Were Egypt's pyramids built on branch of the Nile River that dried up?

Dozens of Egypt's most famous pyramids may have been built thanks to this long-lost transit corridor

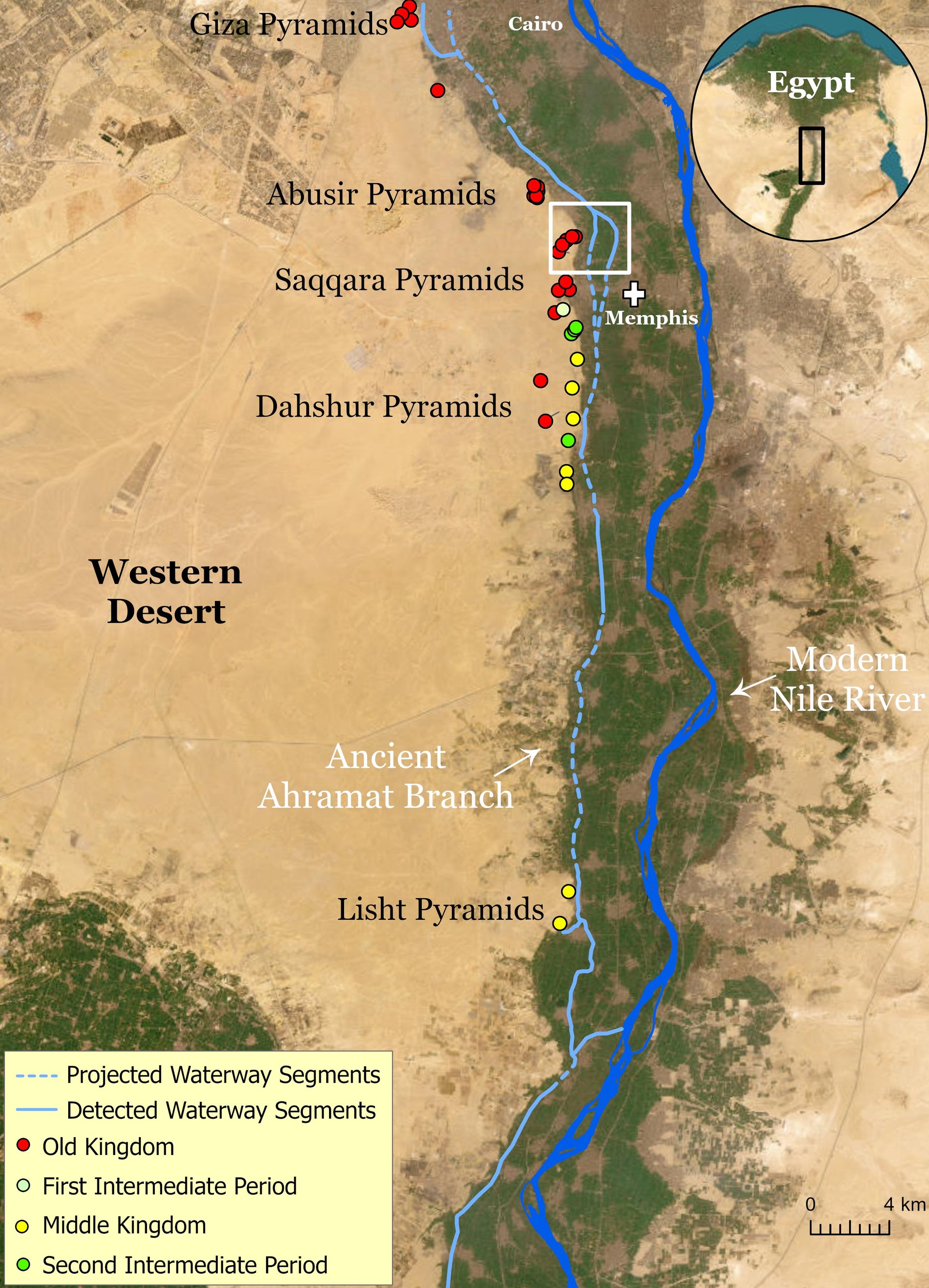

Thirty-one different Egyptian pyramids appear to have been built along a branch of the Nile River that dried up millennia ago, according to new research published in Communications Earth & Environment.

Suggested Reading

The group of pyramids — which include the famous pyramids of Giza and others like the Bent Pyramid and the Step Pyramid of Djoser — now exist on a narrow strip of desert west of the Nile. They were build over a millennium, beginning about 4,700 years ago. According to the authors of the recent study, there was once a 40-mile-long (64-kilometer) branch of the Nile that extended through the now inhospitable landscape, explaining the rather odd placement of the pyramids so far from the Nile, the longest river in the world and the lifeblood of Ancient Egyptian civilization.

Related Content

“Revealing this extinct Nile branch can provide a more refined idea of where ancient settlements were possibly located in relation to it and prevent them from being lost to rapid urbanization,” the team wrote. “This could improve the protection measures of Egyptian cultural heritage.”

The team identified the branch — long since filled in by silt — using satellite imagery, geophysical surveys, and sediment cores sampled from the Western Desert Plateau. They propose dubbing the ancient branch Ahramat, Arabic for “pyramids.”

The team also found that many of the pyramids they studied along the Western Desert Plateau had causeways which terminated where the Ahramat Branch ran. Thus, the team proposes that the river branch was likely used to transport construction materials for the pyramids, a set of projects so gargantuan that the History Channel “Aliens” meme always needs to be kept close at hand.

Inlets that fed the Ahramat Branch are also filled in by sand today, making them invisible to optical satellite imagery. But radar and topographic data of the sites revealed the inlets’ riverbeds as well as the causeways that led to the pyramids of Pepi II and Merenre.

The causeways of several other pyramids (Khafre, Menakure, and Kentkaus) led to another arm of the river the team dubbed the Giza Inlet, indicating that the river branch was still running in the Old Kingdom’s fourth dynasty. Archaeologist Eman Ghoneim from the University of North Carolina Wilmington led the research.

However, the team concluded that the writing was on the wall for the Ahramat Branch beginning around 4,200 years ago, when a major drought may have increased the amount of wind-blown sand that slowly filled in the branch, eventually obscuring it even to satellite imagery. But thanks to radar imagery and sediment coring, an ancient resource of the Egyptians has come to light.