At the recent Quartz Africa Innovators Summit in Nairobi, the Kenyan journalist and activist Boniface Mwangi suggested that Africa needs a revolution. Not a violent one, he said, but a revolution at the ballot box. ”We need to be active citizens,” he explained onstage. ”We must dare to invent the future and reclaim our continent.”

Important elections have been happening in Africa this year, with mixed evidence for democratic progress. In Nigeria, the continent’s largest economy, the electorate voted in the opposition for the first time in the country’s history. Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, one of Africa’s fastest growing economies, elections held in May returned the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front to power with an extraordinary near-100% of the vote. Tanzania is currently embroiled in the most competitive presidential campaign in memory.

More than half (52%) of Africans polled believe that their countries are democratic, according to data from the research firm Afrobarometer, released on Sept. 15, from a survey conducted in 28 African nations. But when it comes to individual countries, a diversity of perceptions emerges on the state of democracy on the continent, allowing a more nuanced view of the state of democracy in Africa.

Over 70% of Namibians and Batswana polled said their countries are democratic. Meanwhile, only a third of Nigerians think so about their nation (it is worth noting that the survey had been conducted prior to the recent elections that put Muhammadu Buhari into the presidency.)

Overall, only 46% of Africans are satisfied with their national democracy, a slight drop from 50% in the last poll done in 2013/2014. Mali, a country that only two years ago was enveloped in a civil war, has seen the highest rise of democracy satisfaction of the 28 countries surveyed.

Ghana, once a beacon of democratic transition in the continent, has seen a significant jump in the electorate’s dissatisfaction with democracy.

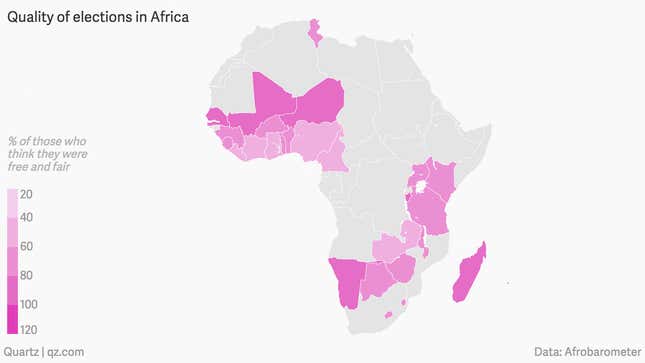

Despite this atmosphere of disillusionment, 70% of Africans in the 28 states surveyed believe that elections were free and fair in their countries. (The survey was conducted before political troubles in Burundi began and the election in Nigeria.)

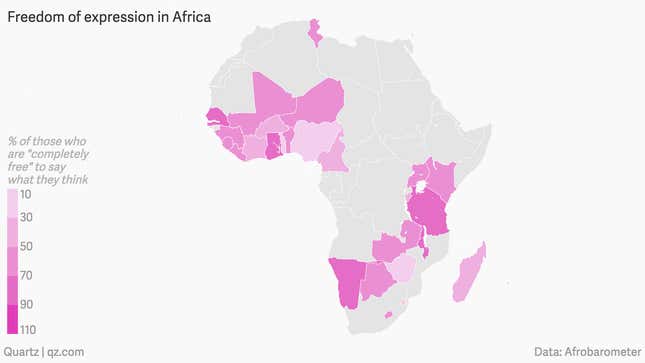

Free and fair elections are one thing when it comes to the question of democracy. Another important indicator is freedom of expression. And here, the response is more sober from those polled. Fifty-one percent said they feel free to speak their minds, with 26% “somewhat free” and 22% saying they are “not at all” free to express their views, the Afrobarometer data shows.

Another useful indicator on the state of democracy in Africa is freedom of political association. Only 15% of people from the 28 countries surveyed said they did not have a choice on who they could associate with politically. This, combined with the question of free speech, is an important window into democratic daily life.

Zimbabwe, for example, scores high on voting, with 68% of citizens reporting that the last elections were free and fair. But this tells only part of the story. The fact that Zimbabweans give their country low marks on free speech and political association suggests that things are not as positive.

On the whole, though, African voters believe they are free to make their democratic choices at the ballot box. Seventy-three percent of those polled feel they can vote for whoever they want. That is progress.