Accenture executive Rui Trigo Guedes didn’t react as you might expect when, in 2016, a top newspaper compiled corruption allegations against one of his firm’s clients, Isabel dos Santos, Africa’s first female billionaire and daughter of Angola’s autocratic then-president.

In the previous five years, the global consulting giant had done work valued as high as $54 million for three ventures in which dos Santos had either a minority or a controlling stake, according to leaked files seen by Quartz. But instead of expressing horror at discovering his company may have helped legitimize and enrich an alleged kleptocrat, Trigo Guedes, then an executive director in Accenture’s Portugal office, appeared to shrug it off.

He wrote to one of dos Santos’ top money-men about the journalist who presented the video. “Read this to understand Pedro’s world,” he wrote, referring to Pedro Santos Guerreiro, then editor-in-chief of Expresso, the Portuguese newspaper that published the allegations.

Trigo Guedes forgot to attach the suggested reading. But his correspondent, a senior executive at Fidequity, a dos Santos-owned management services firm that plays a central role in her business empire, similarly made light of the allegations. “Expresso has always liked to beat up on us,” he wrote back.

Trigo Guedes was likely already familiar with the allegations. Forbes published a damning report on her riches in 2013, and accusations that dos Santos’ wealth originated from government handouts were widely known. In late 2015, a few months before he sent the email, Transparency International named dos Santos one of the 15 most potent symbols of corruption in the world.

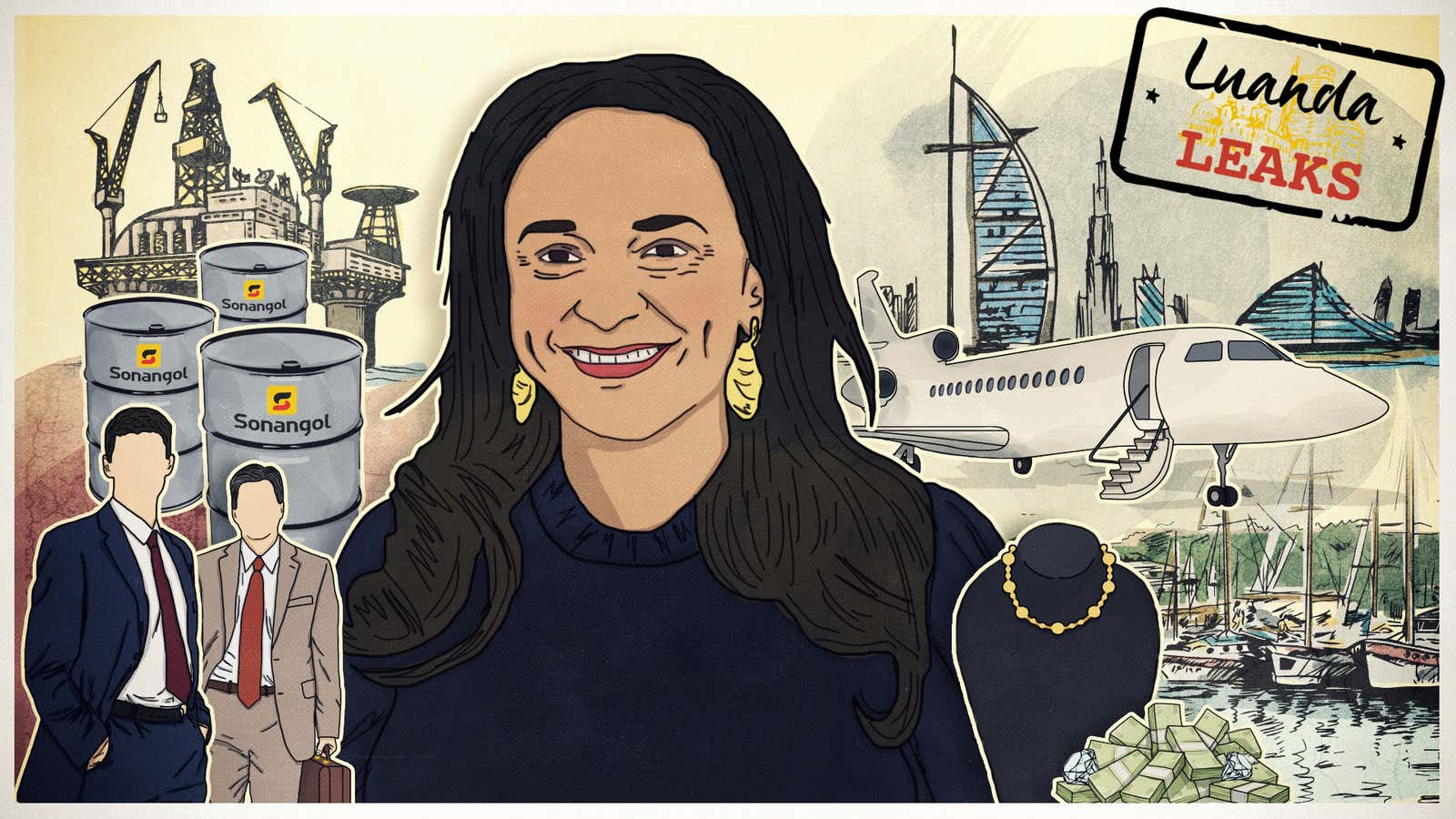

The exchange was found in the Luanda Leaks, a trove of more than 700,000 leaked emails, contracts, and other documents. More than 120 journalists in 20 countries spent more than eight months combing through the files, which reveal how dos Santos siphoned hundreds of millions of dollars in public money out of one of the world’s poorest countries. Meanwhile, a cohort of Western consultants and accountants profited from her empire, and helped legitimize it. The Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa, a Paris-based advocacy and legal group, first passed the leaked files to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). ICIJ then shared the files with reporters from 36 news organizations, including Quartz and Expresso.

Quartz members support high-quality, investigative journalism like this in a time when we need it most. Become a member and help build the future of Quartz.

Dos Santos has denied any wrongdoing. She said the leak was part of a “concerted attack” on her by the Angolan government. “[They] have decided to go and hack my offices, leak certain documents to investigative journalists, and then to put these questions forward,” she told the BBC, a Luanda Leaks partner.

The leaked files don’t indicate that Accenture broke any laws in its work for dos Santos-tied companies. But they do reveal Accenture to be part of a system in which dos Santos rerouted her money into businesses tied to the West and hired well-reputed consultancies that gave a stamp of legitimacy to her empire.

Professional services firms like Accenture “are part of a system of finding the safest landing for all the assets that are siphoned off,” Ana Gomes, a Portuguese diplomat and former member of the European parliament told the New York Times, a Luanda Leaks partner.

Dos Santos herself has pointed to these relationships as evidence of her legitimacy. In October, she said she had passed careful vetting to work with firms including “consultants who are in the top five worldwide.”

Accenture declined to answer questions on this story, saying it doesn’t comment on the specifics of its work for clients. Trigo Guedes, who no longer works for Accenture, didn’t respond to several requests for comment.

The road banks wouldn’t travel by

Between 2012 and 2014, dos Santos and her husband became toxic to Western banks, which are much more tightly regulated than consultancies like Accenture. The leaked files show that giants like Citigroup, Barclays, Santander, and Deutsche Bank all refused to work with dos Santos or her husband, Congolese-Danish businessman Sindika Dokolo. “These guys hear about Isabel and they run like the devil from the cross,” a dos Santos employee wrote to a colleague after the Santander rejection in 2014.

Consultancies and accounting firms, however, maintained lucrative relationships with dos Santos and her empire. All the Big Four accounting firms continued to work for companies in her empire, even after the allegations of corruption were made public, as did consultancies like McKinsey & Company and Boston Consulting Group.

The banks’ refusal to work for dos Santos should have been “a red flag that cannot be ignored,” said Michael Hershman, a co-founder of Transparency International and CEO of the Fairfax Group, a compliance consultancy. He acknowledged it was “difficult but not impossible to find out” that banks had rejected companies tied to the couple.

“It’s part of the due diligence process, knowing who the banking relationships are with. If the banking relationships are not with a major financial institution and you’re dealing with a multinational customer, you wonder why,” Hershman said.

“You always have to be concerned about the origin of the money you’re going to be receiving—is it part of the fruit of the poisonous tree?” he said. “If the money was originally accumulated through corrupt acts or illegal acts, any income or revenue generated from those acts—regardless of how far down the line—is tainted.”

But, unlike banks, consulting firms are mostly unregulated, meaning reputational risk is often the biggest consideration when debating whether to take on a client. For Accenture, that risk is more tangible than for other big consultancies, since it is a public company and bad news can hurt share prices, Hershman said. Accenture itself also provides advice on so-called Know Your Customer and anti-money-laundering compliance.

Angolan red flags

Accenture’s ties with the dos Santos empire date back to 2010, when it began work for an exploration joint venture between Angolan state oil company Sonangol, Italian state energy firm Eni, Portuguese energy company Galp, and Exem Holding, a Dutch-based company owned by Dokolo, dos Santos’ husband. He also owned a minority stake in Galp, held through Exem.

Exem invested $36.6 million in the project between 2008 and 2014, according to the leaked documents, but seemingly failed to answer cash calls for a further $9.2 million between 2012 and 2015. Accenture prepared drilling reports, budget documents, and meeting minutes for the venture. Its work for the joint venture was valued at about $4 million and continued until 2014, internal documents show.

While Dokolo owned Exem on paper, emails found in the Luanda Leaks files suggest dos Santos injected funds into the company and played a role in green-lighting its operations, but that her aides may have tried to obscure her involvement. A public document (pdf, p.3) published by Portugal’s Competition Authority in 2012 says dos Santos owns a stake in Esperaza, whose shareholders are Exem and Sonangol.

Dos Santos’ husband’s stake in Exem was first reported by anti-corruption nonprofit Global Witness in March 2010. The first mention in the leaked files of Accenture’s work for the joint venture dates to the same month. In 2012, a Citigroup subsidiary walked away from a financing deal with a company whose shareholders included Sonangol and dos Santos’ husband, who held his stake via Exem. The next year, Barclays gave the same reason for canceling a similar deal the night before its planned announcement.

Accenture’s compliance team should have been “very wary” about the project, said Daniel Garen, the principal at Pivot Point Compliance Management and a former counsel for Siemens’ medical technology arm and the American Red Cross, who noted he couldn’t be definitive without seeing Accenture’s due diligence reports.

“Oil and gas is one of those areas that is known to be rife with issues,” he said. “You have an industry that is problematic, a country that is problematic, someone who’s connected to the government who’s problematic, an article in the mainstream press that purports to show there’s corruption. That is a lot of flags to clear.” Asked how often a case with that many flags is cleared, he said, “Extremely rarely.” Clearing them would mean having a lot of controls in place to monitor dos Santos’ role, but even then it would be difficult, Garen said.

The Forbes article, which reported that dos Santos’ “fingerprints are everywhere” on Exem, didn’t appear until 2013, but Garen said good compliance involves regular media monitoring and an annual check on the client. Contracts should have provisions that allow termination for a compliance violation—which doesn’t necessarily involve conviction under the law, he said.

Accenture, headquartered in Ireland, was also hired in 2015 by Contidis, the company behind an Angolan hypermarket network majority-owned by dos Santos and her husband. Its job was to license and implement SAP, a widely used business software. (SAP, a German company, was paid $135,730 by Contidis.)

A draft statement of work presented to Contidis suggests that Accenture’s international office signed off on its Angolan branch’s work. The document noted it was awaiting approval from the “Accenture international structure.” The annual license for the software cost about $650,000 (a 40% discount, files show), and Accenture’s work on implementing the software between 2015 and 2016 was valued at $5.9 million, internal files show.

In a statement, SAP said it is “committed to the highest standards” of ethics. “Our policy is, and always will be, to carry out all company activities in accordance with the letter and spirit of applicable laws in the more than 180 countries in which we operate,” the company said.

Portuguese pals

In Portugal, Accenture has done lucrative work for telecom giant NOS (then named ZON), starting in 2011. Dos Santos first invested in the company in 2010, became its largest shareholder and joined the board in 2012, and in 2013, a firm she co-owned became ZON’s controlling shareholder. Internal files suggest Accenture earned up to $43.5 million between 2011 and 2014 for overhauling the company’s IT system. A 2015 budgeting document suggests Accenture would be paid $6.8 million per year between 2015 and 2017.

While Accenture enjoyed its relationship with companies owned or part-owned by dos Santos, the firm’s senior Portuguese executive, Trigo Guedes, developed a friendly relationship with one of dos Santos’ own executives. After enjoying a “great night” in November 2015, the two met up for dinners and lunches, discussed a “top” gin from Porto, and Trigo Guedes tried to get tickets from corporate partners to see a Bruce Springsteen concert together, according to leaked emails.

Trigo Guedes furnished his friend with news articles and research about Angola and dos Santos. He shared one report by research firm IHS that discusses possible succession scenarios after dos Santos’ father, Jose Eduardo dos Santos, steps down, and describes her appointment as chair of state-owned Sonangol as, “a controversial decision that underlines our view that ultimately political rather than commercial considerations will guide the oil-sector restructuring process.”

As for his email about the journalist behind the Expresso piece, Hershman, the anti-corruption expert, said: “If you’re a golfer that’s one you want to ‘mulligan’—‘Let me do it over. Let me take back what I’ve said.”