Johannesburg

Just as Freedom Park, south of Johannesburg, completed its transition from a shanty town to a lower middle class neighborhood with electricity, piped water, and tarred roads; a spanking new Shoprite store opened up in November, with its distinct bright red and white logo and brand livery.

This strategy to seek out Africa’s growing middle class consumers, in places its competitors have yet dared to venture, has helped drive Shoprite’s rapid expansion in the last decade. The food retailer has expanded from eight poorly performing stores worth 1 million rand in 1979 (around $1.2 million then), to become Africa’s largest retail chain, worth 113.7 billion rand ($8.5 billion) today.

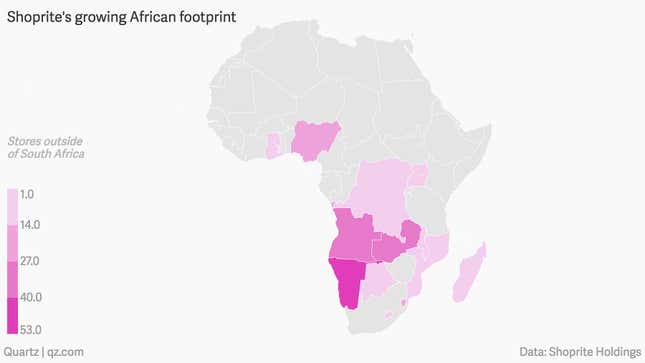

Shoprite’s mushrooming from a corner in South Africa’s Cape to 2,214 stores (and counting) in countries across the continent was led by longtime CEO James Wellwood Basson, known everywhere as Whitey (a childhood nickname on account of his pale blond, now gray hair, that has stuck despite South Africa’s racial issues). Basson is a big personality with an even bigger paycheck whose sheer determination took Shoprite across Africa, while the group’s competitors took too long to realize the continent’s retail potential, or just used the wrong strategy.

He’s dismissed criticisms on low wages for his workers with the argument that he is creating jobs, and has been known to use local expletives in general meetings. It’s all forgiven as Shoprite’s charts consistently climb.

Now aged 70, the local retail celebrity announced his plans to step down after nearly four decades, leaving questions about where Shoprite would venture next. His successor will be Pieter Engelbrecht, a 20-year Shoprite veteran who was once Basson’s assistant.

The low-cost grocer’s slogan promises “low prices for you,” and it has been able to keep that promise in South Africa where other retailers are struggling. It diversified its customer base by launching the less expensive USave format store, described by the group as an “ideal vehicle for the group’s expansion into Africa and allows far greater penetration into previously under-served communities in South Africa.” Then there’s also the higher-brow Checkers, aimed at upwardly mobile customers interested in ready-to-eat meals and a good wine selection. (The South African chain is not related to the US franchise ShopRite).

Outside of South Africa, Shoprite and its affiliate stores are not necessarily low-cost, but they do offer a variety and an aspirational sophistication that local retailers and informal street markets simply can’t compete with, especially on shelf life. Among Africa’s growing middle class, going to Shoprite has become something of an outing for young families climbing the economic ladder in cities like Lagos or Accra. Heading to Shoprite doesn’t just mean filling your trolley with the month’s groceries, it’s going to the mall to grab a pizza or see a movie, giving consumers a reason to choose the South African brand over local rivals.

“It’s a much more competitive environment,” said Sasha Naryskine, an analyst with Vestact. Rather than simply export a South African product into Africa, Shoprite understands that consumer behavior differs from state to state in each country and they’ve made sure their products, especially canned and packaged goods, match those tastes. “Shoprite has understood this, but also by selling to value-orientated consumers who want to get all their goods in one place with a longer shelf-life.”

Crucially, Shoprite has also exported South Africa’s fondness for malls, thereby overcoming infrastructural challenges in building its own centers. It often partners with local property developers. This is especially important in African countries where the retail markets are not as developed as South Africa’s.

For example, in Kano, northern Nigeria, a Shoprite store is part of an $85 million retail investment trying to modernize the historical African trading city. In Angola, where Shoprite has had a bumper year despite a difficult economy , it has partnered with Debonairs Pizza, a South African chain, making the Shoprite center more than just a grocer, but a place to hang out.

Shoprite took its pioneering, centralized distribution chain to the rest of the continent, which allows the group greater control of logistics in working with both multinational suppliers and local farmers.

“They had faith in Africa and South Africa, whereas others didn’t have the same faith in the African economic story,” says Andile Ntingi, an analyst with GetBiz. “That faith has paid off.”

While other South African chains crashed and burned in countries like Australia, or misapplied the high-end model to Africa, Shoprite stuck to a simple yet effective strategy, he said. And it was smart enough to invest in commodity-rich countries where the consumer base was bound to grow, he adds.

Basson expanded Shoprite into Africa long before it was cool. The expansion was fast and aggressive, often through local acquisitions. Basson opened the first store outside South Africa in 1990, just as neighboring Namibia gained independence. Zambia and Mozambique followed in the mid-1990s. During this time Shoprite also acquired the OK Bazaar group, converting all their outlets in Swaziland and Botswana to Shoprite, thus cementing their footprint in southern Africa before a rising Africa was seen as a lucrative market. Shoprite Holdings also listed on the Namibian and Zambian stock exchanges in 2002 and 2003, respectively.

It wasn’t an easy sell to the board and investors, according to Christo Wiese, Shoprite’s chairman.

But there were also losses along the way. Shoprite left Egypt after just five years, citing restrictive market conditions. Zimbabwe’s turbulent economy proved too much for Shoprite’s strategy and it closed shop in Bulawayo in 2013. A year later, it threw in the towel in Tanzania, saying the country largely favored market food shopping over a formal retail establishment. Last year, reports surfaced that Shoprite was giving up in Uganda, too, with plans to sell to local rival Nakumatt. But the group denies this and still lists outlets in the country. Shoprite’s ventures beyond the continent did not fare well either, and in 2010, Shoprite sold its only outlet in a Mumbai mall to the Future Group, India’s largest listed shopping chain.

Ironically, Basson’s departure may be linked to what could be Shoprite’s greatest expansion yet. Wiese, who owns a 16% stake in Shoprite and 18% of Steinhoff, has floated the idea of merging Shoprite and Steinhoff since about 2006, according to reports, and the merger chatter won’t go away. Steinhoff is a South African-owned merchandiser with plans to take on IKEA in the United States and Europe, and could take the Shoprite model even further. But, as analyst Naryshkine notes, such a merger and subsequent expansion would expose Shoprite to the kinds of risks it never faced in Africa.

Basson is on record opposing the merger, but by his own admission, he is tired now and just wants to sleep in. And it would be a well-deserved rest. Basson started his career as an accountant but has become a retail maverick, systematically building a solid infrastructure and customer base on a combination of faith and pragmatism that has covered Shoprite across Africa. Its relentless expansion is unlikely to slow and remains undeterred by its setbacks.