Electrification and Brexit are killing the British car industry

The UK is struggling to build a battery industry—and its new isolation isn't helping.

When US carmaker Ford on Feb. 14 announced 1,300 job cuts in the UK, it was just the latest blow for an industry that’s been struggling to keep up production levels in a post-Brexit, pandemic-hit economy that’s on the brink of recession.

Suggested Reading

Globally, the auto industry is beginning a wholesale change to the way it operates, creating battery-building capacity and the expertise necessary to make electric cars instead of petrol vehicles. But the UK’s recent record on getting cars off the production line, plus some high-profile failures, suggest it might struggle more than most countries.

Related Content

The UK’s car-making heyday is in the distant past. Production peaked in 1972 with close to two million cars made that year, according to the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), and the country’s output has fluctuated ever since. A steady rise over the early 2010s was summarily reversed in 2016, the same year the UK voted to leave the EU: The UK made well over 1.5 million cars in 2016, but that number had halved to just 775,000 by 2022.

Why is electrification hard for the UK?

One area where the UK has long excelled is R&D, with some of the world’s best research institutions and a long history of high-level engineering. Building batteries at scale shouldn’t be an insurmountable challenge. And, if it proved too expensive, importing them could be an option.

Yet the UK’s attempts to build a battery industry are faltering. In January 2023, the lithium-ion battery startup Britishvolt, which was building a massive gigafactory in Northumberland, collapsed into bankruptcy, leaving £120 million ($146 million) in debt.

“Britishvolt collapsed because, much the same as any new technology, converting a promising idea for EV batteries into profits requires extremely hefty costs to be paid up-front,” Rebecca Parry, a professor at Nottingham Law School, told Energy Live News. The company faced high competition from abroad and, allegedly, runaway internal costs. “It was effectively a startup and in spite of investment, it had not by the end of 2022 developed a working prototype and it was still building its factory,” Parry said.

Why not import batteries?

Japanese carmaker Nissan in 2022 became the biggest carmaker in the UK, producing 16.5% of all UK vehicles, a change that came about in part because other big makers pulled out entirely. Honda closed its Swindon operations in July 2021, resulting in the loss of over 3,000 jobs. Vauxhall stopped producing Astra cars at its Wirral factory in April 2022, though its owner, Stellantis, does plan to invest £100 million “supported by the UK government to secure an all-electric future for the plant,” according to a 2021 announcement.

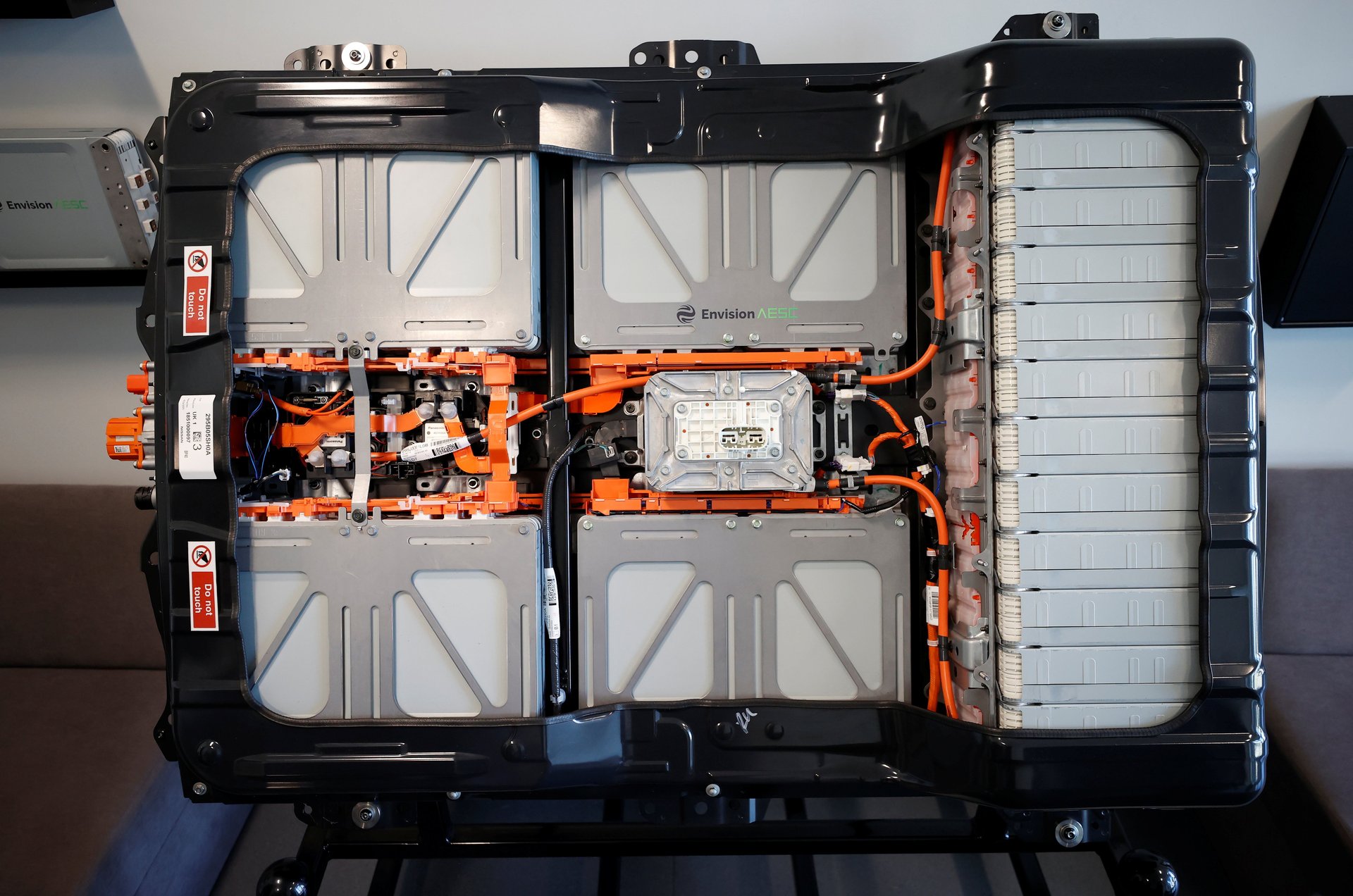

Nissan is still backing a huge gigafactory project in Sunderland, where batteries will be made close to its production plant, a sign that the company thinks making EV batteries—which are large, complex, and, of course, vital to the running of an electric vehicle—close to where the cars are assembled is important.

The UK has long imported technical products, including car components. But while Brexit didn’t stop imports or exports, it made some of them them a lot more complicated, expensive, and uncertain. Years of negotiation towards a “divorce” deal between the UK and the EU has left grey areas that are still being worked out. The Economist pointed out that the crankshaft in a Mini made by BMW has to cross the English Channel three times for various stages of its manufacture before it can be installed in a car in the UK. Manufacturing processes like this are becoming much more onerous post-Brexit.

Ford also announced layoffs today in Germany, citing a wide-ranging restructure of its business. As an American company, it’s likely being tempted by huge US government incentives to invest in a US-based EV production industry. Those incentives are even luring away British companies—yet another blow to the country’s struggling auto industry.