On the morning of Dec. 13 2016, the police summoned Maxence Melo, a co-founder of JamiiForums, a popular online platform in Tanzania, and promptly arrested him.

Melo spent a week in jail. He was later charged with obstruction of justice for refusing to divulge JamiiForums user data and operating a website not registered in Tanzania.

The incident sparked debate once again about Tanzania’s controversial cybercrime law. Passed in 2015 during the Kikwete administration, the law has seemingly spent more time policing speech than prosecuting cyber criminals. The law contains vague clauses that are being used to restrict freedom of speech. This includes prohibiting publication of “false” and “misleading” information. The law gives the police wide-ranging powers to seize communications devices.

But Melo’s arrest is part of a pattern of government behavior that is looking less and less democratic, with the state aggressively asserting its control over the political, economic and social life of the country. Prosecutions to date include eight volunteers for opposition party Chadema. The volunteers’ alleged offence was sharing election results data over Whatsapp deemed by the government to be inaccurate.

Smaller margins

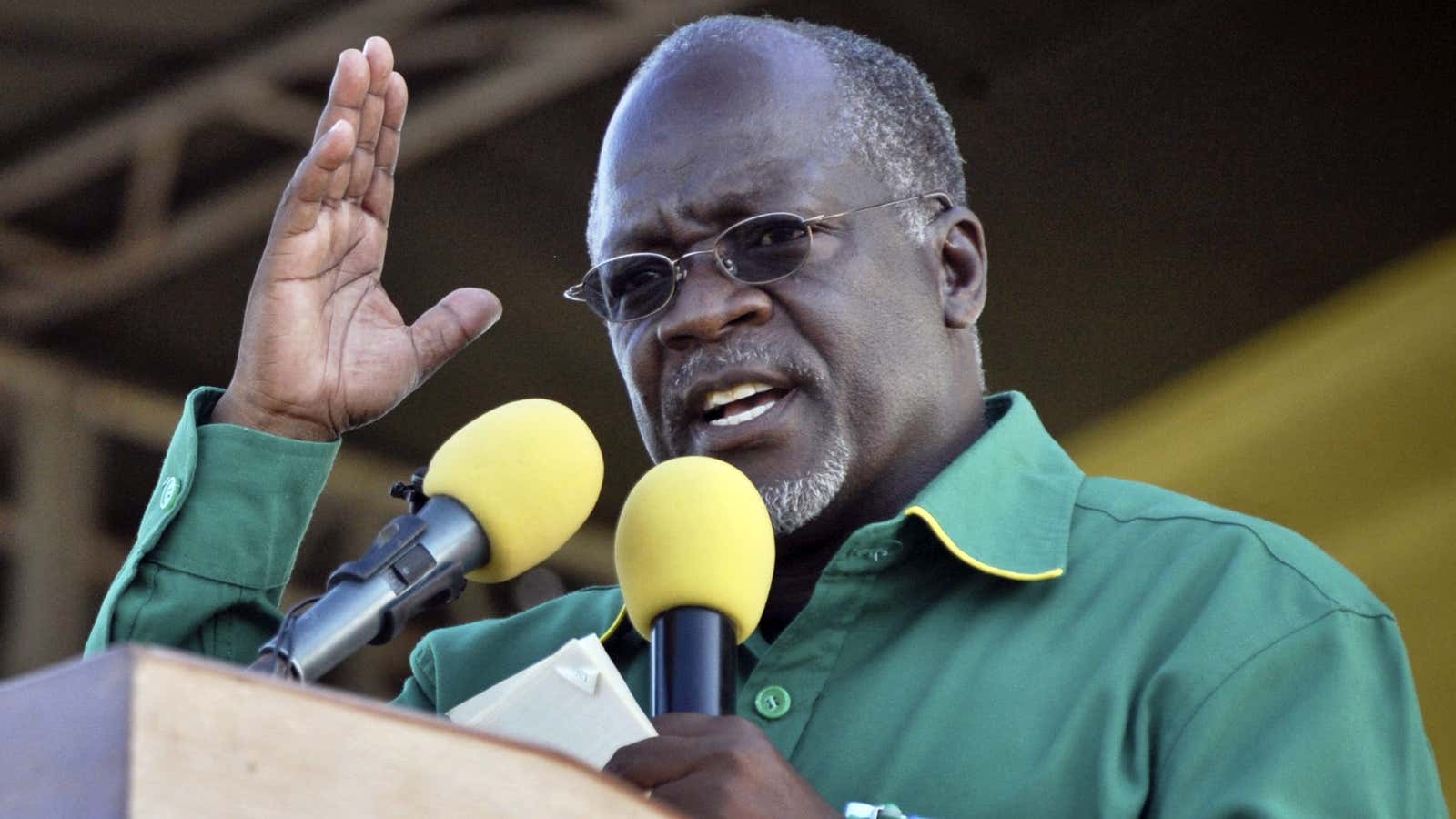

For a while now, some figures within the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party have been worried about eroding support among voters. The party which has been in power since independence, first raised internal concerns in 2010 after then president Jakaya Kikwete was re-elected with 20% less votes than in the previous campaign. They blamed the opening up of the political and media space as being behind the party’s decline in popularity. This fear became even more pronounced after the 2015 election, when current president John Magufuli won office with 58% of the vote, the lowest share won by a CCM candidate since independence.

This may explain why since Magufuli has come to power, his government has taken significant steps to manage debate and criticism of its conduct.

In addition to the cybercrime and statistics bills, the government recently passed a media bill that Aidan Eyakuze, executive director of Twaweza, a civil society organization, called “a clear and present danger to the independence of Tanzania’s media, to our collective struggle against corruption and to our young democracy.”

This effort to limit public discourse began soon after Magufuli came to power. In Jan. 2016, the information minister stopped the regular live broadcast of parliamentary proceedings. Apparently keeping in line with the president’s popular drive to cut government waste, the minister said the broadcast production was too expensive. But independent bodies have offered to foot the bill and the government has still refused to change course.

Over the years, the raucous debate in Bunge, as parliament is known in Tanzania, has led to the uncovering of high profile scandals, embarrassing the government of the day in the process. In fact, polls show a lot of Tanzanians watch and listen to the proceedings and it helps shape their political views. So the decision to stop airing the sessions was seen by some as an attempt to limit people’s access to views critical of government.

This was followed in June by Magufuli’s ban of public rallies by the opposition. The election was over, the president said, and that the opposition should stop distracting people. “We can’t allow people to politicize each and everything, every day,” Magufuli said.

A month later he suggested external forces may be behind such protests. They were trying to destabilize the country so they can get a hold of Tanzania’s resources, he claimed. “They (imperialists) will come with a lot of words, such as democracy. Do they even have democracy in their own countries? Our democracy is enough, let’s defend it and live peacefully,” Magufuli said.

Then there has been the arbitrary sackings of public officials in the name of corruption and incompetence. Yet, the two most recent high profile firings have been done with little or no explanation as to why they were let go, with analysts suggesting that it once again demonstrates the president’s intolerance of dissenting views.

All these actions show a leader wanting to centralize power within government. In turn, it has created an atmosphere of fear amongst people whether they be in government, media or as private citizens.

“Everybody is scared, thinking he is going to come after them,” Erick Kabendera, an investigative journalist, told Quartz. “He is taking the country back to the days of socialism where people believed [founding president] Nyerere was listening to everything, even at your house, people believed he was there listening.”

He adds, “It’s shocking for an aspiring, progressive democracy.”

For the moment, Magufuli remains popular, despite a difficult economic environment.

But a recent survey showed there may a softness to his support. Only 43% of rural Tanzanians, the bedrock of Magufuli’s support, say the country is better off since he assumed power. The question is how patient voters will remain if he struggles to deliver on his promises, while at the same time continues to stifle the democratic space.

“Ultimately, such a muscular approach may be alienating citizens from their own government and precluding an open sharing of ideas for tackling our myriad challenges,” Eyakuze says.