If South Africa’s non-fiction bestseller list is an indication of the zeitgeist, the country has had an anxious year. The nation’s bookstands reflect a country trying to make sense of a tumultuous political environment, high crime statistics, and an unreliable power grid.

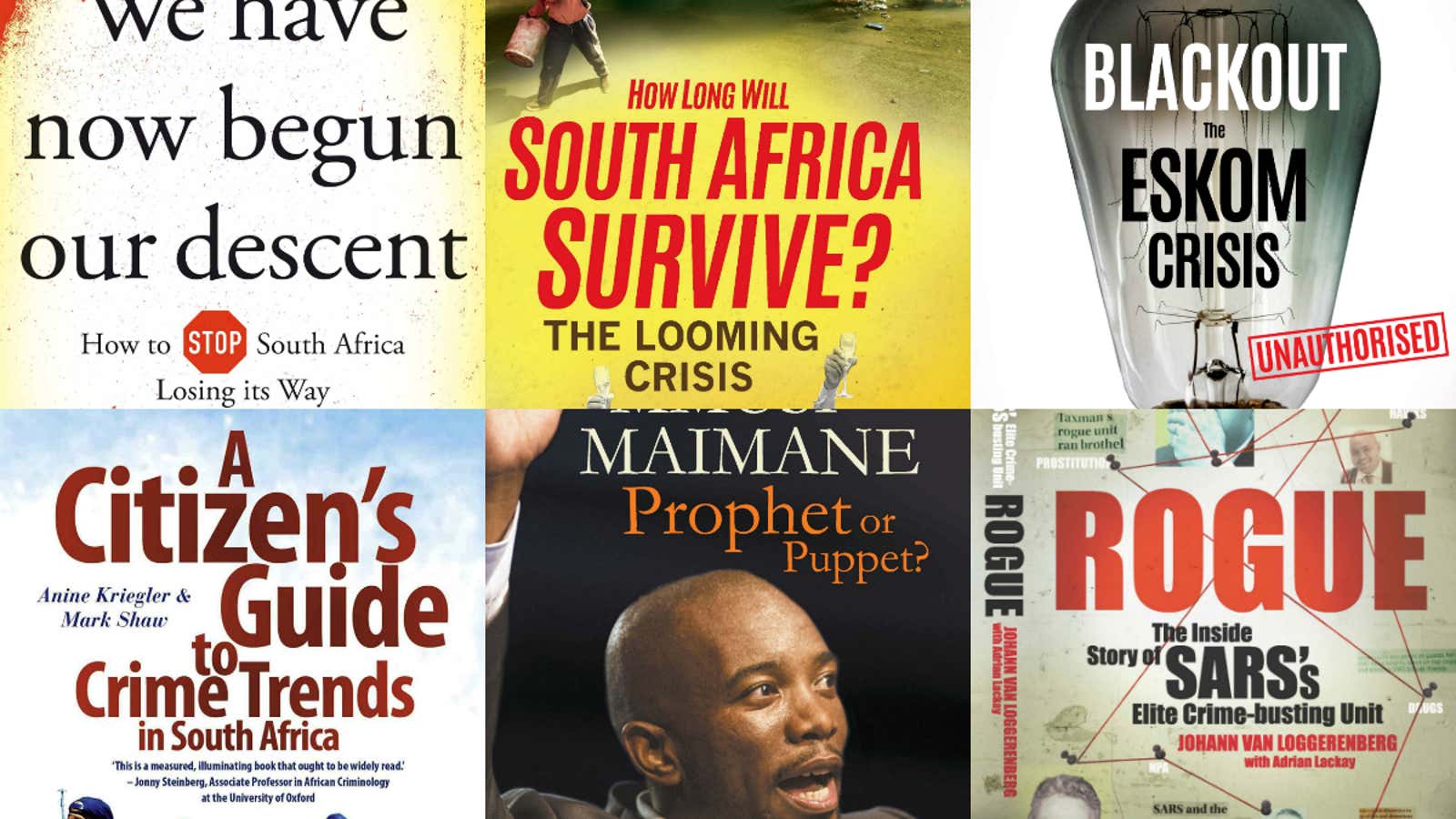

Apocalyptic titles like How Long Will South Africa Survive?: The looming crisis and We Have Now Begun Our Descent have flown off the shelves.

Fears that corruption could overwhelm state institutions have driven readers to non-fiction analysis. A legal document, the Public Protector’s state capture report, made for some of the most explosive reading of the year, as it outlined how the president’s friends were able to interfere in cabinet matters.

With political machinations happening behind the closed doors of party executive meetings and communicated to the public in doublespeak, readers are looking to analysts to weigh in on what the 355-page report means for the country’s future, in titles such as Rogue: The Inside Story of SARS’s Elite Crime-busting Unit.

South Africans are turning to commentators as modern day oracles to divine just how close the country could be to disaster. Another book, Blackout: The Eskom Crisis, looks at why the national power supplier has been beset by rolling blackouts.

“Because of the heightened political conflict in this country, there’s always a lot to be played for by different and opposing views, constituencies,” says Jeremy Borain of Jonathan Ball Publishers. Authors who could make sense of current affairs saw success, he explains.

This mood is likely to prevail in 2017, Borain told Quartz, when the ANC’s elective conference is set to take place. Forecasts of which faction will triumph and who will succeed Jacob Zuma to rule South Africa will make for rich non-fiction.

Zuma, and the controversy around him, is the “gift that keeps on giving,” says Borain. Works about Zuma himself aren’t as likely to sell as books making sense of Zuma’s South Africa and the country he will leave behind.

Books predicting a post-Zuma scenario, When Zuma Goes and #ZuptasMustFall And Other Rants (a play on the president’s name Zuma and his controversial associates the Gupta family) are doing well.

South Africans also are lovers of biographies, and the life stories of athletes, politicians and even a constitutional court justice did well. This is also true of books that promise to reveal the hidden side of a politician or newsmaker.

Overall, South African non-fiction far outsells fiction, explains Borain. Still, it is a small market, so anything that sells above 5,000 copies is considered a success. Rogue, a book about the murky political interference in the South African Revenue Service, has already sold over 25,000 copies since September, said Borain.

Fiction authors, on the other hand, are lucky to sell a few hundred copies, especially when competing with the international fiction market. When South African readers aren’t trying to make sense of their country’s immediate realities, it seems they’re trying to escape it.