I was the envy of friends and peers when I left for America. The promised land. Living under a brutal tyrant in a country where freedoms are few, many young Zimbabweans are desperate to leave and discover from the world everything denied them.

Perhaps, because I work as a journalist and confront injustice and discrimination all the time, I am wary of illusions that places such as America are made of. This country is not what it seemed from outside. There is something about America that has kept the black man a perpetual victim. Its structures and institutions are still designed in a way that favours one race over the other. The police force is to black people the most visible fact of American racial ambivalence.

These stories of discrimination, hate and murder are damaging to the morale of a country that describes itself as “land of the free.” If America was truly multiracial in its habits and outlook, in its history and politics, the race question need not detain us anymore.

They do, just as all lives matter. It is a pity that innocent black lives continue to be extinguished and summarized as periodic hashtags.

When Dylann Roof, 21, killed nine black people fellowshipping in the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina he said that they (black people) were “taking over our country. And they have to go.” This mass-shooting, in a sanctuary of worship, follows months of racially charged protests over the killings of black men and women which have been shaking American society to its core.

President Barack Obama hints as much in his speech to honour the victims, “at some point, we as a country will have to reckon with the fact that this type of mass violence does not happen in other advanced countries. It doesn’t happen in other places with this kind of frequency. It is in our power to do something about it.”

Some see the liberal gun policy in America as the problem. Dylann Roof’s father gave him a gun, as a 21st birthday present, his key to the world, two months ago. Whether he used the same gun or another is inconsequential. He went to kill people who had not wronged him. And they were black. Too often, in America’s contemporary imagination, terrorism is foreign and brown.

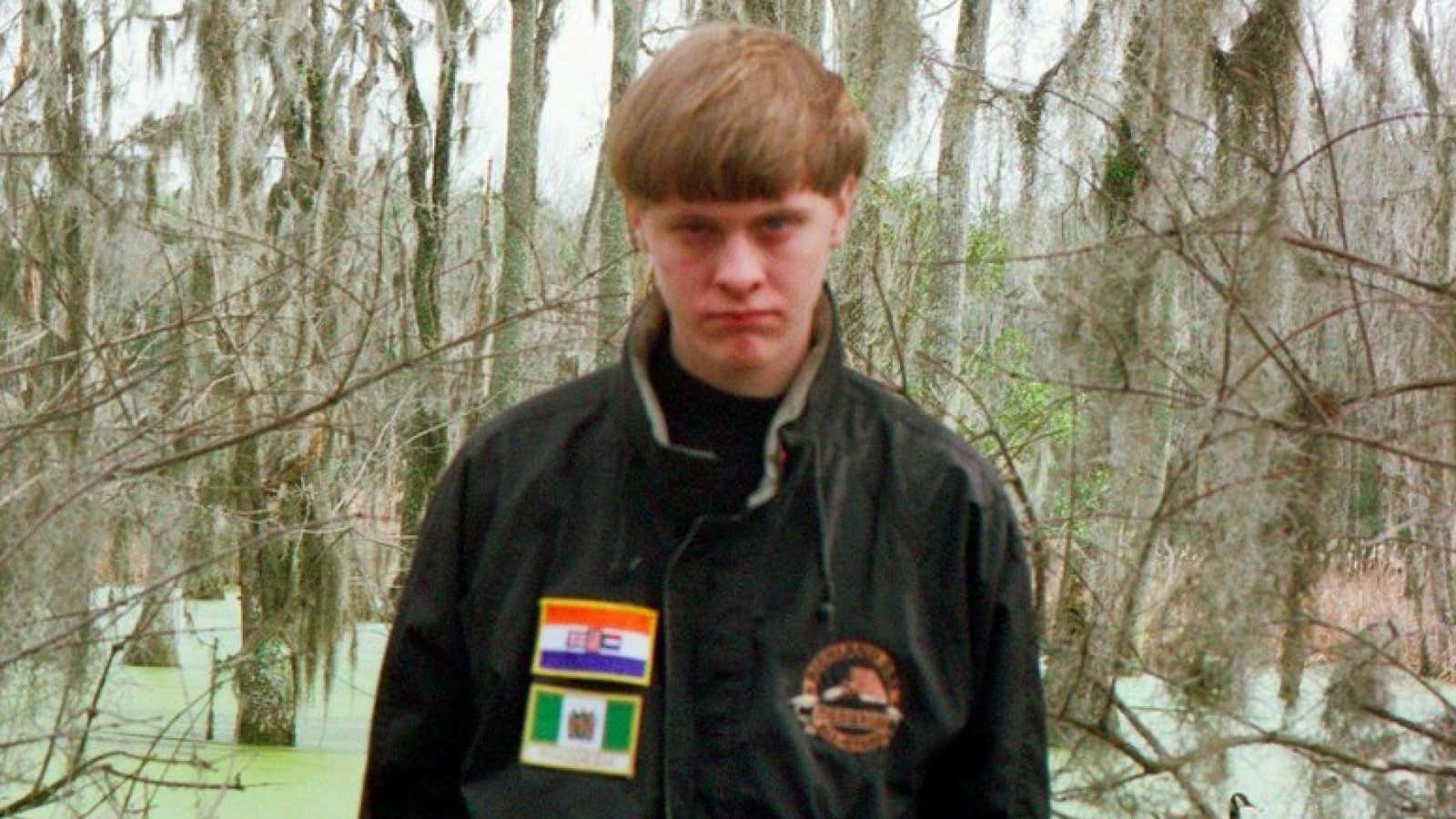

In one of his pictures that is viral on social media he is glaring at the camera and wearing a jacket with racist colonial insignia, two flag patches that represented apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia. Apparently, laying claim to these defunct colonial states is a way to build street cred in white racist circles. When I saw the image it flickered scenes from my own history.

Rhodesia is a country of horrors from my past. To see a young American wearing its symbol as a statement was repulsive. Millions of black people were disenfranchised, killed, maimed to preserve the idea of white supremacy in the troubled country we now call Zimbabwe. After declaring the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965, a defiant Ian Smith, said, “No African will rule in my lifetime (not in a thousand years). The white man is a master of Rhodesia. He has built it, he intends to keep it.”

Unfortunately for Smith and those like him white supremacy did not last. However, the damage it had created would last beyond it. Black majority rule came in 1980 after a bloody war even though it has not been as many wished. Yet that war radicalized a generation of young Zimbabweans, among them my parents, to believe that they could dream and fight for their rights. To hear them talk about growing up in Rhodesia is like hearing them talk about life in another world that should have never existed. They were discriminated by skin colour, language, access, for the comfort of a small white minority. And shockingly, the flag of South Africa’s apartheid government is still on a plaque in Albany:

No wonder it is difficult for some section of white America to accept blacks as equals, for to do so is to jeopardize their perceived privilege. America is still glaringly black and white, a human separation, which is taking forever to bridge.