Africa’s largest stock exchange, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in South Africa, is about to get some competition on its own turf.

ZAR X, self-described as “a low-cost, simple and convenient trading platform that empowers ordinary South Africans with shareholdership opportunities,” was granted a conditional license by regulators to start trading by September. The new exchange plans to simplify trading through same-day transactions and will not charge custody fees, according to founder Etienne Nel.

Another exchange, backed by one of South Africa’s richest black families, the Maponya Group, is awaiting its certification from the regulator. 4AX says it will focus on low-trading and moderate compliance processes to give more black-owned businesses access to the stock exchange. A third contender, A2X, says it is targeting the top 50 to 65 largest companies already listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

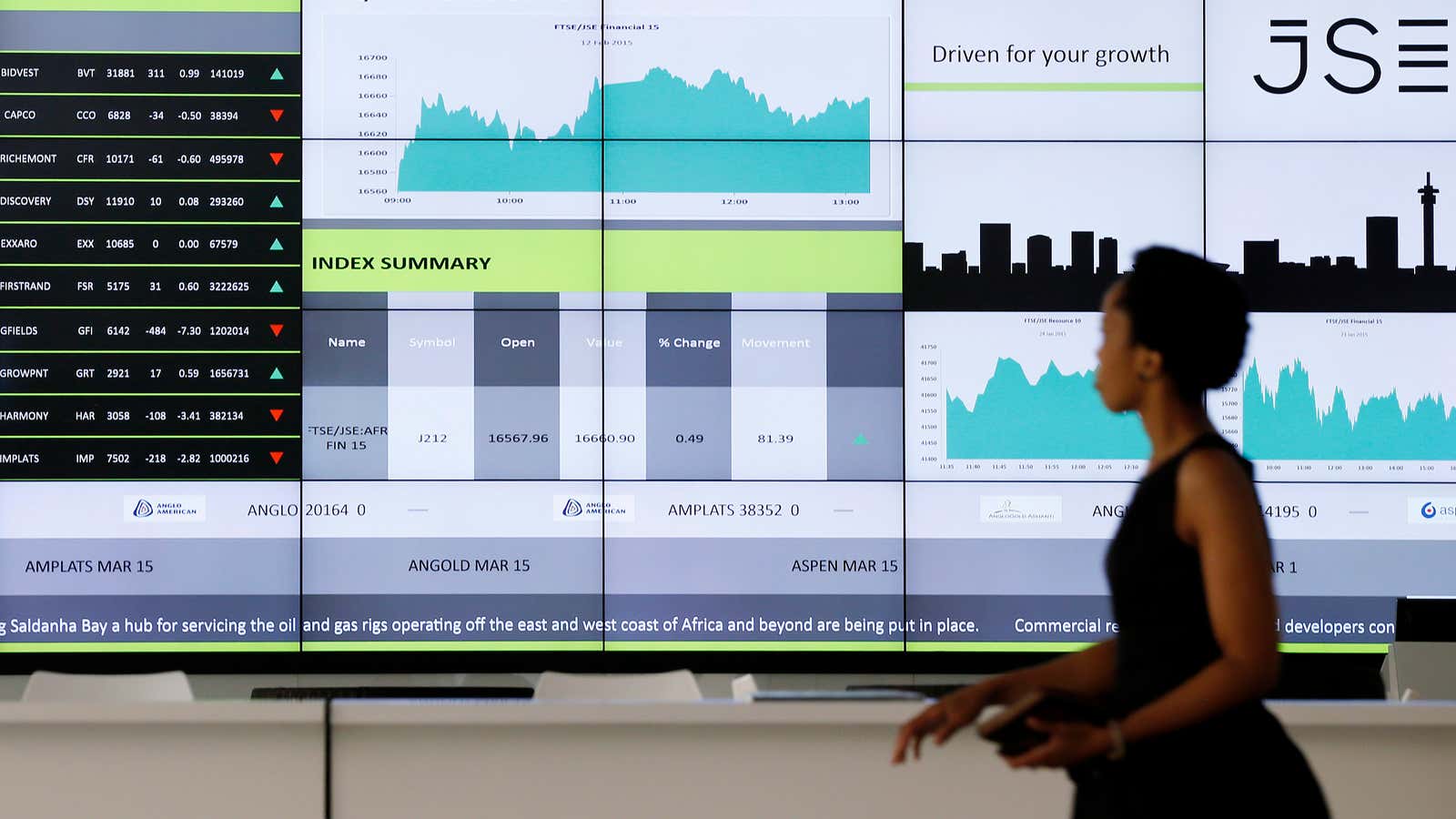

But the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, with a market capitalization of $150 billion, has little to worry about, according to economist Jannie Rossouw. Founded in 1887, competing exchanges born from gold and diamond rushes and colonial wars, did not stop the exchange’s growth, he said. The JSE All-Share Index is down just 1.3% over the last 12 months, but it’s up 4.6% so far in 2016.

If anything, a little competition will be good for investors, as rival stock exchanges in other middle income countries like Chile and Brazil have shown, Rossouw wrote in The Conversation.

“More than one stock exchange in a country offers investors choice and rivalry puts a limit on the ability of a monopoly stock exchange to charge inflated prices for trading and settlement services,” the economist said.

The line of stock exchange applicants may have something to do with stricter trading regulations in South Africa. In 2014, market regulators introduced stricter rules that stopped some smaller unlicensed companies trading their stocks privately. This has created opportunities for new nimble stock exchanges.

Many of the private traders were part of Black Economic Empowerment and agricultural schemes and some critics argued that the stricter regulations could exclude new traders who were only just beginning to learn about the market in a country where the black majority have been historically excluded from stock trading.

At the end of 2013, black South Africans held about 23% of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange’s Top 100 companies, with white South Africans holding 22%, and foreign investors 39%, according to the exchange’s own report. But direct investment only accounted for 24% of total investment in the Top 100 firms, 7% is held by individuals. Of that, black people make up less than 1%.

The Johannesburg Stock Exchange’s has also been criticized for gleaning this data from its Top 100 listings, saying it gives a fuzzy picture of an unchanging financial environment.

Some analysts, like financial journalist Phakamisa Ndzamela, saw the stricter regulations it as an opportunity for black shareholders to gain a footing in the exchange environment. And it looks like they have.