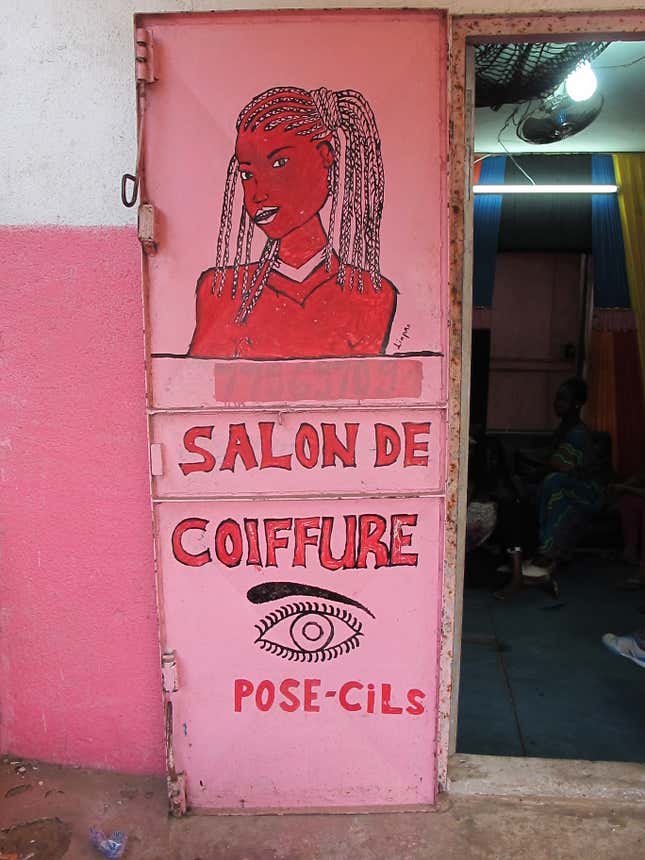

I am huddled in a small vibrantly decorated salon in the West African city of Dakar, the capital of Senegal. The walls are draped with folds of colored cloth—red, orange, purple, pink, blue, black and yellow. Seated in front of the mirror on the only chair is a woman in a full-length brightly colored dress of richly patterned, intricately tailored cloth.

Leaning over her, Tata, the stylist, is winding and stitching down thick coils of twisted black synthetic hair streaked with golden-brown to create a high basket-like formation built around a cushioned bun of fibre beneath.

The client is getting ready for her niece’s baptism and is expected to convey an air of formality for this important all-day event. She has left the exact choice of style to Tata, who keeps a repertoire of possibilities on her smartphone and who adapts ideas from magazines, TV shows and what she sees at functions and in the streets.

Photos of some of the more extravagant styles she has created adorn one of the mirrors in the salon. The client’s own chemically relaxed hair is scraped up under the coiled structure and plastered down with gleaming black gel which will dry to hold the style in place. Tata works with a comb with a pointed metal end, an implement resembling a multi-headed toothbrush, a needle and thread and large volumes of locally manufactured synthetic hair fibers, some of which dangle from the back of the chair.

To create a tidy finish Tata lights a splint and uses the flame to singe off errant fibres. Clearly the chemical composition of hair products has improved since the days when Michael Jackson’s head caught fire during the filming of a Pepsi commercial, allegedly owing to the flammability of the pomade in his hair.

There are three companies with factories in Dakar that manufacture the synthetic hair fibre known as Kanekalon, the oldest of which is Darling Hair. Though owned by a Lebanese businessman, supervised by Koreans and using a chemical formula developed by the Japanese, Darling Hair is nowadays considered a local African product, made both in Senegal and in Kenya.

Packs of synthetic fibre can be seen stacked and hanging in shops and market stalls not just in the capital but in towns and villages all over the country. They sell for around 1,500 west African francs (£1.75) per pack. The fibre is also exported to other African countries and to America. It comes in a variety of models and is ideal for braiding into a plethora of styles as well as for use in synthetic hair extensions.

At the back of Tata’s salon, a group of women are seated on a sofa, busy braiding Kanekalon fibre into the short Afro-textured hair of a young woman sitting on the floor in front of them. She has been there since morning and is looking restless. There were four women at work on her head when I arrived in the salon, and three are still at it when I finally leave as darkness approaches. They are making twists, using two tresses of fibre at a time as opposed to plaits, which require three.

The atmosphere is friendly and relaxed. Small children run in and out of the salon and when friends pass by they join in the braiding. It is a skill learned in childhood and practiced on many a doorstep. The Senegalese twist, as it is called, is currently a fashionable black style option internationally. The internet abounds with speeded-up videos of women making Senegalese twists in bedrooms from Dakar and Paris to Los Angeles and Kingston. Hair and hands work together to create fantastic effects that vary according to the length, width and color of the fibers and the patterns into which they are arranged on the head.

But the Senegalese have not only invented a regional style of twisting hair; they have also added a new twist to the understanding of what is meant by ‘natural hair.’ In Dakar, when women refer to cheveux naturels they are referring not to their own hair in its natural state but to the much-coveted human hair that has become available for purchase in the last five or six years, albeit at astronomical prices.

It is difficult to imagine an idea of natural hair more contrary to that promoted by the natural hair movement in America and Europe. ‘Cheveux naturels is a huge luxury. It costs more than a person’s salary but some women just will not be happy until they obtain it,’ a young professional woman called Muza tells me, adding that if she had that amount of money she would rather spend it on getting a new computer or something helpful to her progress in life.

But Muza is the exception. ‘Some women just don’t consider themselves beautiful without it. It’s a fashion statement and a status symbol. It means they are part of a particular trendy set.’ It is a theme I hear recurrently as I discuss cheveux naturels with Senegalese women.

‘How can people afford it?’ I ask repeatedly when they tell me it costs between 150,000 and 300,000 francs (£175–£350), which is three or four times the average monthly salary in Senegal for low-skilled work. The answers are suggestive. ‘If a guy wants to seduce a woman then he offers to buy her cheveux naturels. That’s why we have to keep several boyfriends at once, to be sure to persuade one of them to give us hair!’ The young woman laughs as she recounts this but then adds, ‘Some people say it is a form of prostitution in a way.’

‘It is possible to pay for hair in installments spread over several months,’ another woman points out, ‘and some women form circles where they each pay in ten thousand francs a month and one person gets to purchase hair.’

‘We sometimes rent out cheveux naturels for special occasions,’ a stylist tells me. ‘It’s the dream of every Senegalese woman to have it. It makes them more beautiful. Some women feel inferior if they do not have it, so they just keep on begging their husbands every day until finally they relent!’

Whilst all of the women I meet bemoan the disproportionate price of cheveux naturels, most of them seem to covet it. Some have managed to obtain some on the cheap via a brother working in a hair factory in Italy, a cousin in Paris or a trading connection in China. So associated is it with beauty, wealth and success that even those critical of it often seem seduced by its appeal.

‘Have you brought some in your bag?’ three young professional women ask me after criticizing the trend. They are clearly disappointed I have not.

Men, on the other hand, are more overtly opposed to cheveux naturels, which they blame for causing tensions in relationships and even marital break-ups. They accuse women of having misplaced priorities, of putting their desire for hair before the need to feed their families and of a selfish obsession with looking beautiful. Some stress the importance of challenging Euro-American beauty norms by rejecting skin-lightening products and hair extensions.

Yet their attitudes are perhaps more ambiguous than their words suggest. Some men undoubtedly get pleasure from the glamour of being associated with women who wear cheveux naturels and are willing to woo women with the offer of it. As Muza remarks coolly, ‘Men may say they don’t like it and of course they hate the cost but they are attracted to the look of cheveux naturels.’

There are other male voices too—those of imams in a country where 90% of the population is Muslim. These religious leaders sometimes denounce cheveux naturels in their sermons, not only for its cost but also on the grounds that it prevents women from performing ritual ablutions correctly as the water cannot get properly to their heads. ‘Cheveux naturels is completely contrary to Islam,’ one woman tells me over lunch.

‘The imams don’t even like synthetic braids like these.’ What is clear from her own hairstyle and those of other Senegalese women is that where hair is concerned imams’ perspectives are not top priority. Women’s hair is above all a woman’s affair, and Senegalese men readily admit that they often can’t decipher what women are wearing on their heads.

A complex hair culture is not unique to Senegal. It is found in many African countries. It is as if the fact that most Afro hair spirals upwards and outwards rather than downwards has inspired an infinite range of architectural styles.

The aesthetic possibilities this offers have been captured by the legendary art photographer J. D. ’Okhai Ojeikere. Fascinated by the complexity, diversity and structural ingenuity of Nigerian hair, he set about photographing almost a thousand styles popular in the 1960s and 1970s. His beautiful black-and-white portraits are an extraordinary testimony to the artistry involved in building hair into complex geometric patterns and forms, many of which were associated with particular political moments, moods, proverbs and events.

Such styles often involved the addition of extra fibers—usually animal or cotton—which were sometimes twisted around frames made of pliable sticks. Like so much cultural activity, these hair styles seemed to demonstrate not so much the love of the natural as the capacity to transcend it.

Excerpted from ENTANGLEMENT: The Secret Life of Hair by Emma Tarlo. Copyright © 2016 by Emma Tarlo (Oneworld Publications.)