Cape Town, South Africa

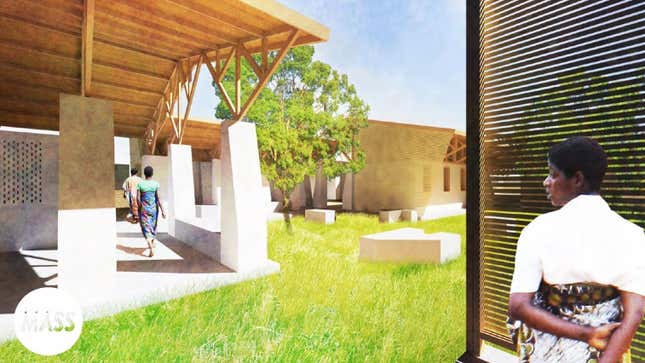

There’s a courtyard with a space for gardening, cooking in a shared kitchen, and laundry done under the shade of a roof that collects rainwater. The Maternity Waiting Village at the Kasungu district hospital in central Malawi emulates the communal spaces of traditional villages. The goal of the design is to attract expectant mothers from remote areas to the facility before giving birth.

Too often, pregnant women in Malawi, and other African countries, give birth at home because hospitals are far and commuting there is too expensive. While maternal mortality rates around the world have dropped drastically over the past two decades, they’re still far too high in Africa. Malawi is home to one of the Africa’s highest maternal mortality rates—510 deaths (pdf, p. 33) per 100,000 live births as of 2013, compared to the average of 239 deaths per 100,000 births in developing countries. The African continent accounts for the vast majority of global maternal deaths—550 of 830 deaths a day last year, according to the World Health Organization.

The design and development of the village, which was completed last October, was done by MASS Design Group, with Gates Foundation, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Malawi’s health ministry.

“Our approach is, let’s leave the big open ward of 45 people and reduce [it] to smaller rooms and have intimate outdoor spaces,” Christian Benimana, a Rwandan architect with MASS Design who led the project, told Quartz at the Design Indaba conference on Feb. 19th. “They can live close to how they are living in their own homes in their villages where they spend most of the time in the courtyards with their friends,” he said.

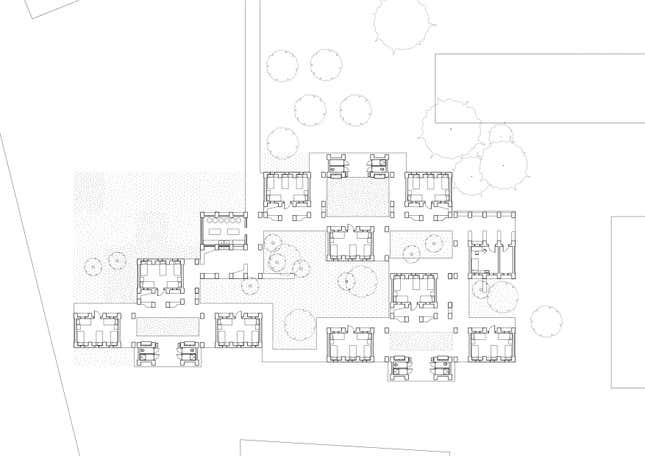

Expectant mothers who are at high risk of health complications are advised to stay at the maternity village between two and four weeks before moving to the hospital to give birth. Women who live in rural areas, far from a hospital, are asked to come early so that doctors can identify and monitor any complications early. Benimana hopes the shared spaces of 12 women per cluster will encourage new, and more experienced mothers, to interact, creating a “sense of security and belonging.” Up to 45 women can be housed in the village.

Public health advocates have promoted ”maternity waiting homes” since the 1960s as a way to bridge the gap between urban and rural healthcare access. Previous attempts to build a maternity waiting home in Malawi have failed because of risks of infection and poor ventilation, according to MASS Studio. The Kasungu village works around this by focusing most of the activities outdoors and designing the houses to let in air and light.

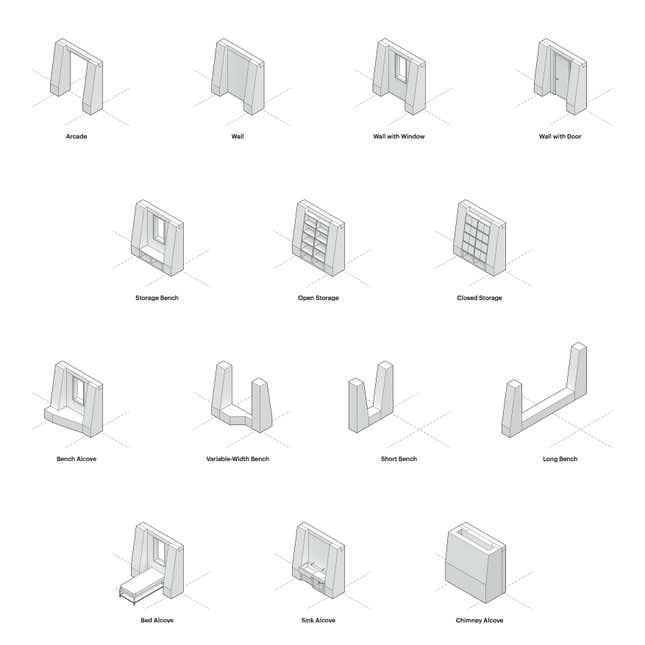

Building smaller units is cheaper and modules for the buildings, made locally, are designed to be easily replicated. This model allows for hospitals and local governments to build and expand as their resources allow.

Benimana says, “Architects don’t just design and build buildings. We think about systems. How do we take the inherited natural architecture and change it into the built environment? That’s the mission of architects.”