Allan Pamba qualified as a physician at the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in East Africa. Health systems across the region were overwhelmed by the disease, and international resources were slow to be mobilised.

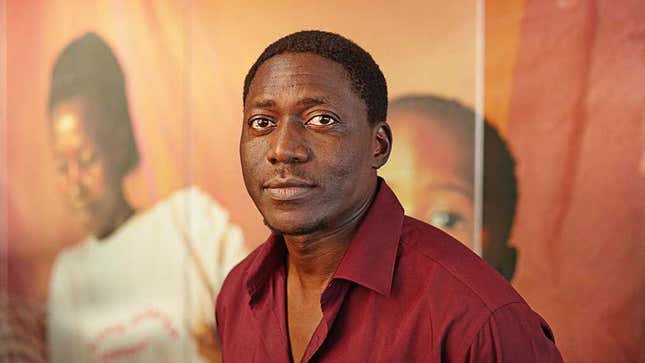

“As a junior physician, I probably signed off way too many death certificates than I should have,” Pamba, now vice president for East Africa at GlaxoSmithkline, says. “Through that process we almost watched a disease go through its natural progress on a curve, which is probably a physician’s worst nightmare.”

The HIV epidemic was socially and economically devastating for much of Africa, but a decade of regional and international efforts have reduced its impact. Likewise, deaths from malaria–which killed more than a million Africans a year in the 1990s–have reduced, due to a huge focus on prevention and treatment.

But now Pamba warns of “another tsunami”, for which African healthcare systems are unprepared: diseases that are arguably the consequence of the continent’s rapid economic growth and the changes that go with it.

High GDP growth rates, urbanisation and the consequent creation of a new middle class in sub-Saharan Africa has fostered an ‘Africa Rising’ narrative that has drawn in investors.By 2030, half of all Africans will live in cities; the African Development Bank estimates that the continent already has a consuming class of around 300 million people. Global fast-food brands are pushing deeper into markets that once would never have registered in their plans. Burger King is due to open in Angola and Zimbabwe, KFC in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ethiopia. The continent is increasingly a profit center for global brewers like Heineken, SABMiller and Diageo, and a rare bright spot for cigarette sales in a world that is giving up on tobacco.

New, high-consumption, sedentary lifestyles, combined with greater life expectancy, have led to a building wave of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) – cancers, respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular disease and other maladies associated with urban living. Currently this category is responsible for around 35% of mortality on the continent; by 2020, the World Health Organisation forecasts it will rise to 65%.

“I’m hearing a lot more about cancer, stroke, long-term diabetes. Those were pages in my medical school textbook that we were told: if you skip those pages, it’ll be fine. You’ll never see that in your lifetime,” Pamba says. “We were told to read about malaria, read about tuberculosis, read about the communicable diseases. My training in this area [of NCDs] was deficient, as it was for many other physicians that are practicing now, because we didn’t foresee this happening in our lifetime. But they are becoming a problem. We do not have the capability to deal with it. We do not have the manpower trained in sufficient numbers. We don’t have the medicines to treat when we fail to prevent, and we don’t have the healthcare infrastructure.”

Tool Deficit

Even regional hubs, such as Nigeria’s commercial capital, Lagos, and Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, lack the sophisticated oncology and cardio-vascular facilities required to treat their current patients. Many, if they can afford it, go to India, Singapore or the Middle East for treatment.

The legacy of decades of international investment into tackling communicable diseases is that most of Africa’s medical infrastructure is arranged in silos – created to treat individual crises.

“Our current model is only geared towards ‘when something goes wrong, we’ll address it’. That requires lots of expensive interventions. It’s an in-crisis model,” says Ernest Darkoh, founding partner of Broadreach Healthcare, which advises governments on building inclusive healthcare systems.

“I arrived in South Africa in 2006. A lot of our work is in rural areas. You would go into KwaZulu Natal, ask people ‘Do you have diabetes?’ and they’d say ‘Not yet.’ It was that normal, that you get diabetes at a certain point… I remember thinking, ‘Oh my god. This is a powder keg waiting to explode.’”

NCDs require an entirely new approach to building healthcare systems, Darkoh says. Public health has to move away from “crisis mode” and into a broader understanding of a patient’s lifestyle, wellbeing and ongoing needs. The current system, which he describes as “curative,” is “innately flawed,” he says.

Addressing the issue means more than just building scale, according to Darkoh.“In Africa, thinking that we might have as many cardiologists as America one day is a pipe dream,” he says. And, by the way, America doesn’t have enough cardiologists, despite spending trillions of dollars a year on its health systems.”

Upgrading healthcare infrastructure

Echoing Pamba’s sentiments, Darkoh believes that healthcare infrastructure will need to focus as heavily on prevention and lifestyle as it does on curing those who are already sick, learning the lessons from the HIV/AIDS epidemic, where too much emphasis was put on the latter.

This means, for example, educating people on their lifestyle choices and screening for cancer early. A vaccine already exists for the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can lead to cervical cancer – according to the WHO, the leading contributor to years of life lost from cancer among women in the developing world. Rolling that out – as Rwanda is now doing – means linking health into education systems to ensure that school-age girls are covered.

Heading off the NCD wave needs what Darkoh calls: “A conscious, joint planning paradigm, where we all own a piece of [the patient] and his wellbeing.”

This, though, requires a high-touch process that seems light years from the current structure, where contact with healthcare professionals is very limited and where interventions, records and infrastructure remain in silos.

“We need to develop the kinds of healthcare systems that can capture patients with chronic diseases early, connect them into the system, and then most importantly we need to understand how to retain them in the system,” says Anuschka Coovadia, head of healthcare markets in Africa for KPMG.

Such systems would lean heavily on technology. A common IT platform for patients’ records would allow doctors to make sure patients are getting the right care and refer them to specialists when necessary, Coovadia explains. But that’s difficult in a continent where few countries have adequate medical records.

Some companies are already looking to fill this data gap. IBM built a system to help the government of Sierra Leone map and respond to the Ebola outbreak last summer. It took in various “non-traditional” sources of medical data such as text messages and phone calls.

The same idea could be applied to NCDs, according to Alan Kalton, the program director for IBM Research in Africa. “The traditional view of what a healthcare record is lends itself to a certain set of analytics, but here we have a lot of adjacent data sets that could be very relevant [to NCDs],” he says. Last year, for instance, his team built a model for predicting the best ways to fight cervical cancer. One of the most important pieces of data they used, he says, was not health data but school attendance records, since one of the key methods in fighting that kind of cancer is screening school-age children.

How technology helps

Mobile healthcare – or “m-health” – has been held out as a potential solution for a whole range of public health problems since the African telecoms boom began a decade ago. Today, mobile-phone penetration in Africa is around 65%, and smartphone usage is rising as phones become cheaper and data services are rolled out.

This has already revolutionized financial services.– In more than a dozen African countries, mobile wallets outnumber traditional bank accounts. Medical professionals are hoping that cellphones will allow them to remotely treat patients and build the datasets that will help them deal with future health problems. As yet, though, there have been no break-out applications.

“We still have the problem that it’s difficult to weed out which of these technologies can scale, and to support them to bring them to scale,” says Pamba, of GSK.

But although he is hopeful that technology can help, Pamba’s prognosis is bleak. Public resources are already stretched. At the turn of the millennium, African leaders pledged to spend 15% of their GDP on healthcare. Fifteen years later, the average is only 6.2%.

“I don’t think people are sufficiently scared about it,” he says. “When you lived through the HIV epidemic and looked people in the eye and saw how tragic it is to lose 18-year-olds, 21-year-olds, you look at the NCDs now, and you think people need to get scared now, not when the tsunami hits us.”