At night, Feyisa Lilesa and his friends hid in the farms to evade the security forces who were arresting people across the country. As a 15-year-old growing up in Oromia region, Lilesa says he was always aware that many of his fellow citizens didn’t approve of the government’s treatment.

But the moment of awakening for him came in the days and weeks following the landmark May 2005 elections. Championed by the government as a genuine exercise in competitive elections, the vote involved multiple parties, not to mention the significantly enlarged space for political campaigning.

However, when the early outcome of the vote showed a huge lead from opposition groups, the government delayed finalizing the count and responded to protests with a heavy-handed approach. An independent study of the post-election violence by an Ethiopian judge showed the shooting, beating and strangling of almost 200 people, including 40 teenagers. The government also arbitrarily arrested protesters, with police records showing the detention of 20,000 people during the anti-government protests.

When Oromo citizens started demanding justice and demonstrating in Lilesa’s hometown in Jeldu district, the police came to arrest them en masse. Lilesa said that during the day they could be careful about their movements, but at night, under the cloak of the dark, they would go hiding among the unharvested crops.

“This all made an impression on me,” Lilesa told Quartz. “I realized no one was safe.”

On Aug. 21, on the last day of the 2016 Rio Olympics, Lilesa took the memory of those frightful teenage days on to the world stage. Inching closer towards the finish line, with his silver-medal win guaranteed and millions of people watching the televised 26.2 mile-race, Lilesa raised his arms and crossed them in an X, a gesture of solidarity with his people’s protest against Ethiopia’s government.

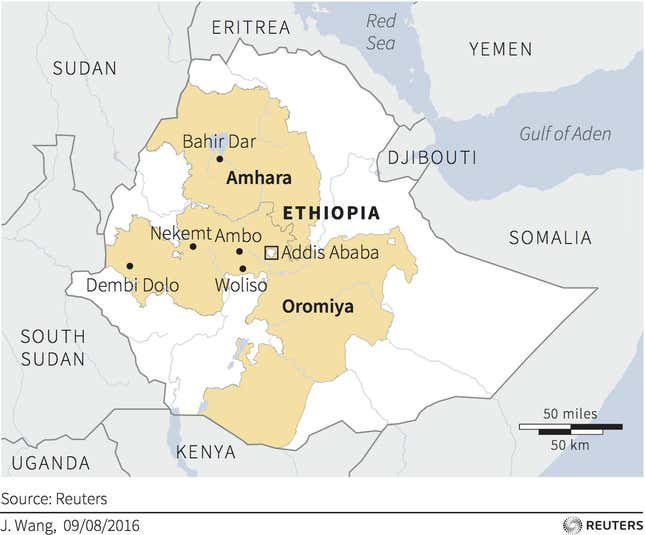

“I had flashbacks of the enormous tragedy happening back home,” Lilesa said of that decisive moment. That tragedy had especially been unfolding since Nov. 2015, when the Ethiopian government started cracking down on Oromo and Amhara protestors, killing more than 500 people according to human rights organizations. “Thoughts about the suffering of my people flooded into my mind,” Lilesa said, and that “strengthened my resolve.”

With that single act, Lilesa defied Ethiopia’s government and used his moment of glory—his first Olympics participation and win – to echo the demands of his people for full political and economic rights. At 26 years of age, and one of the fastest people in the world, he joined a special league of sportspeople who used their platform at the Olympics to perform audacious acts of political and human rights activism.

These athletes included the likes of Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who raised their fists at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City to protest against black discrimination in the United States. Or Jesse Owens, who defied Adolf Hitler at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, and shattered the myth of Aryan supremacy by winning four gold medals.

Lilesa says he didn’t know about Carlos and Smith’s gesture at the Olympics until a day after his protest. He, however, had thought about his defiant gesture and knew the impact his privileged position would generate across the world.

“You don’t raise your grievances in the darkness or in a quiet place,” he said. “Sports gives you a platform, an opportunity to be heard if people are being ignored elsewhere.”

Humble beginnings:

Feyisa Lilesa was born in the West Shewa district in Oromia to a family of farmers in 1990. The second of seven children, he grew up helping his parents around the household, taking care of the livestock and carrying goods to the market. With no electricity or television at home, running for him equated to racing to school and not a way to make a living. When he was in fourth grade, he learned that some people pursued running as a career.

Just as Lilesa was learning to get competitive and expand his horizon, Ethiopia was also undergoing a transformation. Shortly after he was born, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front defeated the Derg military regime led by Mengistu Haile Mariam.

Under the leadership of late prime minister Meles Zenawi, Ethiopia experienced significant economic growth, and the unveiling of key energy and infrastructural projects. The government, populated by the minority Tigray community, also extended a tight grip over politics, banning opposition parties, jailing its leaders and supporters, and muzzling the free press.

When the government introduced a master plan last November to integrate the capital Addis Ababa with the neighboring Oromia region, protests broke out across the region. The Oromo community argued that, if implemented, the plan would work to cleanse their culture and identity from their region.The government canceled the plan in Jan. 2016 after 140 people died—but the unrest continues to dog Ethiopia.

For Lilesa, the government’s tight leash eventually hit close to home when his brother-in-law was arrested. The turbulence in the country also coincided with his training for the Olympics, an ambition he harbored since he won his debut race at the 2009 Dublin Marathon, aged 19. Given the repressive conditions in the country, Lilesa said he couldn’t discuss, even with his running mates, his feelings about the crackdown. So he decided to avert attention, train harder and hope that the Ethiopian Olympic Committee would select him to go to Rio.

‘Big fuss out of nothing’:

When Lilesa crossed the finish line in Rio, Ethiopia’s state broadcaster didn’t show the video of his protest. Getachew Reda, the country’s communications minister, promised to welcome Lilesa back home as a “hero,” saying nothing was going to happen to him. Initially, Lilesa’s family were also “shocked because they didn’t want to lose me,” he says. His wife, who he met in school, and his two children, all live in the capital Addis Ababa.

Lilesa says he wanted to sacrifice everything—his career, his status, the possibility of never reuniting with his family—for the sake of his children. He wanted them to grow up in a changed Ethiopia, and he wanted to be part of that change. “I love my country. I don’t want to leave it. I want to help change it so that people can live in peace.”

After staying in Brazil for two weeks, the United States government granted him a special skills visa that allowed him to come to the US. And on Sept. 13, two days after the Ethiopian New Year, Lilesa addressed his first news conference in front of the US Capitol building, flanked by congressmen, supporters, and the media. He didn’t want to seek asylum in America, he said, and he wanted to get back to competitive sports as soon as possible. Wearing a slick dark suit and white shirt, and sporting his signature afro hair, the long-distance runner called for the world to turn its attention towards Ethiopia.

“I want the superiority of one ethnic group to end,” Lilesa told Al Jazeera English. “If everyone does not have equal power, their different political, religious views respected, in the future, there will not be sustainable peace in the country.”

For now, Lilesa says he has no plans of ever going back to Ethiopia until there’s a regime change.

“No other country would be as comfortable for me as the beautiful place of my birth. Nowhere measures up to it,” he told Quartz. But what Ethiopia is lacking, he said, was “visionary leadership that can garner and develop the resources for the benefit of all, not just a limited few elites who take all for themselves.”