In the Democratic Republic of Congo everyone knows Moise Katumbi—and a lot of people like him. This is rare in a country as vast—the same size as Western Europe— and as fragmented, the national electrification rate is less than 10% of the population. This week, Katumbi confirmed what many have long suspected: he wants the top job, the presidency. Many obstacles, however, stand in his way.

If Katumbi, 51, fulfills this grand ambition, it will have been in no small part due to a recognition and appeal his opponents cannot hope to match. TP Mazembe, the football team he owns, is responsible for much of his popularity. The Congolese champions are currently the continent’s pre-eminent soccer team after triumphing in the 2015 African Champions League and a source of considerable national pride. Mazembe recently represented Africa in the FIFA Club World Cup in Japan.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, Katumbi is also a multimillionaire, one of the wealthiest people in one of the world’s poorest countries. His precise wealth and the extent of his business network remain opaque but Katumbi’s companies have long been very active in logistics and subcontracting in mineral-rich Katanga. Beneath the soil of this southeastern province (which was recently split into four) lies much of the DRC’s world-beating natural resources, mainly copper and cobalt. It happens to be both the DRC’s economic engine room and the region of which Katumbi was governor from 2007 to 2015.

Influential ally

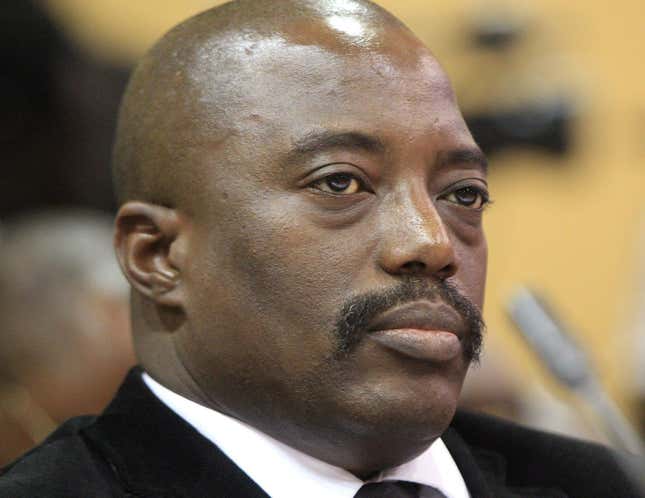

Until last year Katumbi was an influential ally of the man he now seeks to replace, Joseph Kabila, the DRC’s president since 2001 and first elected in 2006. Despite being entrusted to run the country’s most important province, relations between the two men have long been thought to be frosty. The relationship has worsened further since Katumbi’s resignation from the president’s political party last September and his emergence as a leading opposition figure.

After breaking with the government Katumbi immediately set about trying to win the support of as broad a platform as possible. Having secured the nomination of three opposition coalitions, this week he finally declared his candidacy. In an emailed statement, Katumbi said that he accepted ‘with humility this heavy responsibility’ and promised to start a national tour across the country within days’.

His route to the presidency is anything but certain. For one thing, the presidential election will be a one-round affair and the opposition stands a much better chance of success if they put forward a single candidate. Katumbi will have to be very persuasive to convince the leaders of the unpledged opposition parties to back him. Much will depend on the decision of Etienne Tshisekedi, the famously obstinate octogenarian who heads the largest opposition party and considers himself the true winner of 2011’s deeply flawed polls. How Vital Kamerhre, who finished third five years ago, proceeds will also be significant.

Katumbi also now finds the full force of Congolese state power deployed against him. In the weeks before he announced his intention to stand for the presidency, a rally at which he was due to appear was violently dispersed and several of his family and closest associates arrested. They are still being held.

On the morning of his declaration, Kabila’s justice minister launched an inquiry into allegations Katumbi was using mercenaries to recruit Congolese youths into a militia. Katumbi has rejected such claims as defamatory and ‘grotesque’.

The following day (May 5), security forces surrounded Katumbi’s home and Olivier Kamitatu, a former minister and prominent supporter of Katumbi, reportedly claims an arrest warrant has been issued. Katumbi’s decision has ensured that his life will become very difficult as the Kabila regime dials up its clampdown on its opponents.

Last, there is the question of whether there will even be an election for Katumbi to contest. Elsewhere it might sound silly but in the DRC it is anything but. The Congolese constitution dictates that Kabila must stand down at the end of his second term and hold an election before the end of November 2016. The incumbent, however, has shown no intention of relinquishing power. He is thought to be deliberately delaying the vote until he can introduce a new constitution which permits him to renew his mandate similar to the changes in neighboring Rwanda—but perhaps with less of a popular mandate. Politicians and diplomats privately admit polls in 2016 are an impossibility and the Kabila government appears to favour a lag of several years.

Katumbi has broken cover and faces a long stretch out in the open. More time to build support? Sure. More time avoiding Kabila’s crosshairs? Without doubt.