This story was produced through a partnership between Quartz and Climate Central, a non-advocacy science and news group, with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

As the effects of heat-trapping pollution continue to raise sea levels, wetlands dotting American coastlines could drown — or they could flourish. Their fate will depend upon rates of sea-level rise, how quickly the plants can grow, and whether there’s space inland into which they can migrate.

Climate Central modeled how American coastal wetlands will respond to sea level rise in an array of potential scenarios. It found that conserving land for wetlands to migrate into is a decisive factor in whether wetlands will survive or drown.

Wetlands and development have long been in conflict, with ecological values weighed against waterfront economic opportunities. As seas rise, benefits of conserving areas inland for wetland migration are creating new tensions. And as climate change intensifies storms and elevate high tides and storm surges, the economic values of wetlands are growing.

How fast are wetlands disappearing?

In a scenario where carbon pollution is left unchecked, along with development of the land wetlands could inhabit, 75% of US coastal wetlands would be lost by 2100. By comparison, conserving all the now undeveloped land that coastal wetlands could migrate into — along with moderate carbon emissions cuts — would reduce losses of coastal wetlands to 17%.

Setting aside land for wetlands to migrate into as seas rise will determine whether or not wetland ecosystems can move to higher ground. Their fates will also depend upon the speed at which industrial pollution raises sea levels and a variety of local factors like combined sewer overflow, maritime traffic, and infrastructure.

How do wetlands benefit economic goals?

In addition to providing breeding grounds for wildlife, wetlands protect humans and their homes and infrastructure from storms. They can capture and store heat-trapping carbon pollution and in some places provide “cultural and social benefits that cannot be monetarily quantified,” said Siddharth Narayan, a researcher at East Carolina University’s coastal studies department. Harriet Tubman led enslaved people to freedom through Mid-Atlantic marshland, for example, and coastal communities in Indonesia and elsewhere use mangroves for dyes for traditional art.

Narayan’s research tends to illuminate the economic benefits of protecting such ecosystems. After Superstorm Sandy, he led research showing Mid-Atlantic marshes protected property worth $625 million. “If those wetlands had been removed, that is by how much the damage would have been increased,” he said.

Where wetlands can grow

As sea levels rise, wetlands can grow on higher ground and expand along shorelines. Here’s how that could play out in hot spots around the country:

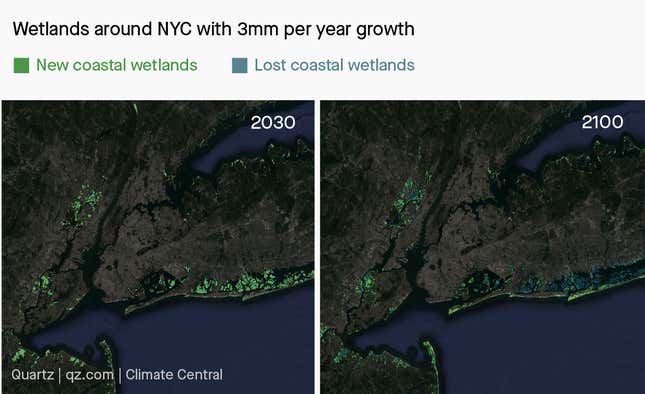

New York Saltmarshes

In a high emissions scenario, the state of New York faces the loss of more than half of its existing wetlands by the end of the century. However, conserving land for wetlands migration could more than offset those losses, increasing the total wetlands area in New York by a fifth.

Preserving wetlands in Jamaica Bay and other parts of New York City will be profoundly challenging as heavy development and a long list of other threats to the ecosystems, including water pollution and displaced mud contribute to rising seas.

“There’s a huge loss of sediment,” said Dorothy Peteet, a researcher at Columbia University and the NASA/Goddard Institute for Space Studies, which has investigated changes in landscapes since the 1700s around Jamaica Bay. “There used to be all these streams that brought in sand and silt and all those are urbanized.”

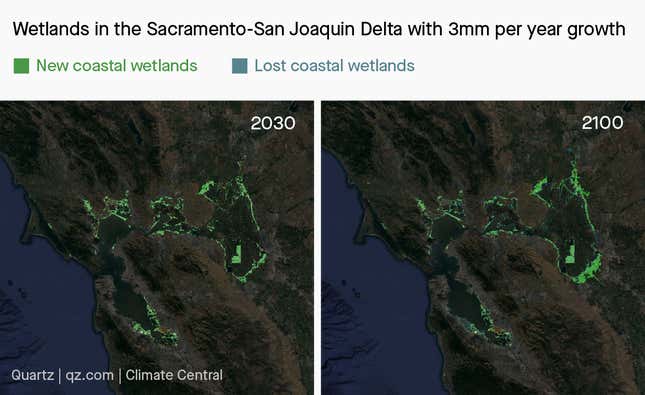

Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

California’s marshes benefit from slower rates of local sea level rise than in other parts of the country, but the Bay Area — where much of California’s coastal marshes are concentrated — faces the challenge of highly developed coasts leaving little room for migration. Under a high emissions scenario, California is projected to lose a third of its existing marshes by 2100, but conserving all currently available land for migration would actually result in more wetlands acreage overall by the end of the century than exists now.

State leaders were relatively quick to recognize the value of restoring Bay Area marshland before accelerating rates of sea level rise make such a task more difficult. In 2016, voters in the nine Bay Area counties approved new property taxes to help fund wetland conservation and development, which is expected to raise $20 million over five years, protecting the region from floods and enhancing its natural environment.

“The campaign was politically astute,” said Letitia Grenier, a scientist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute. “If you look at the campaign materials they were mostly selling clean water and birds — a healthy bay, the concept of living in a healthy place, not so much trying to get into the technical aspects.”

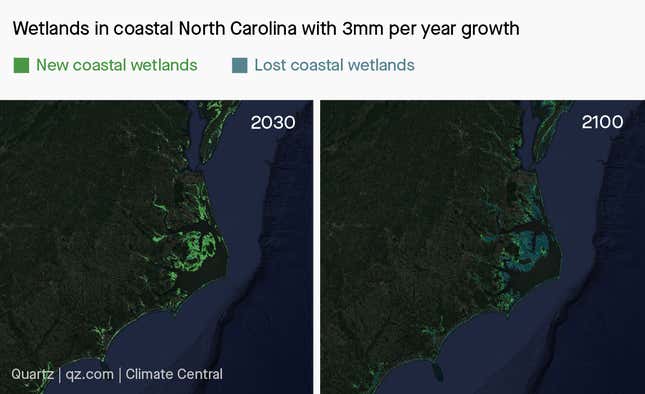

North Carolina Coast

Only a combination of fast wetlands growth and deep and rapid cuts to carbon emissions would prevent the loss of North Carolina’s existing marshes. Under more moderate scenarios, the state could lose almost 90% of its existing coastal wetlands by 2100, though conserving all available land for wetlands to migrate into would offset most of those losses — at the expense of farms and towns, which are already becoming clogged with wetland vegetation.

The state’s high levels of vulnerability to storms and rising seas levels have spurred a hub of research into the use of living shorelines as superior alternatives to seawalls and bulkheads. Living shorelines are small marshes that begin as oyster reefs, and new technology is helping to establish them in rough surf and fine mud.

“We’re beginning to see an emergence of just a wide variety of different technologies,” said Niels Lindquist, a University of North Carolina professor who along with a commercial shellfisher secured patents for a biodegradable composite of plant cloth and cement upon which oysters grow to form a living shoreline. “It’s definitely an exciting time to be in the business.”

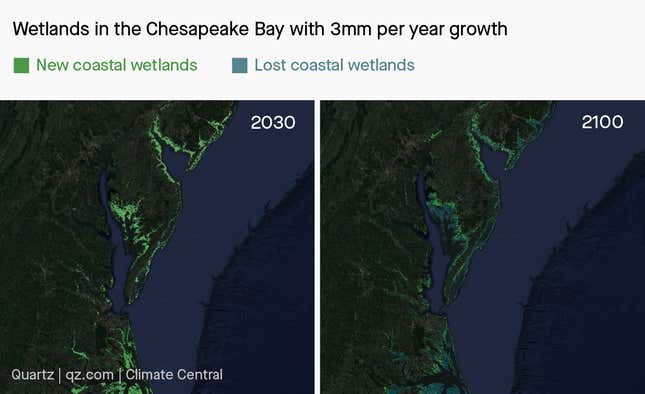

Chesapeake Bay

Tens of thousands of acres of existing saltmarsh are projected to be lost to rising seas in the Chesapeake, though those losses could be entirely offset as wetlands migrate into forested and other rural areas. Dorchester County, home of the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, is expected to lose almost 65,000 acres of current coastal wetlands by 2100 if global carbon emissions remain high.

The changes are already turning counties around Chesapeake Bay into so-called coastal “ghost forests.” These forests of dead trees are the result of rising sea water pushing inland. While stands of dead trees may invoke a sense of ecological calamity, marshland is thriving beneath the barren canopies. The phenomenon is thanks to “relatively low lying elevation and relatively low-slowing” terrain, said Tyler Messerschmidt, a researcher at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science.

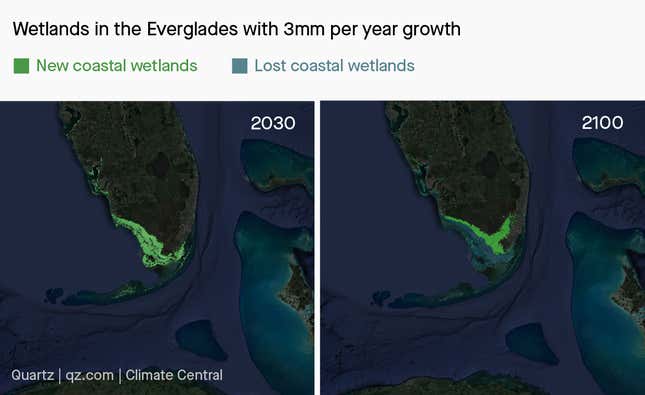

Everglades

Almost half of Florida’s existing coastal wetlands are at risk of being drowned by rising seas by the end of the century, though if wetlands are allowed to migrate into currently undeveloped dryland, the state’s total wetlands area could actually increase overall.

The Everglades National Park is a sprawling protected area that could provide the greatest opportunities in Florida for inland expansion of coastal wetlands, though that would come at a cost to its freshwater wetlands, as saltwater and the plants that rely on it push further into the park.

Those interior wetlands help clean and store water used by millions of Florida residents. Amid sweeping conservation efforts across the park, Audubon Society scientist Shawn Clem said “the importance of our inland wetlands — our freshwater wetlands — are really being overlooked.”

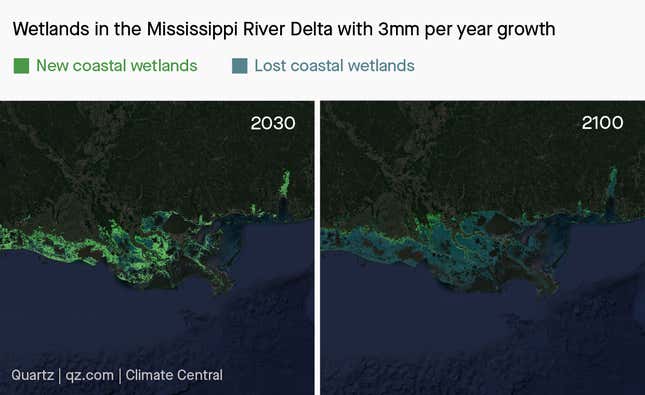

Mississippi River Delta

Home to a third of the coastal wetlands in the contiguous US, Louisiana’s coastal lands are rapidly disappearing because of a long list of factors, including loss of supplies of mud flowing down the Mississippi River, rising sea levels, and damage caused by fossil fuel drillers and invasive rodents.

Even under the rosiest of scenarios, Louisiana could lose three-quarters of its existing coastal wetlands by 2100. “If you sink faster than you can grow, you drown,” said Louisiana State University professor Robert Twilly. “It’s a simple formula.”

If all currently undeveloped dryland is conserved, the migration of wetlands into undeveloped upland areas could offset much but not all of the projected coastal losses. To stem — and in some places reverse — land losses, the state is working with federal and other agencies to move vast amounts of mud through pipes and on barges to where it’s needed the most.