This is a particularly thrilling year to be a Ugandan.

For 77% of the country’s population, born since 1986, 2016 could be the year they witness, for the first time, a new president get elected.

Well, in theory anyway.

Uganda’s president Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, 71, has been in power since Jan. 29 1986—just over 30 years. What originally started out to be a one-term presidency for the heroic guerrilla fighter soon turned into the same “overstay in power” that Museveni himself once denounced as the reason for Africa’s slow progress.

The generation of people born since 1986 is often referred to as ‘Museveni Babies’. They have only known one ‘father’. The presidential and parliamentary elections are taking place on Thursday (Feb. 18).

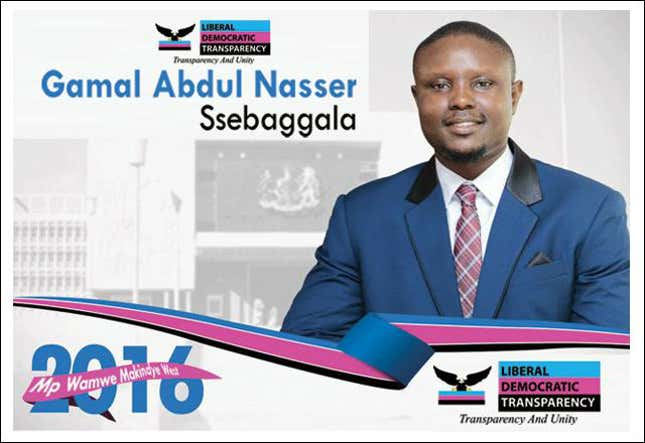

Gamal Abdul Nasser Ssebaggala, 29, and Amanya Tumukunde, 25, are two such young men running for election to Uganda’s parliament this season.

Due to a heavy concentration of retail small businesses in Makindye West, Ssebaggala, a son of a former mayor of Kampala, believes the constituency he’s running for in Kampala is strategically poised to become the next retail capital of the region. After seven years studying in Beijing, Ssebaggala returned home in order to put his international trade knowledge to work. He started a factory that makes iron sheets. What he encountered on his return were frustrated people who had played by the proverbial rulebook on succeeding in Uganda. “I spoke to parents who thought the plan was simple; “educate my kids so that they can have a better life. I educated my kids and now they are at home seated with me,” he recalls.

Tumukunde, whose father is a retired general and former ally of Museveni, echoes similar points in his campaign. “There’s an inability [for youth] to express oneself despite having the necessary qualifications.” His manifesto pushes for an overhaul of the education system in order to strengthen competitiveness on the global stage. For him, that is a more urgent issue compared to the “dramatic changes” stressed by the candidates opposing the president. Tumukunde is running to be the Youth MP of the country’s Western Region.

Both men are running as independents against Museveni’s ruling party, National Resistance Movement (NRM).

“Ndeese Magezi G’e China”

Despite the bleak sentiments, Ssebaggala thinks there is promise for the future. With many small businesses anchored in Makindye’s thriving retail industry, he believes the best machinery and training can turn the area into a manufacturing hub. His campaign slogan—Ndeese Magezi G’e China—a Luganda phrase roughly translated, ‘I’m bringing the smarts of China’, embodies his manifesto. He proposes an ambitious business partnership between Uganda and China that positions the economic giant as a mentor that can help Uganda industrialize quickly.

China’s interest in Uganda runs deep. Between 1993 and 2012, pledged investments from Chinese firms reached a whopping $683 million. In 2013, the Chinese government awarded 40 Ugandan students scholarships to study in China. Every year since then, the number of Ugandans studying in China has steadily risen. In exchange for oil wells and food crops, the Chinese government has built roads, hospitals and paved the way for private investors from the motherland to sow seeds of opportunity in Uganda.

Ssebaggala and Tumukunde firmly believe Uganda’s youth are aggressively searching for means to determine their economic agency more than a shift in political leadership.

“The biggest victim of NRM’s mediocrity has been the youth,” says Godiva Akullo, 25, a Cavendish University law lecturer and sociopolitical commentator.

Akullo believes there’s a wide gulf between the government and young people. “A lot of politicians are so out of touch. How do you expect to deliberate the budget for a hospital where your family has never stepped in?”

As Ugandans head to the polling booths this month, many Museveni Babies will have to decide whether they can give up the status quo to explore new opportunities with a fresh leadership, or keep the fragile sense of peace and stability that promises an elusive steady progress.

Tumukunde is surer of the future than most. “I really do think we’ll have the same president in the next five years,” he says. According to him, the youth’s spirited interest in the way the country is run is indicative of the country’s high literacy rate—a feat that was managed under the current regime.

Whether Museveni wins this upcoming election or not, Uganda’s youth will be looking to their leader for mostly one thing; a sincere investment in their future.