There are suggestions that the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa lost the plot after the ascension of Jacob Zuma as the party’s president in 2007. There may be important elements of truth in this. However, there are compelling reasons that situate the morality challenges faced by the ANC – and by extension the country – in the 1994 political transition.

Recent developments do indeed place Zuma, who is now also the president of the country, at the center of the web of corruption at the present time—notably the court ruling in June that Zuma must face 783 corruption charges that prosecutors dropped in 2009. And it is clear that some within the ANC hold him personally responsible for the drastic decay in the party’s morality. For many, the present battle between Zuma and his minister of finance Pravin Gordhan is viewed as the culmination of between those who view the ANC as a machinery for accumulation and those who hold true to its historical mission as a vehicle of liberation fighting for a more socially just society.

The harassment suffered by Gordhan at the hands of the Hawks, an elite police unit, is seen as an extension of the “state capture” agenda that led to the firing of Nhlanhla Nene in December 2015. This comes after a host of allegations that the country’s key state owned enterprises, like South African Airways and the power utility Eskom, have been captured by the Zuma faction of the ANC elite.

This might look like a factional battle with good guys on one side and bad guys on the other. But I would argue that the challenge of economic transformation within a racially polarized capitalist economy provided opportunities for careerism, personal enrichment and corruption.

At the heart of the morality problems faced by the ANC are fundamental forms of relations it has carved with capital as driven by two principal factors.

Firstly, as a political party the ANC has needed funding. Secondly, there is the factor of how the ANC has chosen to promote what it terms the National Democratic Revolution, most notably through Black Economic Empowerment.

Partner with large scale capital

In the mid-1980s, South African capitalism had begun to lose faith in the capacity of the National Party government to stem the rising tide of revolution. Increasingly, therefore, business looked for an accommodation with the ANC. For its part, the ANC leadership recognized the unreality of strategy premised on a revolutionary seizure of power. It presented itself as a partner with which large scale capital could play.

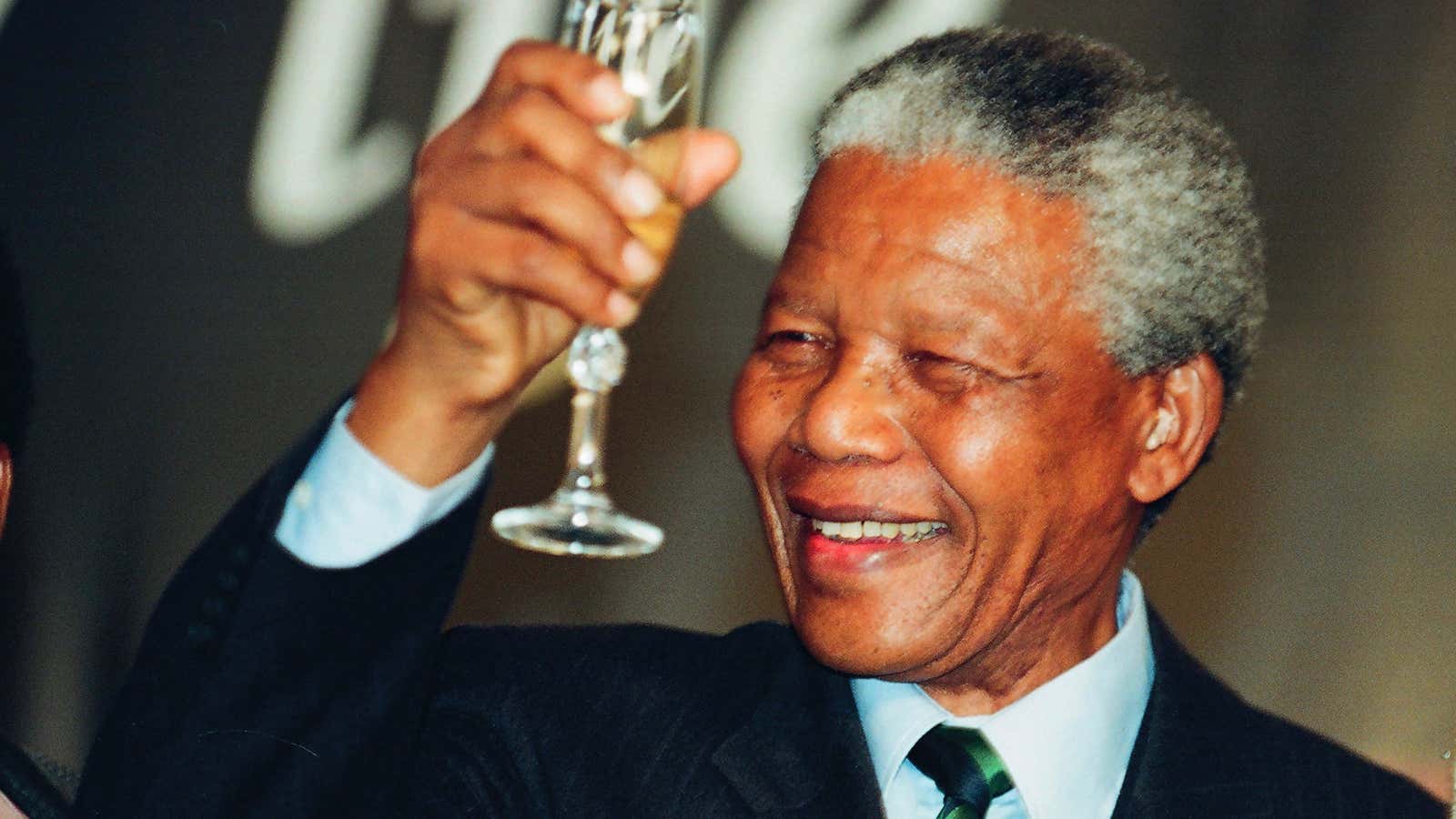

While it was the political negotiation process which grabbed the attention, much was happening behind the scenes. Individuals at the top of the corporate ladder struck up relationships with the incoming ANC leadership. Above all, this was exemplified by a focus on Nelson Mandela, who after his release from jail came to enjoy the company of the very rich. He forged strong relationships with both Harry Oppenheimer, Chairman of Anglo-American, and Clive Menell, vice chairman of the rival Anglo-Vaal mining group.

Just as the ANC was unable to overthrow the political, so it was unable to overturn the economic order. The collapse of the Soviet Union, one of the ANC’s principal supporters, fundamentally changed the international landscape. This played to the strengths of those leaders within the ANC who were less than enamored with state socialism. Such factors, along with pressure from bodies like the International Monetary Fund, underlay the shift away from the left.

State-owned enterprises

At base, the ANC was a nationalist movement whose principal focus was on the capture of the state and the pursuit of democracy. Within this formula was embedded the commitment to the overthrow of “internal colonialism” (the domination of whites over the majority black population). It followed that capture of the state and internal decolonization would require the rapid growth of the black middle class and indeed, the expansion of a class of black capitalists. This was true both in terms of social justice and the needs of the economy.

However, the problem facing an emergent black capitalist class was its lack of capital and capitalist expertise. One of the solutions was that, from the moment it moved into office, the ANC viewed its control over the civil service and parastatals as the instrument for extending its control “over the commanding heights of the economy”. Parastatals accounted for around 15% of GDP.

This included the strategy of transferring state-owned enterprises on discounted terms to blacks via privatization. In the event, this did not prove to be particularly successful simply because the amounts of capital required for the purchase of all but non-core assets were too large for aspirant black capitalists to raise.

Nonetheless, the national democratic revolution charged the ANC with using state power to deracialize the economy. This predisposed the ANC to regard the parastatals as “sites of transformation”. The ANC’s control of the state machinery became a source of tenders for its cadres. This aspect has lent itself to corruption, patronage and the monetarization of relationships within the ANC.

The extent of corruption in tendering is difficult to estimate. The ANC is appropriately anti-corruption in its official stance, and indeed has put in place important legislation and mechanisms to control malfeasance. Equally, however, it has proved reluctant to undertake inquiries which could prove embarrassing.

There have also been two other activities at work. First, certain corporations have distributed financial largess to secure contracts and favor from government. (Their success in so doing is hard to prove given the secrecy of party funding). Second, ANC politicians at all levels of government have sought to influence the tender process in their favor.

Odd combination of power and money

One of the key challenges is that the South African political economy continues to revolve around “an odd combination of new (political) power without money and old money without power”. Each needs the other to advance its interests. This is structurally disposed to favor corruption, as is indicated by the incestuous relationship which has developed between Chancellor House and parastatals. Chancellor House is listed as a charitable trust designed to facilitate economic transformation. However it has become clear that its intent is to fund the ANC.

And the need for party funding is more likely to increase than diminish. Although the case for public disclosure of private funding of political parties is by no means so strong as its supporters proclaim, it remains difficult to exclude influence peddling from this particular terrain.

As the ANC acknowledges, it is a multi-class movement composed of capitalists, middle class, workers and the poor. As such it is a host to class struggle within a society imbued with capitalist values and consumerist temptations. Despite the early efforts of Congress of South African Trade Unions and the South African Community Party to shift policy to the left, many within their own ranks have fallen victim to the temptation of following a political path to personal enrichment. In such a situation, it is not surprising that it is the rich and the powerful who have benefited overwhelmingly from our democracy.

This article was adapted from a paper titled The ANC for Sale? Money, Morality & Business in South Africa published in the Review of African Political Economy. It was originally published on The Conversation.