Ali Bomaye!

One of the most iconic catchphrases in the world of boxing in the Lingala language of central Africa, the chants from an enthusiastic crowd in Kinshasa, host to Muhammad Ali’s championship fight with George Foreman in 1974. It epitomized his connection with Africans. Heralded as not just the world champion but their champion, Ali was a towering inspiration to Africans throughout and beyond his fighting career.

Yet, Ali, born in Louisville, Kentucky and as steeped in American culture and mores as any man of his generation, had a connection with Africa that was deep, meaningful, long-term and way ahead of its time for an African American of his generation.

The love and respect was mutual.

Ali’s popularity on the continent was rooted in his personal struggles and beliefs. Unapologetic about championing his blackness and defiantly embracing his roots, his involvement in the civil rights movement campaigns of the 1960s made him a favorite among Africans who could identify with his causes and struggles.

As disappointment grew in post-colonial Africa, Ali was deified by Africans who felt they were being let down by former anti-colonial heroes turned presidents who had promised so much but given so little. Ali’s strength, defiance and fame across the world as possibly the first global sports star was something Africans could lay claim to.

Muhammad Ali was really the first ‘African’ American. At a time when being called negro was still acceptable, being identified as ’colored’ was polite and being referred to as black was progressive, Ali went that step further and said himself: “I am an African.”

Beyond being adored by hundreds of millions on the continent, Ali championed Africa’s cause, pushing pan-African rhetoric that sought to change the grim views held by many outside the continent long before it became fashionable. “I am glad to tell our people that there are more things to be seen in Africa than lions and elephants,” he said upon arrival in Ghana—his first visit to Africa—in 1964. “They never told us about your beautiful flowers, magnificent hotels, beautiful houses, beaches, great hospitals, schools, and universities.”

That debut tour of Africa, which took in Ghana, Nigeria and Egypt, was a seismic event across the continent as thousands were on hand to welcome him at airports and even more lined the street to catch a glimpse of the great man.

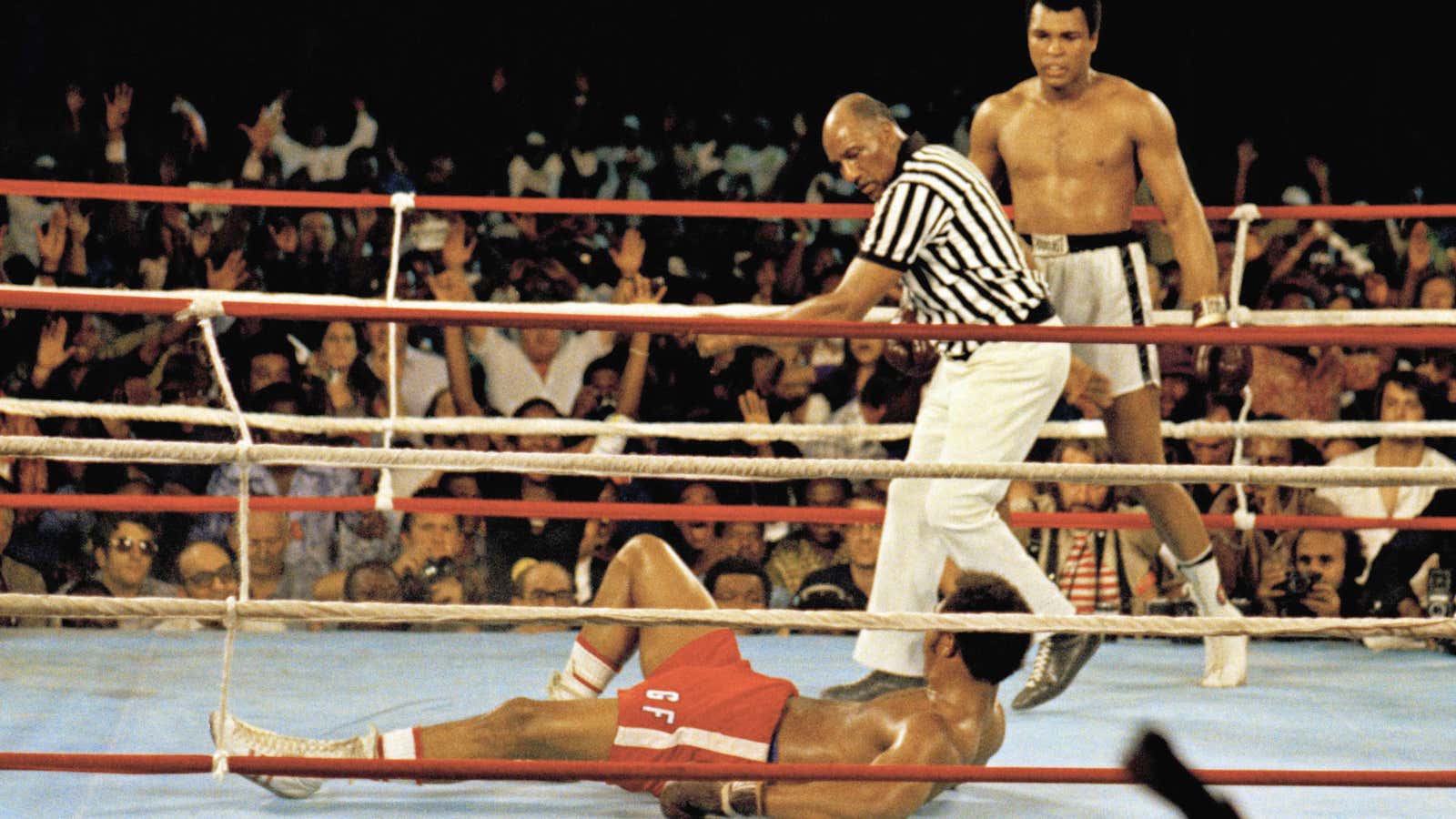

Ali’s connection to Africa was cemented with the Rumble in the Jungle fight against George Foreman in 1974. Hosted by president Mobutu Sese Seko, at the Tata-Raphael stadium in Kinshasa, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo after Sese Seko was overthrown in 1997), the fight was a significant event as Africa got a front-row seat for one of the most defining moments of Ali’s career—and life.

Ali regained his heavyweight title in front of an audience of 60,000 people but the fight reverberated across millions of the people on the continent. Often described as one of the greatest sporting events of the 20th century, the fight put Kinshasa and Africa in the spotlight.

In the wake of his death, the Congolese government credits Ali with making the country “visible” by hosting the Don King-promoted fight in Kinshasa. On the streets, it inspired a generation as, for years, boxing rivaled soccer as the preeminent sport in Congo. ”We spent all our youth with Muhammad Ali,” says Martino Kavuala, a former amateur boxer in Congo. “He was the one who shaped us”

It wasn’t just in DR Congo, Africa has produced scores of great boxers inspired by Ali. One such was Ghana’s Azumah Nelson, a former world featherweight and super featherweight champion.

Ali’s connection to Africa was also seen in his impact on one of the continent’s greatest sons, Nelson Mandela. As a former amateur boxer and avid fan, Mandela once described Ali as “the hero of millions of young, black South Africans”.

Across the continent, tributes have poured in for the legendary champ led by sportsmen, inspired by his achievements in the ring, presidents and elder statesmen, keen to remind a young continent of the indelible mark Ali left on Africa. Ghana’s president John Mahama shared a picture of Ali with Ghana’s first president and renowned pan-Africanist Kwame Nkrumah. African Union chairperson Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, also tweeted condolences.

Ali’s interest in Africa did not end with Kinshasa and he visited the continent several times afterwards. In 1980 in the run-up to the Moscow Olympics US president Jimmy Carter deployed Ali to try and convince African countries to boycott the games after the Soviet’s invasion of Afghanistan.

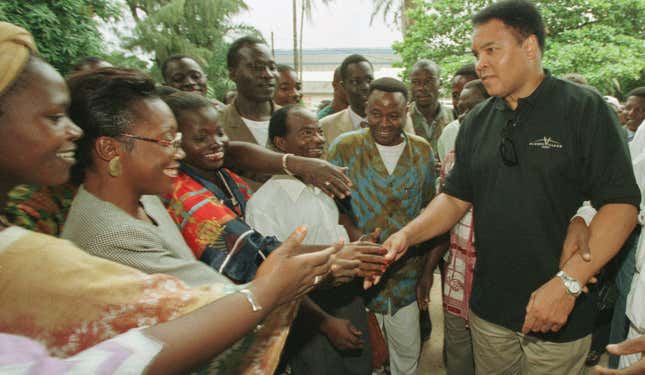

In 1997, he visited Ivory Coast on a goodwill visit to deliver food to 400 orphans in San Pedro, Ivory Coast along the Liberian border where tens of thousands of refugees who fled Liberia’s civil war were living. The story goes that the plight of the orphans came to Ali’s attention when a nun caring for the children wrote a letter asking for his help. Despite already obviously being impacted by the ravages of Parkinson’s disease by then he still flew 7,000 miles to support the children.

In many ways, it feels like Africa itself lost a great son almost as much as the United States did.