One of my earliest memories is of violence and death. It happened in Harare in 1984 when I was about seven years old. I was supposed to meet a friend to play at a dump site together. He got there before me and started playing with what turned out to be a hand grenade.

The bomb exploded in his hands. He died.

I was lucky to survive but I have no doubt that the incident shaped who I was to become.

The device, from my understanding now, had been left by either Rhodesian soldiers or guerrilla fighters during the war of liberation which raged between 1966 and 1979. Death from grenades and landmines was commonplace in Zimbabwe during and after the struggle against colonial rule.

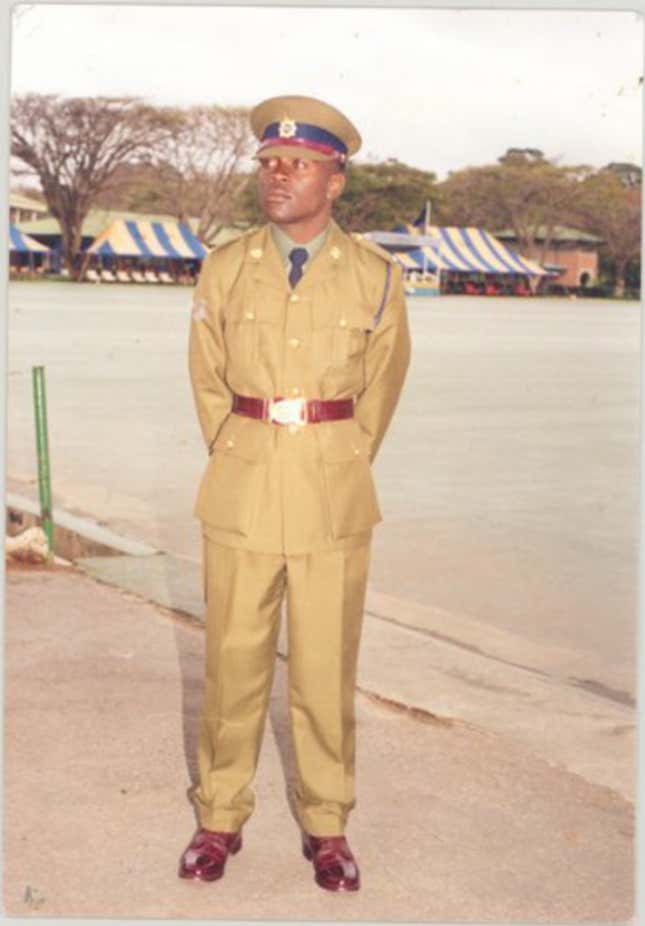

My next exposure to serious violence came when I joined the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) as a constable in 1998. I was trained by former liberation war fighters and soldiers whom we suspected had been redeployed from the notorious “5th Brigade”. This army unit was responsible for the murder of thousands of Ndebele-speaking people and supporters of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union in the 1980s. I joined the police partly due to the lack of employment opportunities and the influence from my stepfather who was a police sergeant.

The police trainers would subject recruits like me to various forms of torture, including water boarding, and battering the soles of our feet with rifle butts and sticks. There were other “endurance exercises” that went way over the top. For example, recruits would be ordered to lie down and forced to roll over repeatedly until we were dizzy and throwing up. Apparently, this was done to strengthen us—both physically and mentally—and to get rid of “civilian weaknesses”, as one trainer put it. I spent most of my post probation period with the Police Protection Unit, the agency responsible for the protection of prominent state ministers, judges, and other VIPs.

But I only really began to realize the extent of the systemic violence in my home country when I left Zimbabwe and started looking up texts, documentaries, and meeting surviving victims of atrocities. In the last 50 years, five main conflicts have taken place in Zimbabwe. The liberation war (1966-1979), political violence (1980-present day) and the Matabeleland democides (1981-1987)—this is also known as Gukurahundi which is a Shona word meaning “early rain that washes the spring chaff”.

Finally there were the violent farm invasions and the Marange diamond massacre. Hundreds of thousands of people who were caught up in these conflicts have been killed and gone missing—their deaths covered up and brushed under the carpet by the state.

By 2005 I had joined the police in the UK. But despite my new life I couldn’t stop thinking about how, when, and where people were being kidnapped, killed, and concealed back home. This had a profound influence on what I chose to do with the next chapter of my life in academia and research. I enrolled for a degree in Forensics and Criminology, pursued a master’s degree in Crime Scene Investigation and then a PhD in Forensic Archaeology.

My research has brought me full circle and taken me back to those dangerous playgrounds which I drifted in and out of as a child. I wanted to use my skills as a forensic investigator to find the secret mass graves, the clandestine burial spots. I wanted to know where “the missing” were being hidden. I realized that no systematic forensic investigation of that kind had ever been undertaken.

I was interested in forensic identification, exhumation, and the cultural aspects of burial. I interviewed over 60 witnesses—including current and former MPs, human rights defenders, and victim family members. I had to keep the identity of my witnesses a secret to protect them, as many were in fear of their lives. Speaking out can be fatal in Zimbabwe.

Some of what I discovered during my journey was startling. The sheer scale of the killing was shocking—so were the methods of torture. Some burial locations seemed to be selected at random, some were opportunistic interment while others took forethought and planning. The burial methods were dependent on which arm of the state had done the killing and when. Despite this, my research was able to uncover the tactics used by the state to hide thousands of bodies. Tactics including, stacking multiple bodies on top of each other at cemeteries, dumping bodies in mortuaries, and burying them in forests, near schools, hospitals, and in disused mine shafts.

‘Fallen heroes’

I discovered—mainly through witness testimony—that the Fallen Heroes Trust (FHT), which is aligned to the ZANU-PF government, has been on the forefront of dubious exhumation and identification practices since the early 1980s. It used approaches which made it almost impossible to find anyone accountable for the deaths. The Monkey William Mine exhumation of over 600 human remains in Chibondo is one such example. Here, standard anthropological identification methods where ignored. And when human remains are discovered, state propaganda machinery goes into overdrive.

Supporters of then president Robert Mugabe claimed the bodies were those of people killed between 1966 and 1979 under the regime of former president Ian Smith—the last white prime minister of the former colony of Rhodesia. Forensic tests and DNA analysis were not carried out. Instead, Saviour Kasukuwere, a government minister at the time, told the media that traditional African religious figures would perform rites to invoke spirits to identify the dead.

Mr Kasukuwere, who is now in exile, said the Chibondo remains were discovered in 2008 by a gold panner who crawled into the shaft. But spirits of war dead had long “possessed” villagers and children in the district. He said: “The spirits have refused to lie still. They want the world to see what Smith did to our people.”

I spoke to an anthropologist who attended the exhumation as an observer who told me that some of the bodies were wearing contemporary clothing which did not exist during the liberation war. Amnesty International advised the government to halt exhumation, pending forensic investigation. But this advice was ignored.

My research also found that the state of the human remains in Chibondo pointed to the presence of lipids, blood, and decaying flesh. It is highly likely that these bodies are the remains of supporters of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) and former Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) cadres. Since its formation in 1999 hundreds of supporters have been killed, injured, or disappeared.

The FHT routinely exhumes remains without following accepted and professional forensic approaches. For example, black humus soil was incorrectly attributed to human remains found at an exhumation at Castle Kopje farm in Rusape according to one witness I spoke to. During a different exhumation, another witness told me: “One member of the FHT picked up a walking stick and assigned the remains to the individual next to it.” No other identification was used to ascertain identity, according to my witness.

The FHT also claims to have exhumed over 6,000 bodies around the country using “spirit mediums”—who are seemingly deemed more effective than forensic science.

‘Blood soaked human remains’

One witness I spoke to described how they were detained at Bhalagwe Camp, which is south of Bulawayo where the 5th Brigade set up a concentration camp in 1985. The source, aged only 14 at the time, witnessed a daily routine of dead bodies being dumped into the disused Antelope mine shafts five kilometers away. They were dumped in the old gold mine after they had been tortured and killed in the camp. The man, now in his 50s, told me, “I used to be selected, often to assist in dragging blood soaked human remains from the campsite to be deposited into toilet latrines or transported into nearby disused mine shafts.”

Another male victim I interviewed recalled how he was seized from a bus traveling from Kezi to Bulawayo at a roadblock. He was 20 at the time and was forced off the bus by the 5th brigade and made to stay at a makeshift detention center.

It was here, he told me, that he saw a pile of human flesh decomposing and later set alight by soldiers. “Most were killed on the false allegation of harboring and supporting army deserters or dissidents”, he said. This was quite a common narrative at the time. Up until the present day, vital documents and information about the democide are not known due to the continued obfuscation of information surrounding the massacres by the government.

State brutality

Police are seen by some as being just another partisan arm of the state. But Human Rights Watch has reported that people “routinely” die in police custody. Human Rights Watch and my own interviews found that the police and Zimbabwe’s Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) often refuse to transfer the bodies of the dead through normal burial processes and sometimes even refuse victims access to their deceased relative. There have also been cases where they denied further investigation.

Meanwhile, the army has been killing people on behalf of the state with impunity since 1980. Witnesses have reported seeing the army digging mass grave in Dangamvura cemetery and piling the human remains inside them. On one occasion, a witness saw the army using prisoners to dig the graves.

The state intelligence services are much more elusive and wield authority over other security departments. They have more resources and can use other apparatus to transfer abductees or human remains. They own properties for training and logistics and some of these locations are are believed to have been used for torture and even burial of human remains, according to surviving witness testimony. This was also confirmed with a witness I spoke to.

Another witness I interviewed went to the Marange diamond fields at the height of government operation in 2008—Operation Hakudzokwi (“do not return” in Shona). He traveled all the way to Marange, about 120 miles from Chitungwiza, with three friends and got introduced to a syndicate leader who turned out to be a police officer. They were then given a map and some equipment and were directed where to go. He told me: “We spent three days in the fields playing cat and mouse with security details. We often heard gunshots in the night. In the day we would see police officers collecting bodies in metal coffins.”

Since 2000, there have been more than 5,000 abductions by the state with about 49 abductions recorded in 2019 alone, according to the UN. I spoke to three witnesses who were abducted, tortured, stripped naked, and then dumped near lake Chivero, which is 23 miles south-west of Harare. One said: “I was bundled into a Toyota Land Cruiser vehicle after being trailed by the unmarked vehicle in Harare. When we arrived near the lake they started beating me up with boots and fists.”

The man said the thugs were demanding to know what the opposition plan was on an upcoming demonstration. When he could not confirm anything, they left him to walk naked to the main road for help.

What happened to the dead?

According to my study of the Gukurahundi killings, bodies were thrown down mine shafts in Antelope, Chibondo, Silobela, Filabusi, and Nkayi. Human remains have been found at schools, hospitals, river banks, dams, and caves. They have been dumped near business centers, disused airports, and at former detention centers like Bhalagwe and Sun Yet Sen, which were set up during elections by war veterans and ZANU-PF youths. In 2011, for instance, a mass grave containing the remains of 60 people collapsed on a field while children played football. Victims who are not claimed at mortuaries are given pauper burials. This makes the search and recovery process even more difficult.

The use of cemeteries, like Hanyani and Kumbudzi, for stacking bodies in mass graves, is a particularly nefarious method. Cultural myths associated with the dead mean people very rarely venture into cemeteries. There is a belief that the spirits of the dead roam those places.

The victims of the Marange fields atrocities were killed by criminal syndicates attached to certain military personnel. They were either buried in the mines or taken away. Those taken away were buried by prisoners in cemeteries in Dangamvura, which is 14 miles away from the mining fields. The army dug two mass graves in Dangamvura cemetery in 2008 and buried over 60 bodies there.

Many of these things are common knowledge in Zimbabwe. Yet despite the alarming number of deaths and kidnaps, the official missing person database for Zimbabwe with Interpol currently stands at just 15. It includes my cousin, Miriam Gonzo, who went missing in South Africa.

Curiously it excludes people missing from the various democides, including journalist and human rights defender Itai Dzamara who was kidnapped by state agents in broad daylight in 2016 while having a haircut.

Clouded in secrecy

Another layer of deception that emerged during the Mugabe era was the issuing of death certificates for the Gukurahundi democide. The vice president at the time, Phelekezela Mphoko, started a program of issuing death certificates to surviving families without any investigation. Such processes will add to the conundrum of trying to identify and reconcile records of the missing in future.

The state often denies all killings and blames them on “insurgents”, “malcontents” and “third parties”. This is the narrative that was offered for the January and August 2019 state killings that saw over 18 people murdered by men in army uniforms. A subsequent inquiry, led by former South African president, Kgalema Motlanthe, concluded that the army was culpable—but there are still no prosecutions as a result.

Despite the death of Mugabe, the government continues to mislead the population. In May three women, including MP Joana Mamombe, said they were kidnapped, tortured, and sexually assaulted by state agents. Not only did the state deny the abductions but they charged the women with breaking COVID-19 lockdown regulations and presenting false information to police.

In 2018 president Emmerson Mnangagwa enacted the National Peace and Reconciliation Act: legislation that facilitated the formation of a commission to look into previous human rights abuses. In addition, the Zimbabwean Parliament is debating the Coroners Act Bill which will establish the office of the coroner to investigate suspicious deaths.

There is a pressing need for human rights groups to compile a comprehensive missing persons database. An independent regulatory authority must oversee this whole process. International organisations, such as the International Commission for Missing Persons, could help.

I hope my research will support this effort and help correct the inaccurate historical record. More importantly, I want to help grieving relatives bury their loved ones and finally achieve some sort of closure.

When I finished my research, the image of my school friend was even more ingrained in my consciousness. It is for people like him, that investigations like mine must be allowed to continue.

Keith Silika, PhD in Forensic Archaeology, Staffordshire University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.