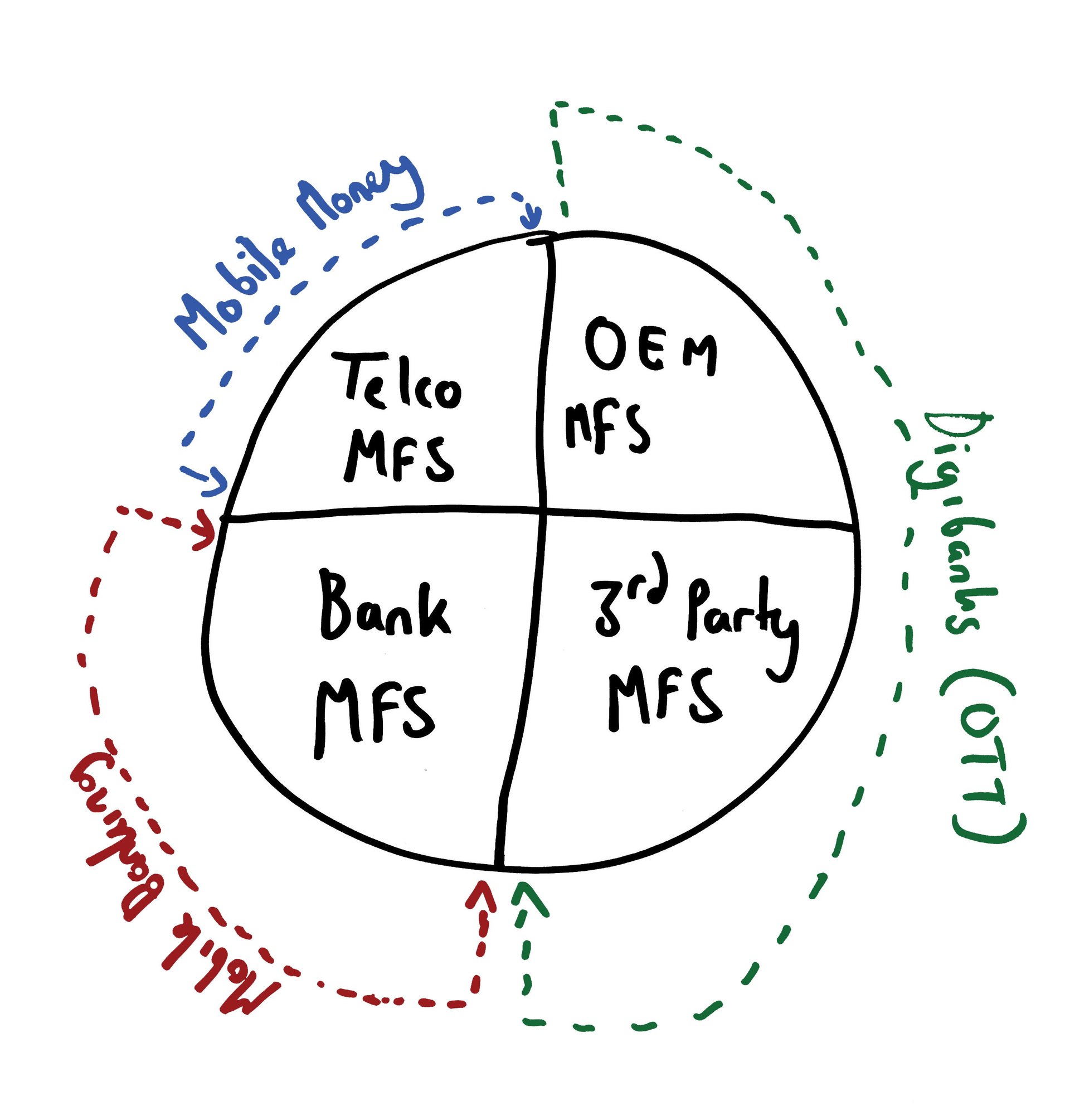

An unforeseeable convergence of technologies has leveled the technical playing field for these actors, and this article attempts to explore the various ways in which mobile financial service structures across the continent came to be, their respective strengths and weaknesses in the larger scheme of things, and what the future might look like for different approaches to banking the unbanked. Mobile money, in the classical sense, has been a mobile network operator led initiative — a service that comes built-in to your SIM card and available to activate at the very moment that you get your line from the operator.

Unsurprisingly, Safaricom M-Pesa is the most widely cited example of such a mobile money deployment that has been successful at scale, and deservedly so. The Central Bank of Kenya 2018 statistics indicate that over 40 million people moved $38.3 billion on Kenya’s mobile financial rails, a significant chunk of which is M-Pesa. Such large volume is only possible through the scale that is native to network level solutions that are owned by telecom operators and sold to banks and MFIs.

What is Mobile Money 1.0?

By running the mobile money software on the core mobile network, you ensure the service is compatible with all phones on your network without the need for the user to install anything else or connect to the internet to use the service. This works well for targeting the widest possible range of users, and allows organic discovery and activation of the service backed by local marketing campaigns. This has been the formula that has led to the success of M-Pesa and every other telco-led mobile financial service over the past decade.

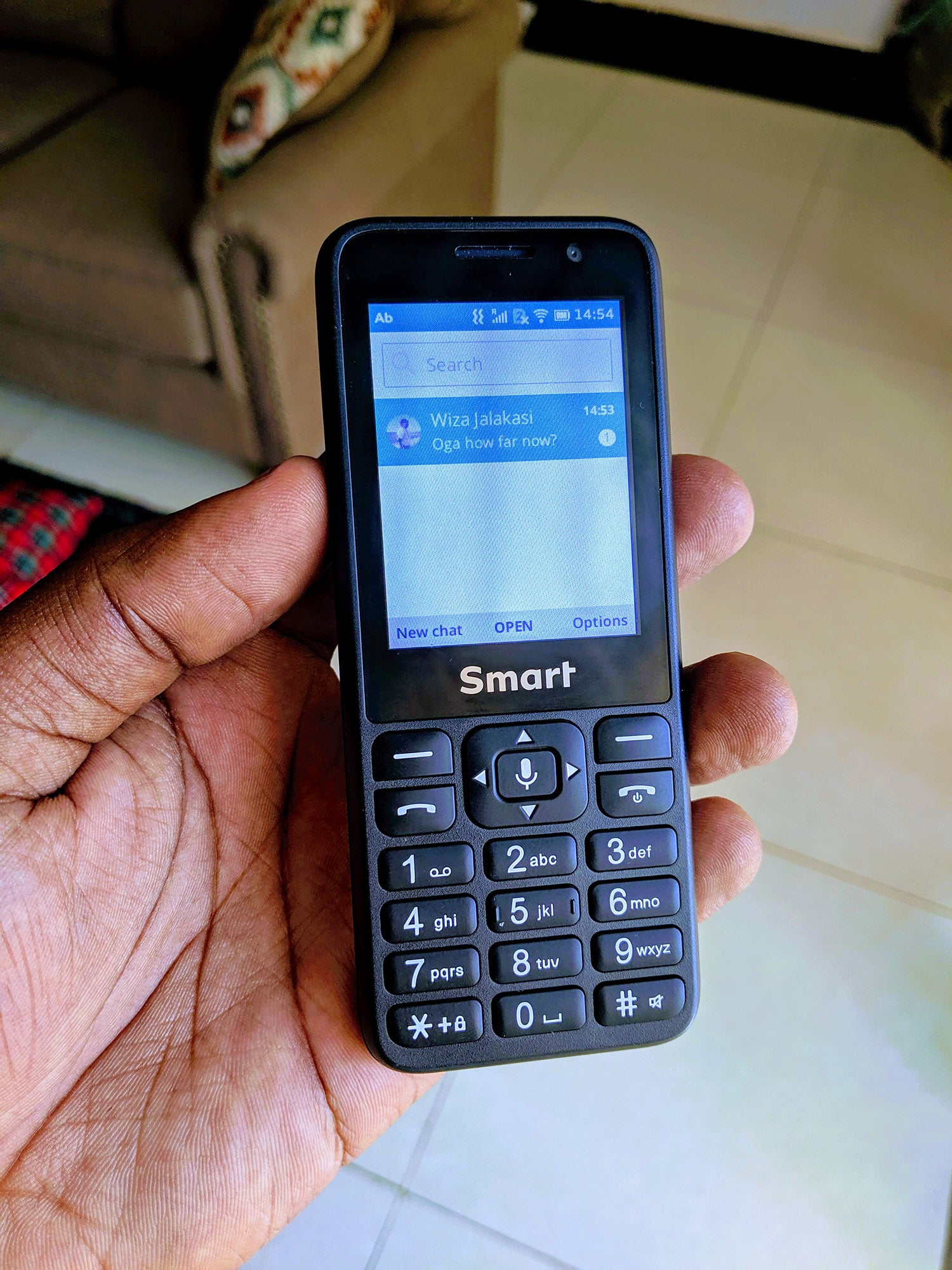

This is Mobile Money 1.0—digital wallets operated via a text interaction driven interface that is powered by either USSD or SIM toolkit technology — present on all devices as part of the GSM standard but not very intuitive.

Telcos have perfected the art of running these, with over 270 deployments present in the world today. They represent the first iteration of mobile money services and kickstarted the revolution, practically inventing mobile financial services as we know them today.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, we now see for the first time an industry wide trend with more launches of challenger bank apps, affectionately referred to as digibanks for the rest of this post. These types of apps represent the first iterations of Mobile Money 2.0.

Digibanks, almost exclusively running on smartphone platforms Android and iOS, provide a much more refined and enhanced user experience—with specific features that are compelling to a more sophisticated user. A sophisticated user has needs that are beyond having a place to receive, store and send money.

In the initial years of their conception, digibanks were dismissed by industry incumbents. Relatively low smartphone penetration, coupled with slow adoption and regulatory challenges made these to appear like luxury apps for a sophisticated niche at best and not institutions challenging the relevance of banks as we know them today.

Digibanks in Europe such as Monzo and N26 have been amongst first generation players to really take off, validating the market opportunity for retail banking amongst the world’s increasingly digitally native population.

To name a few, African digibanks like Zazu, Kuda, Carbon and several others have prepared war-chests in the millions this year to explore the space.

Last year, over half of all investment into technology startups in Africa was directed at fintech innovations.

The United States is finally seeing a mobile payments ecosystem pick up with players like Venmo and more recently, Cash App, exhibiting incredible growth. (Sidebar: Welcome to the club, we had been waiting for you guys to catch up ;)

Simultaneously, the average cost of smartphones is still decreasing and more units are being shipped to the continent each year.

A few weeks ago, Shenzen Transsion Holdings, owners of the Tecno, Infinix, iTel and Oriamo brands of mobile devices announced the launch of the first ever Tecno device running KaiOS—a challenger operating system — now third after Google’s Android and Apple’s iOS— with the capability to run apps that were only previously restricted to the two major operating systems.

Why is this important?

The cost of these devices tends to be under $25—making them affordable for first time Internet users who are migrating to consume online services like WhatsApp to stay connected in a globalized world and bypass telco messaging costs.

KaiOS has already seen incredible success with this approach with the launch of the Reliance Jio phone in India—converting tens of millions from 2G feature phone users to Internet-enabled 4G users.

Transsion dominates the mobile phone market in Africa.

The China distribution structure is unparalleled across the continent and they are uniquely positioned to potentially accelerate the rate of new mobile internet connections in Africa faster than ever before.

The extensibility of KaiOS is also a compelling value proposition to developers of digibanks as they can now for the first time build smart interfaces and interactions for the unsophisticated user.

KaiOS is backed by investment from Orange Digital Ventures and has a partnership with MTN with devices already in the market. This means that two of the three largest mobile network operators on the continent have already placed their bet that the operating system will take off.

It is not difficult to imagine a future where the next few million devices shipped to the continent are predominantly low cost Android and KaiOS phones.

Rocky road

It’s not all sunshine and daisies for digibanks in Africa. Despite the increased investment and and growing market to engage, the biggest challenge for them still lies ahead.

An instrumental component of any mobile financial service are the various places at which users can convert their cash into your mobile value store (on-ramps) and liquidate it to cash (off ramps). Telcos have solved this brilliantly by setting up agency networks — a system of physical points frequently distributed and typically operated by informal retailers.

Safaricom M-Pesa has over 160,000 agents and is able to effectively operate their mobile financial service from end to end without relying on any third party.

Almost all digibanks don’t have agency networks — which are nightmarishly expensive to setup and can take years to become effective, and are not at all positioned to begin setting up their own now. Subsequently, they are forced to rely on existing mobile financial services to power on-ramps and off-ramps for their own wallets — the very same services they are trying to disintermediate. Some digibanks have opted to go the route of charging user debit and credit cards to fund their wallets — a potentially better option but limited in scale as card penetration is only significant in South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt and the few other African countries that have adopted them.

Further still, the transaction charges incurred by digibanks because of using third party rails makes it difficult for them to monetize their services, as marking up that cost would simply reduce the incentive for users to consider their service.

The question though is:

Why would I use another app to send money and receive money in Kenya when M-Pesa works and I’d have to use M-Pesa to cash into your app’s wallet anyway?

Digibanks have responded to this challenge with some clever value propositions, including discounted airtime top-ups, special deals on goods and services and my personal favorite, international remittances—a good example of such is Chipper Cash—and it seems to be working well so far.

Apart from developers and startups building digibanks from the ground up, it would be irresponsible to not carefully consider the significance of incumbent banks and other third parties breaking into the market.

These potentially pose a more significant threat to telco-led mobile money solutions because these established players tend to already have distribution and the muscle to promote their solutions effectively.

The success or failure of such initiatives is yet to be seen but telcos would be wise to be wary of such players. The last time telcos failed to respond to an over the top (OTT) threat, WhatsApp happened.

One of the most relevant OTT threats lies with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) foraying into the space. Companies like Transsnet Financial, the financial services subsidiary of Transsion Holdings have been quietly setting up international structures to allow them to effectively complete in the mobile financial services vertical.

Their digibank app, PalmPay, launched recently in Ghana and Nigeria and is already in the top 10 free finance apps in the Google Play store charts for Android in both markets.

The reason OEM digibanks are particularly concerning for telcos, is because the OEM can preload their application on every device that they ship to the market.

This, combined with deliberate efforts to get first time users to try it could enable OEM digibanks to grow faster than all others by simply being the default. Transsion has managed to do this before for music services with Boomplay, which has seen it break 50 million “active” users to be the largest music streaming app in Africa. Its success has been because most users find the app preinstalled on their phone and started using it because it was there.

The power of defaults has played well in their favor and is an obvious strategic advantage. The network effect is a huge driver of adoption of new technologies, and in this way OEM digibanks could potentially scale faster than other players.

Further still, Transsion filed for an IPO at the end of September, with a significant chunk of it earmarked for R&D and diversifying revenue streams—digital payments being cited as part of it. A quick glance at the Terms and Conditions of PalmPay Nigeria reveals thirteen mentions of the word “agent”, alluding to the possibility that PalmPay will set up it’s own agency network to eliminate any dependency on existing mobile finance or card rails.

Similarly, a now revoked LinkedIn job post shows that KaiOS, now effectively a “software OEM” will make some foray into the payments space. It is unclear from the job post whether the product would store value or just process transactions on behalf of merchants and other providers.

Power of incumbency

Naturally, the incumbent banking industry refuses to be left behind. The first wave of digibank offerings from incumbent banks is already well under way. Standard Bank has taken an interesting approach by investing into a 9-year old fintech, Nomanini, for instance.

CBA Loop, recently launched in Kenya offers an all-digital banking experience with the only in-store visit being for the sake of fingerprinting for KYC and to collect an International debit Mastercard.

Before we continue, it’s very important to distinguish between native digital banking and online banking.

Many deployments of the latter already exist—this is where your bank might give you a website or app with login credentials to access your existing bank account and manage transactions.

The former is a purely digital experience, where everything from account opening to funding the account takes place on your device. CBA Loop still depends on existing mobile financial services — most commonly, M-Pesa, to work. They do have the option of depositing via any CBA Branch and various agency options as well.

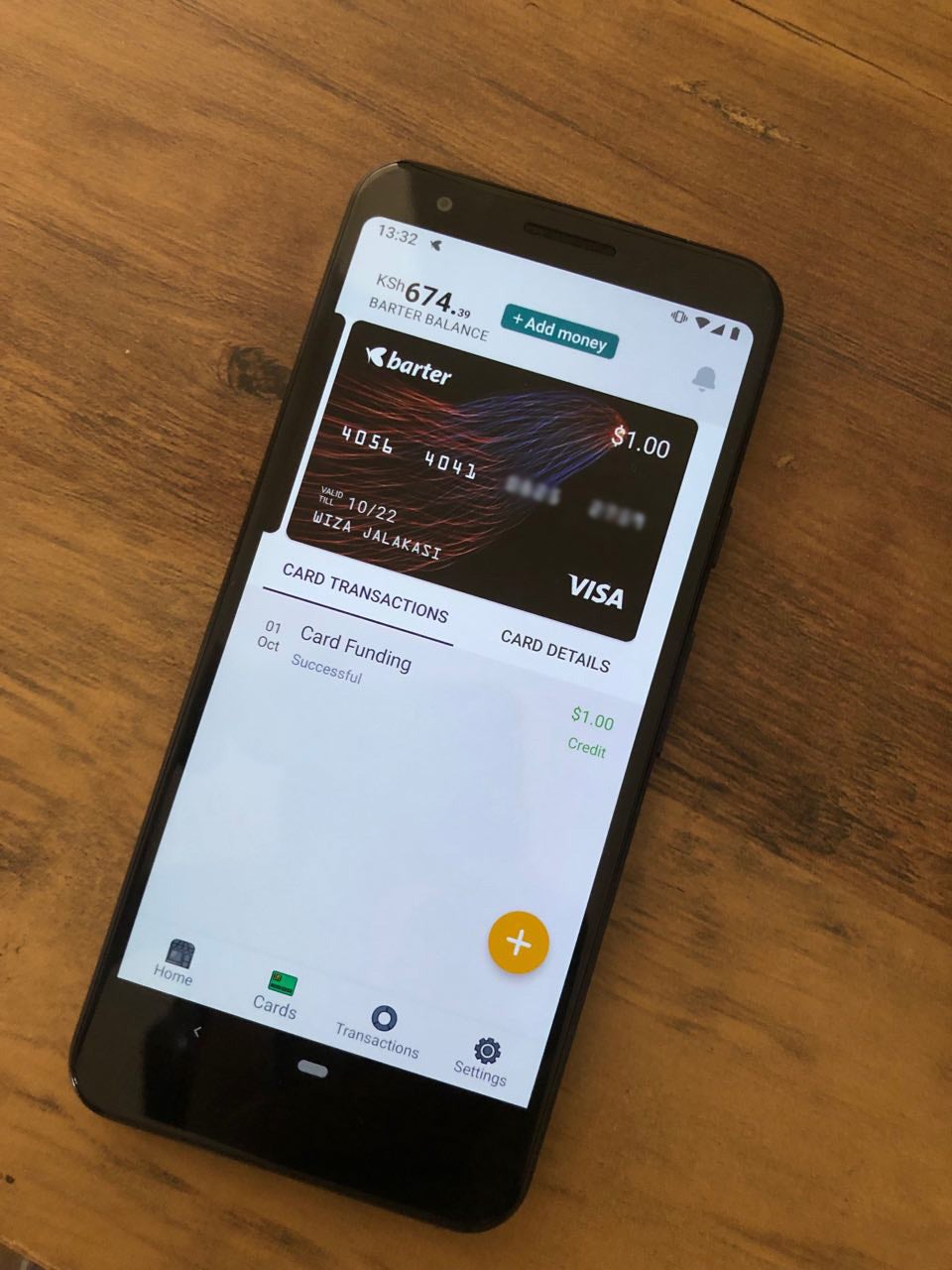

The biggest differentiator between CBA Loop and all of the dozens of digibanks I have studied on the continent is that they are the first and so far only ones offering a physical card for transactions.

Some players, like Flutterwave Barter, offer a virtual Visa card with a US address that works great for region-restricted services like Spotify but these tend to fall short in utility when you need to pay at a point of sale or withdraw cash from an ATM.

All of these various innovations led by actors across different verticals of the financial sector have led to a convergence of technologies that now make it difficult to differentiate between various types of mobile financial services.

The age of Mobile Money 2.0

What used to be defined as mobile banking, mobile money, USSD based banking et al, will soon be bucketed into one general descriptor in the age of Mobile Money 2.0.

To better prepare for this future, we must understand the attributes that characterize Mobile Money 2.0. My presentation of these characteristics is not at all comprehensive or definitive as there is currently no authority that globally defines standards for what mobile money is.

With that in mind, any ideal Mobile Money 2.0 solution should have at least:

- A refined, graphical user interface and intuitive experience

- Mechanisms to liquidate value stored or transfer to other forms of digital value

- Utility beyond peer-to-peer and merchant transactions

- Extensibility for services to easily integrate with it

It’s worth noting that some mobile money 1.0 deployments already have some or all the above characteristics — MTN Uganda for example, has all this present via their MTN app (Mobile M oney 2.0) but no graphical experience on their USSD implementation (mobile money 1.0).

Under this logic, then one may argue that the key differentiator for Mobile Money 2.0 lies primarily in the quality of the interface and I believe this to be true.

The interface in this sense refers to:

“The big thing in the 2.0 iteration is the endless opportunity to build additional services on top of mobile money as well as the endless additional opportunities to monetize those services. That’s enabled because you’re moving the brain of the transaction up the stack into the smartphone instead of the network” —Marcello Schermer, Head of Expansion at Yoco

Despite it’s ubiquity, USSD as a user interface is far from ideal and introduces quite a bit of friction in the adoption process as first-time USSD users learn how it works. This, coupled with a time-out window in which a transaction must complete, has limited its usability to a subset of users who have the patience to learn.

By providing a graphical interface, Mobile Money 2.0 will become potentially appealing to all users who are exposed to it. It would be far from the first time that simplifying an interface would drive adoption. Famously, Windows 95 became the most popular desktop operating system in the world by implementing a graphical interface and making PCs fun and easy to use for first time users.

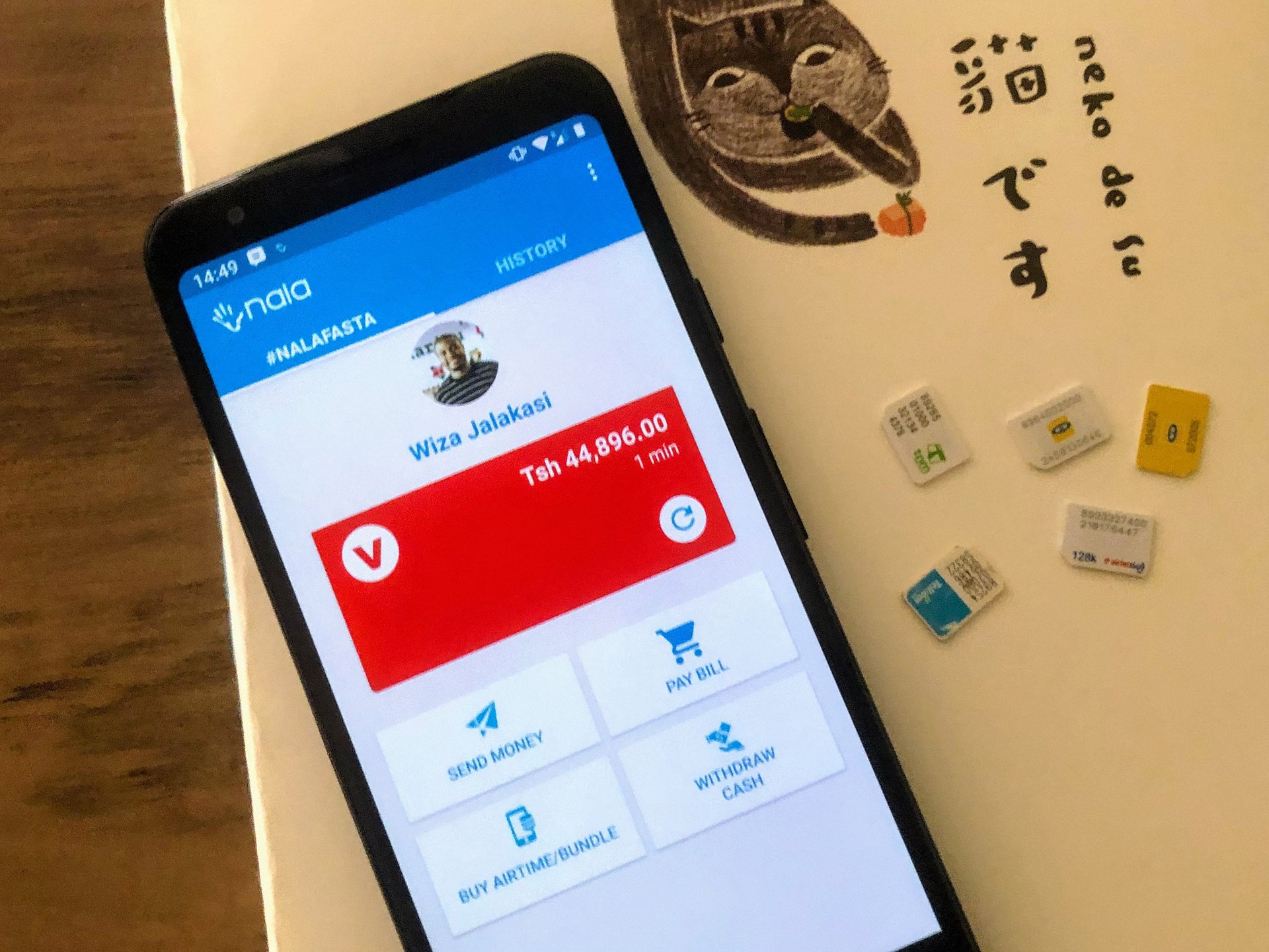

This is already taking place in Africa with apps like NALA, FayaPay and Alcor already cumulatively boasting hundreds of thousands of users.

These type of apps are particularly different from other third party digibanks in that they do not attempt to store value or bypass existing mobile financial services in an OTT fashion.

Instead, they simply provide the interface layer for managing various types of mobile financial services. This is something no individual MFS provider could ever do without effectively promoting competing brands, so it seems that there may always be room for a neutral intermediary to aggregate multiple wallets.

The reward for such an intermediary? A rich understanding of user transaction history and behavioral patterns that could be leveraged in interesting ways to create more value.

However, to have value stored across purely digital planes is only the beginning of what is possible in an increasingly mobile accelerated world.

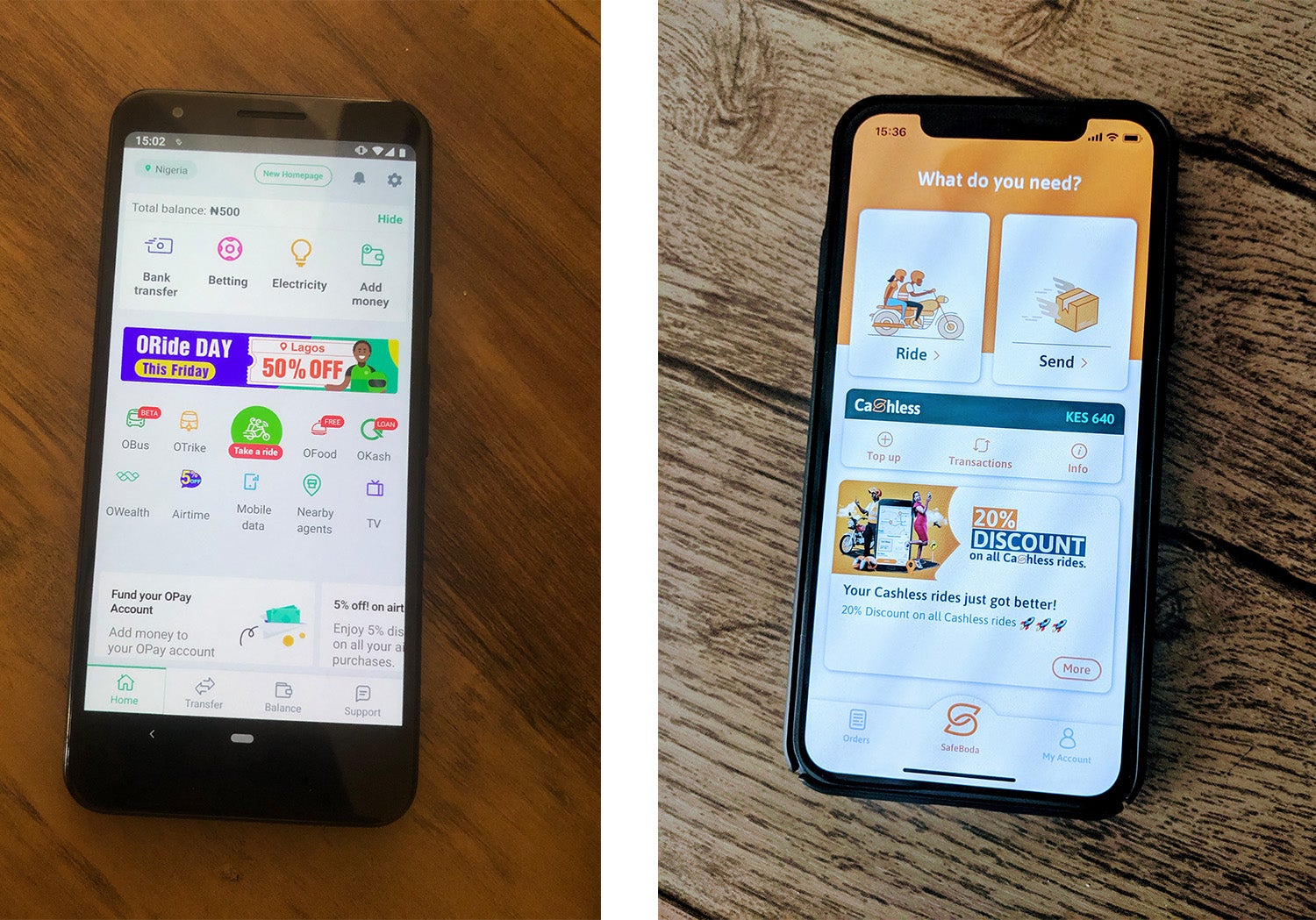

Players such as OPay in Nigeria and SafeBoda Cashless in Uganda have so far managed to capture a significant amount of value within their respective stores and are seeking new ways to increase it’s utility in an apparent bid to become superapps — platforms that combine various services into one. This approach has worked wonders in China, Indonesia and other Asian markets.

By layering additional services that can only be purchased with their respective value stores, they effectively increase the utility and therefore perceived value of their mobile financial service despite the nominal currency value being the same.

This approach is often criticized as it sometimes requires the sale of said additional services at a price below the unit cost of providing them—leading to heavy losses if sustained for too long.

The idea is to create a dominant mobile financial service that is widely trusted and then can be made profitable through economies of scale.

Ultimately, it remains to be seen which of the approaches to building Mobile Money 2.0 will succeed at scale—if any one approach can even succeed at all. Africa’s highly fragmented regulatory landscape is a massive barrier to growth for startups and incumbents alike, with the cost of license acquisitions easily reaching millions of dollars.

Nigeria seems to be amongst the few countries with highly progressive regulation and structures that enable fintech innovation. The burden of KYC for startups is easily alleviated through use of the BVN—a digital identifier for Nigerian residents to easily access financial services.

Further still, progressive incumbent banks like Providus Bank accelerate innovation by providing virtual bank accounts and wallets to fintechs in the space.

Perhaps then, different approaches will see success or failure as a factor of the environments that they operate in.

Perhaps not, as the world of technology has proven itself to be amongst the most unpredictable of trends.

This article was originally published on Medium and was republished with permission.