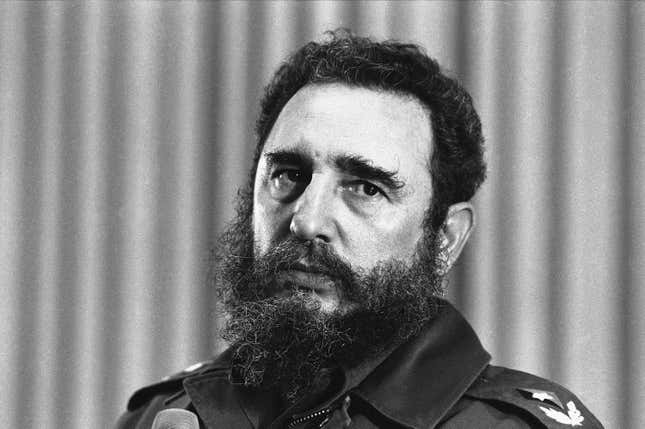

In southern Africa, Fidel Castro is almost universally seen as a hero. After all it is the Cuban leader who sent his forces to Angola to halt apartheid South Africa. What southern Africans would easily forget is that Cuban troops were sent to many other African conflicts with mixed results.

Professor Piero Gleijeses, who chronicled Cuba’s relations with Africa, noted:

The dispatch of 36,000 Cuban soldiers to Angola from November 1975 to April 1976 stunned the world and ushered in a period of large-scale operations, including 16,000 Cuban soldiers in Ethiopia in late 1977; Cuban military missions in Congo Brazzaville, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Benin; and, above all, the continuing presence in Angola that peaked in 1988 with 52,000 soldiers.

In Somalia and Ethiopia Castro’s record gets a distinctly mixed reception. The headline on one popular website said it all:

Ethiopians celebrate Castro, Somalis fume at him over 1977 Ogaden war.

The different interpretations stem from how should one regard the Somali invasion of Ethiopia in 1977. Was it an unprovoked attack on a sovereign nation, in violation of the Charter of the United Nations and the Organisation of African Unity? Or was it a brave attempt to reunite the Somali people after they were incorporated into Ethiopia in the nineteenth century by the Emperor Menelik II?

The Greater Somalia dream

General Mohammed Siad Barre seized power in Somalia in 1969. Like many Somalis, he regarded his nation as incorporating a much wider area than the country recognised by the international community. Greater Somalia included Djibouti, Somaliland and the Northern Frontier district of Kenya, as well as Somalia itself.

Siad Barre, aware of the weakness of the Ethiopian state following the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1975, established the West Somali Liberation Front (WSLF). Somali regular troops, supporting WSLF fighters, began attacking Ethiopian forces. In 1977 Ethiopia complained that it was under attack from its eastern neighbour.

At the time, the Soviet Union was supporting both Ethiopia and Somalia. But the attacks forced it to choose between Mogadishu and Addis Ababa. Moscow chose the latter, although it continued to try to mediate between both sides.

In early 1977 Fidel Castro met the Ethiopian leader, Mengistu Haile Mariam and Siad Barre in Aden. But after lengthy negotiations he came down on the side of Ethiopia. As Castro is reported to have told the East German leader, Erich Honecker:

I have made up my mind about Siad Barre, he is above all a chauvinist. Chauvinism is the most important factor in him.

The Cuban leader decided to send troops to support the Ethiopians as Somali forces drove deeper into Ethiopia. In September 1977 the Soviet Union established an air bridge to save the Ethiopians, pouring $1 billion worth of military equipment into the country. At one time a Soviet aircraft was landing in Addis Ababa every 20 minutes. Castro sent 11,600 Cuban troops and more than 6,000 advisers.

The United States, which had backed Ethiopia, switched sides. President Jimmy Carter, deeply worried by the Soviet and Cuban deployment, withdrew support from the Ethiopians, backing Somalia instead. But after divisions within his own administration, Carter refused to send a carrier force to counter the Soviets and Cubans.

The reinforcements did the trick. By March 1978 the Ogaden town of Jijiga had been recaptured by Cuban and Ethiopian troops led by Soviet and Cuban officers. Although the WSLF continued fighting in the Ogaden for several years, the Somali attempt to capture the region was over.

Impact of Cuban intervention remains

If Siad Barre’s dream of a greater Somalia had been crushed, the consequences were not. The Ogaden is still littered with burnt out tanks and armoured cars, a symbol of the geopolitics of the region. Ever since the invasion Ethiopia has regarded Somalia as an enemy, that must be kept weak and divided.

But the impact of the Cuban intervention goes wider still. Castro insisted that his forces should not be involved in Ethiopia’s war against Eritrean liberation movements which had been fighting for the independence of their country since 1961. On 25 November 1977, the day that Castro decided to send troops, he stressed that,

these soldiers are to fight exclusively on the Eastern Front against Somalia’s foreign aggression.

Castro remained true to his word, but having Cuban forces in the Ogaden did allow Ethiopia to transfer troops to the Eritrean front, containing the Eritrean drive for independence.

So what is Castro’s legacy in the Horn of Africa?

Many Ethiopians would regard him as the man who saved their country. Somalis would regard Castro as having prevented the reunion of their nation. Eritreans might consider him a friend, who supported their case for independence, but also as someone who inflicted terrible damage to their cause. It is all a question of perspective.

Martin Plaut, Senior Research Fellow, Horn of Africa and Southern Africa, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.