What is owed Africa

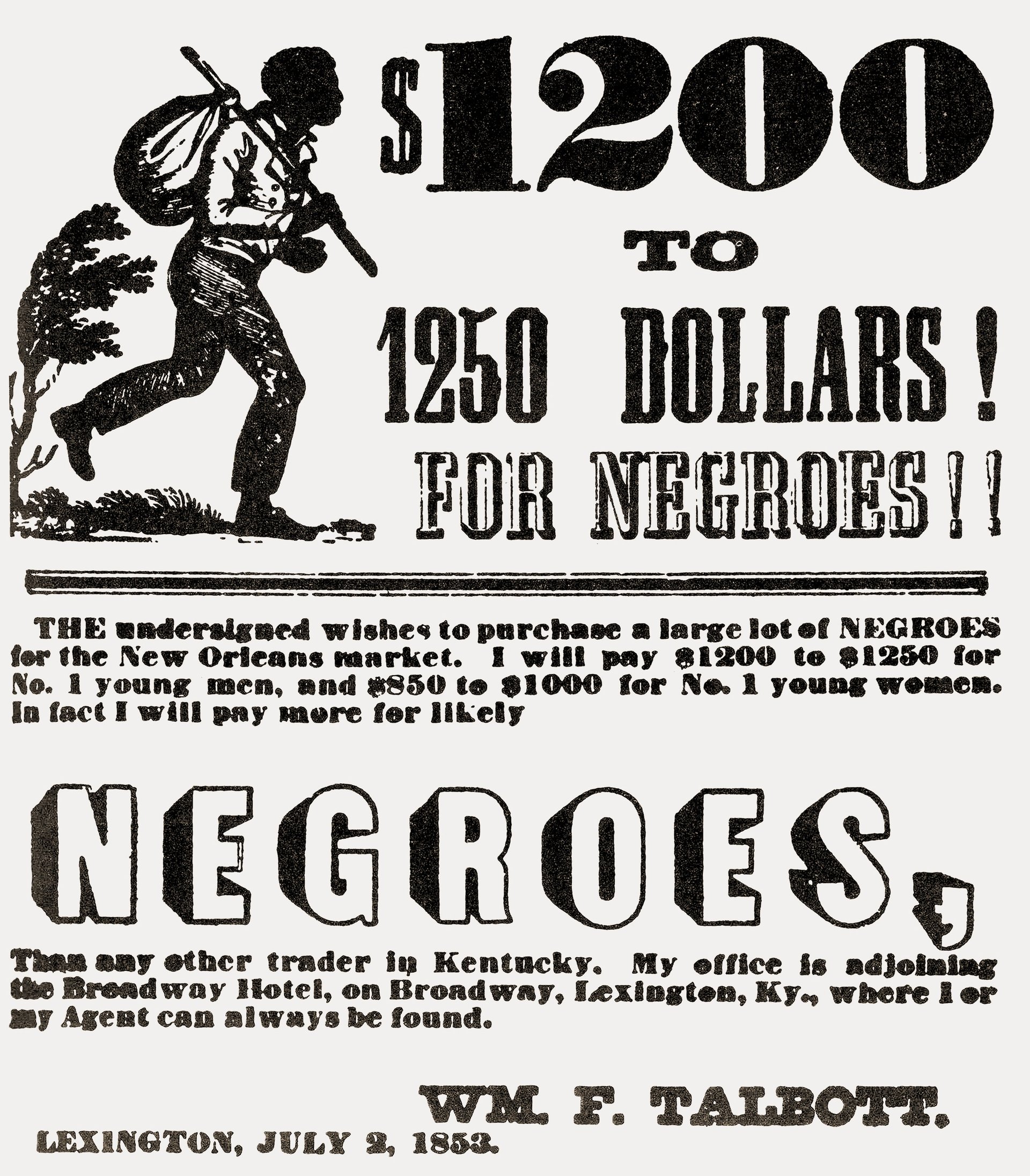

Standing on an auction block in chains, an African man in good health could sell for over $1,200 in New Orleans in the decade before the US Civil War. A girl of nine or 10 could fetch $1,400 under the right market conditions. Pricing took into account a man’s strength or a girl’s ability to bear children for resale.

Standing on an auction block in chains, an African man in good health could sell for over $1,200 in New Orleans in the decade before the US Civil War. A girl of nine or 10 could fetch $1,400 under the right market conditions. Pricing took into account a man’s strength or a girl’s ability to bear children for resale.

Calculating the value of a life is complex, but as slavery has taught us, it’s been done before. For centuries, Africans were reduced to property in North and South America and the Caribbean. Slave traders had no trouble pricing a human life, and abolition-era economists repaid slave owners for the losses of their freed slaves. It’s only when the descendants of those slaves return to ask for compensation for their lost ancestors does counting become difficult.

Similarly, the loss of human life from the African continent due to the trans-Atlantic slave trade had a real cost. Africa wasn’t just deprived of lost manpower and income, but also creativity, innovation, and relationships. Those losses were multiplied by millions of lives, over hundreds of years, stunting the development of a continent whose governments have since struggled to find the will to ask for restitution.

There is no need to further justify reparations for Africans and the African diaspora to redress the legacy of slavery and colonialism. What needs to be discussed now is how those reparations will be paid out and to whom. That will require not only economic dexterity, but empathetic imagination.

Counting the cost

Before the Portuguese arrived in what is today Angola just after the turn of the 15th century, the Arab states had a thriving slave trade on the continent, and Africans themselves enslaved other Africans captured in battle. But it was the trans-Atlantic trade—rooted in capitalism and imperialist expansion, and requiring the mass kidnapping of human beings on an industrial scale—that is perhaps most pressing right now. As Black Lives Matter protests grip the US, and colonial-era statues fall in Europe, the descendants of those slaves—the African diaspora—are demanding justice. It’s time that Africa, the continent on whose losses Europe and the Americas were built, join that demand.

Approximately 12.5 million people were enslaved and taken from Africa, according to a widely accepted figure from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, but some estimates argue that as many as 20 million people were enslaved.

And then there are the population estimates that could have been. Some scholars believe that before the beginning of the slave trade in the middle of the 15th century, Africa’s population could have been as large as 270 million. This kind of population density—15-20 people per square kilometer, the equivalent of Europe—would have led to developments that could have kept Africa in step with the rest of the global economy, according to historians. “Such a dense population must have been predicated on agrotechnological capabilities on a par with those of Europe at the time,” wrote the late Senegalese-French historian Louise-Marie Diop-Maës.

Those estimates reject the myth of an underdeveloped, underpopulated African continent that lagged behind the development of the West. The region had demographic, climatic, and agricultural conditions that made it ripe for progress. To argue otherwise is to rely on a racist notion that Africans simply did not possess the inherent capability to create their own communal and individual fates, a misconception that has often served as a justification for the slave trade and its brutality. For Diop-Maës, any reparations should consider the loss of 100 million lives: not just the 12.5 million captured, but their descendants who might have otherwise contributed to Africa’s uninterrupted development.

Slavery didn’t just deprive Africa of its population, but destablized its institutions. The continent’s economy was reduced to a monoculture of selling human beings at the expense of developing other resources, says Babacar M’Baye, a professor of English at Kent State University in Ohio, whose work quantifies the economic, political, and social impact of the slave trade. “As a result, the once strong and developed African states lost their stability and became fragmented by internal and external conflicts that still affect the continent today,” he says.

African states no doubt played their own role in the slave trade. The entrenched poverty of the Central African Republic, for example, is attributed to the raids and kidnappings carried out by rival tribes in league with European slavers in the centuries before the French carved up what remained. So traumatized were the early tribes, they found it was safer to remain in small groups rather than develop the larger communities that were vulnerable to raiders.

The quasi-aristocratic African slaver class, created through trade with the West, was parasitic and reliant on its connection to the slave ships sailing across the Atlantic, says M’Baye, suffocating any real political power that might have emerged in Africa. The power of these slaver classes was based on their ability to trade with the West, and they were often usurped by stronger mercenaries who took over their trade by force. None of these rulers were viewed with any real legitimacy by the already-fragmented local communities, making it near impossible to establish a political legacy, much less one that could stand up to Western exploitation, or even negotiate a fair exchange.

You get what you ask for

If basing a calculation on what might have been seems beyond reach, reparations activists have refined their calculations, creating a practical model for reparations to Africa for the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the gaping holes in development left behind.

One of the earliest formal requests for reparations to Africa began in 1992, when a group dubbed the “Eminent Persons” came together under the auspices of the Organization of African Unity, now the African Union. It was led by wealthy Nigerian businessman and former president-elect Chief Bashorun M. K. O. Abiola and championed by Kenyan academic Ali Mazrui. The eclectic group also included a US congressman, economists, historians, politicians, and South African singer and activist Miriam Makeba.

For the reparations movement to work, Mazrui argued it needed to connect Africa and the diaspora, creating what he called “a worldwide crusade for reparations for the African and Black world as a whole.” That meant looking beyond money and finding realistic ways to address the imbalance between Africa and the West. Mazrui argued for the empowerment of African people and states in relation to the current world order.

For Mazrui in the 1990s, reparations from Western countries meant reducing their support for African tyrants, supporting democracy on the continent, giving African states a louder voice in international organizations, and canceling their debt.

Mazrui and the group of Eminent Persons devised what they called the Middle Passage Plan, inspired by the post-World War II Marshall Plan. Just as the US transferred more than $13 billion ($140 billion in today’s dollars) toward the rebuilding of Europe, so too would former slave-owning and colonial nations transfer capital toward rebuilding Africa. The Middle Passage Plan (paywall) would include a skills transfer to Africa with scholarships for African students. The plan also called for a power transfer, giving greater voting rights to Africans on the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the United Nations Security Council.

To those overwhelmed by how to calculate the value of these reparations, Mazrui devised a “ledger of reparations” and a “calculus of causality.” The calculation relied on rough percentage estimates of how much of the present underdevelopment and inequality was linked to the past. For Mazrui, it was roughly 40%, but just how to calculate that percentage generated more unknowns than knowns.

“We are dealing not merely with the history of bondage, but also with the bondage of history,” Mazrui said in a 1992 lecture in Boston. “The history of bondage includes, of course, the history of enslavement and the slave trade. The bondage of history, on the other hand, is the extent to which, to a considerable degree, we are all prisoners of our history.”

That extent would need to be calculated by another generation. The Eminent Persons avoided assigning a number to each life lost, arguing that it would trivialize the victims’ sacrifices. However, a Truth Commission in Accra tried to do just that in 1999, reaching a total of $777 trillion, excluding interest, although how they arrived at that figure is unclear. Another figure, calculated by academic Daniel Tetteh Osabu-Kle in a 2000 article published in the Journal of Black Studies, put the cost of reparations at $100 trillion, assigning a value of $75,000 per person lost, based on a model of the historic development and population growth of Asia over the same period.

A missed opportunity

About a decade later, a new group of Africans took up the discussion at the United Nations World Conference against Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance in Durban in 2001. At least three of the Eminent Persons group were in attendance and the request remained largely the same. Africans entered the discussions with confidence and gusto, finally able to collectively put their demands for redress to the representative of a system under whose boot they still suffered.

“The discrimination we see today is a social atavism of the centuries of inhuman practices,” said Enoch Kavindele, former vice president of Zambia, at the conference. “We have a chance and an opportunity today to contribute to a better world where racism and discrimination will come to an end.”

Despite a robust debate from non-governmental organizations, African government representatives seemed to have lost their nerve. While the final declaration acknowledged slavery as a crime against humanity and that colonialism led to racism and racial discrimination, it left loopholes. It acknowledged the victims of these wrongs have the “right to seek just and adequate reparation and satisfaction,” but fell short of creating an internationally recognized and binding agreement.

The final wording also reflected lobbying by the Netherlands, the UK, Spain, and Portugal—all former slave-trading nations—that an official apology would leave contemporary governments open to lawsuits. Many were dissatisfied with the agreement but conceded that it would at least lay the foundation for future talks. The conference ended on Sept. 7. Just days later, the Twin Towers would fall in the 9/11 attacks, shifting the world’s attention and reshaping the geopolitical arena.

Nearly 20 years later, Kavindele says African leaders have lost the sense of pan-Africanism that drove his generation to demand an audience with former colonial leaders.

“The new leaders who have come have not been the original freedom fighters—these are subsequent leaders who have found most things already made, already there,” said Kavindele, now a wealthy businessman. “The new leaders are happy to go to the IMF and the World Bank to talk about loans to their countries, and yet I think they should be talking about compensation and reparation.”

“There’s always the fear that they do not wish to ruffle the feathers of these powerful institutions,” he added. “ Those are the same people, the same institutions that owe us money.”

Kavindele is hopeful that the African Union today could negotiate as a bloc, and work out an equitable redistribution of reparations. The obstacle to that, he believes, is the same one he encountered in Durban all those years ago.

“The sharing is not too much of a problem. The problem is the ability of the former colonialists to pay.”

Who will ask and who will answer the call for reparations

The conversation about Western nations paying reparations has since stalled, with few new ideas. In the intervening years, there hasn’t been much reason for optimism.

“I haven’t seen anything suggesting it’s going to get very far,” said Rhoda Howard-Hassmann, author of Reparations to Africa. Howard-Hassmann interviewed some of the Eminent Persons and researched the outcomes of the Durban conference. She came away with the conclusion that while reparations are just and certainly needed, framing the request would be a much harder task than proving their justification.

Apart from a somewhat left-field case for reparations owed by China and wealthy nations for mishandling the coronavirus pandemic made by Nigerian cabinet minister and former World Bank vice president Obiageli Ezekwesili, the call for reparations from the continent has waned. Instead, it has taken on a more cultural tone, turning to a dialog about returning stolen artifacts to Africa. This is important for restoring some of the continent’s cultural identity, but even the return of art, ceremonial objects, and human remains is tangled in legal red tape and governed by the power imbalance between the West and Africa. This time, though, it’s playing out between haughty European museums and disenfranchised African communities.

Reigniting the debate on meaningful reparations would need a condensation point, said Howard-Hassmann, a moment or movement that would create real impetus around reparations, and someone willing to make the case for it. In the US, that catalyst could be the current movement against racism motivated by recent instances of police brutality. Indeed, California recently agreed to assess the call for reparations. But Howard-Hassmann has been discouraged by pushback from Trumpian America, and by the rise of right-wing governments around the world.

When former US president Ronald Reagan signed a bill granting reparations to Japanese-Americans for internment during World War II, the US Congress was much less divided, providing the requisite political will. Even though scholars and politicians have today been able to draw the line of causality between past and present injustice, using practical examples like red-lining in the Jim Crow era, paying reparations first requires a perpetrator to face and admit their shame.

This is partly why the Kenyan Mau Mau torture victims’ case in 2013 against the British was successful: The current British government had to face the victims as they told their harrowing stories from more than 60 years ago. Likewise, in the case of the Jewish victims of the German Holocaust, the victims and perpetrators were clear, as were the losses incurred. Had Jewish people asked for reparations for the centuries of marginalization and expulsion in Europe before World War II, it would have been much harder to make a successful case, says Howard-Hassmann.

“What it boils down to is the more recent the atrocity was, the shorter the period of time and the clearer it is who the victims were and the perpetrators were, then the more persuasive a social movement is,” she says.

The case of Namibia

In Africa, Namibia has tried to pursue a similar case against Germany for the early 20th century genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples. Yet even here, where there are records and admissions of shame, calculating reparations has proven difficult. The two countries have not only wrangled over the amount and form of reparations, but the very word itself.

Germany’s offer of development aid to Namibia echoes similar arguments from other colonial powers: that aid to the continent should suffice. But decades of foreign aid have created economies in Africa that are reliant on Europe and North America, following the geographical route of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and mimicking that unequal trade. Aid also fails to acknowledge the psychological and emotional impact of the slave trade.

Germany has also avoided using the term reparations or putting forward an official apology, while Namibia says money without an admission of guilt would be an insult. The stalled talks and the decades it has taken Germany to even acknowledge wrongdoing speak to the lopsided relationship between Africa and its former colonial oppressors, and to Mazrui’s point that any reparations must first address Africa’s position on the world stage. These relationships are still influenced by colonial-era power structures, even if, as at the 2001 Durban conference, shame and injustice are acknowledged.

If the discussion on reparations to Africa were to restart in earnest, it must begin with the West’s acknowledgement of its wrongdoing, if only to address what is perhaps the most difficult effect of slavery and colonialism—the psychological impact and the enduring legacy of racism in the world.