“God bless Africa.” The title and first lines of Enoch Sontonga’s hymn Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika may appear simple to some. But 120 years after it was written, it has become one of the most powerful tunes in Africa’s history, a symbol of the post-colonial liberation movement used in the past and present post-independence national anthems of South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Namibia.

Sontonga’s contribution to African unity was honored today with an illustration showing the prodigious poet and composer in a blue suit and top hat, surrounded by a swirling stanza on google.co.za. The image commemorates South Africa’s national Freedom Day, a public holiday marking the first time democratic elections were held on April 27, 1994.

Sontonga, a teacher, initially wrote the Xhosa hymn for his school choir in 1897, and is believed to have been inspired in part by the work of Welsh poet Joseph Parry. The hymn became popular over time as it was performed by other choirs. In 1912, it was sung at a meeting of the South African Native National Congress, now known as the African National Congress. The ANC adopted the hymn as its official song in 1925, singing it in defiance of the South African government’s racist, restrictive policies towards black Africans. It would go on to become a unifying pan-African liberation anthem, buoyed by its banning by the apartheid government.

In 1994, at then-president Nelson Mandela’s request, a modified version of Sontonga’s hymn was combined with the previous Afrikaans national anthem, Die Stem van Suid Afrika (The Call of South Africa), and lines in several of South Africa’s other official languages, to form South Africa’s current national anthem.

“Composed in the form of a blessing, the hymn offers a message of unity and uplift and an exhortation to act morally and spiritually on behalf of the entire African continent,” David Coplan and Bennetta Jules-Rosette wrote about the song’s role (pdf). It was “an emblem of hope and unity.”

Sontonga’s hymn changed over time as its lines were modified, added to, and translated into other languages—each revision reinforcing its powerful symbolism. These changes presented ”different versions of a virtual Africa yet to be born,” Coplan and Jules-Rosette explain. “Emerging out of a profound sense of discontent with a social world in which the creative process of self-definition and re-definition was forcibly denied, all the transmutations of Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika… conclude with the hope for change.”

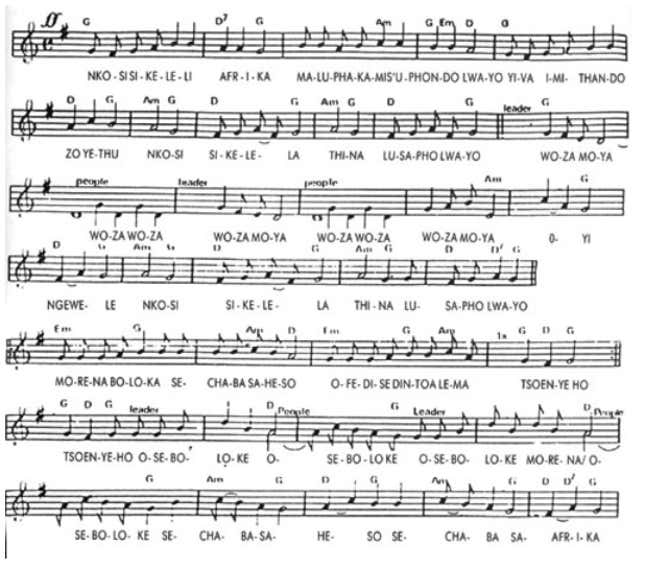

You can read Sontonga’s original verses here, while the full version of the South African national anthem appears below.