Hello Quartz readers,

We’re hitting your inbox thrice this week. Today (#2), we’ll be looking at the politics of naming a virus. Tomorrow, we’ll go down a rabbit hole on the subject of bailouts. Because we’re all wondering the same thing: So, um, how much money will we need in order to dig out of this?

Your queries, thoughts, feedback, and idle musings are greatly appreciated. Keep them coming at needtoknow@qz.com. Let’s get started.

That which we call a rona

It started as the “Wuhan virus,” then the “Wuhan coronavirus” or “China coronavirus,” and subsequently 2019-nCoV. Finally, on Feb. 11, the WHO gave the disease an official name—Covid-19, where Covid stands for COronaVIrus Disease.

But the virus that causes the disease, named by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, is SARS-CoV-2—a reference to the new coronavirus’s genetic link to the virus that caused the 2003 SARS outbreak. All of which is to say: One tests positive for SARS-CoV-2, not Covid-19, as it’s the virus and not the disease that does the infecting.

And yet, the WHO almost never refers to it as SARS-CoV-2. Instead, it uses “Covid-19 virus” or “the virus responsible for Covid-19.” Technically, the first one is redundant: Spelled out, it would essentially read “coronavirus disease virus.”

The broader contention over how to label the new coronavirus underscores how, in the combustible mix of a public health crisis and geopolitical rivalries, names do far more than convey information—they draw battle lines. US president Donald Trump insists on using terms like “the Chinese Virus.” A White House official called it “kung-flu” in front of a Chinese-American journalist. In this context, what the WHO—as a neutral, international agency—calls the virus suddenly carries a lot of weight.

The WHO writes on its website that it steers clear of SARS-CoV-2 because “using the name SARS can have unintended consequences in terms of creating unnecessary fear for some populations, especially in Asia which was worst affected by the SARS outbreak in 2003.” In a statement to Quartz, the agency added that under an agreement with the World Organization for Animal Health and the Food and Agriculture Organisation, it “had to find a name that did not refer to a geographical location, an animal, an individual, or group of people, and which is also pronounceable and related to the disease.” However, on the WHO’s list of pandemic and epidemic diseases, there are several other diseases that explicitly refer to a geographic location: Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS); Lassa fever, referring to a town in Nigeria; and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever.

Some have argued that SARS-CoV-2 can cause confusion. In a letter published last month in the Lancet, six co-authors from China (including three from the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention) argued that naming the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 is “truly misleading” because it “implies that it causes SARS or similar,” especially for those without technical expertise in virology. The authors added that the name SARS-CoV-2 “might have adverse effects on the social stability and economic development” of countries experiencing the epidemic, as “people develop panic at the thought of a re-occurrence of SARS.” Instead, they proposed naming the virus human coronavirus 2019, or HCoV-19.

Responding to the letter, a group of 12 scientists based in the US, Hong Kong, and mainland China argued that SARS-CoV-2 is in fact an appropriate name for the new coronavirus. The name, they argued, “does not derive from the name of the SARS disease,” but refers to its links with the viruses in the SARS viral species. “In other words, viruses in this species can be named SARS regardless of whether or not they cause SARS-like diseases,” they wrote. The authors also argue that far from damaging social stability, “keeping SARS in the names of viruses of that species would… keep the general public vigilant and prepared to respond quickly in the event of a new viral emergence.”

Gravity

The effect of coronavirus on the global economy isn’t just visible from the trading floor—it’s also visible from space. Remote-sensing data gathered by satellites in orbit and augmented by remote sensors on the ground provide grist for the machine-learning mills operated by companies like Orbital Insight, whose analysts are turning up evidence of how the Covid-19 epidemic is upending the flow of goods and people around the world.

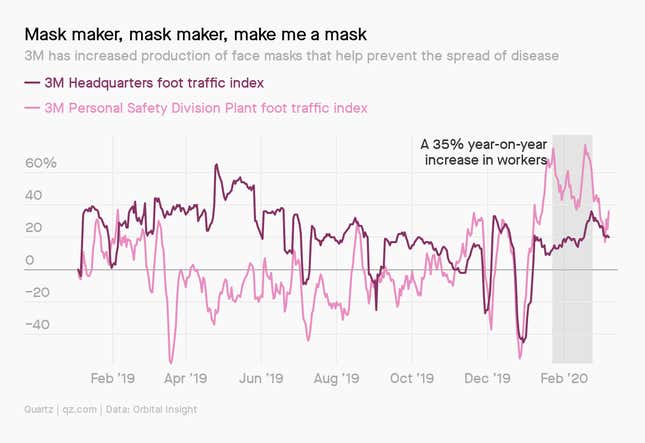

Consider 3M, the US conglomerate that makes, among other things, the kind of masks used to prevent the spread of airborne disease. Demand for these masks is soaring, and the company has said it is ramping up production. Sure enough, sensors tracking daily employee foot traffic at 3M facilities confirm it.

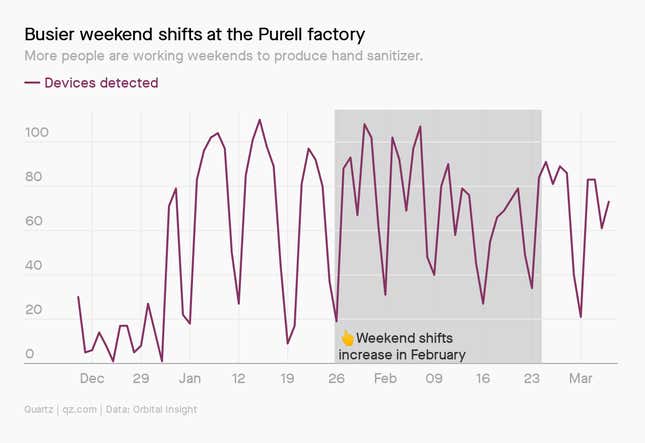

What else do you need to fight the spread of a virus? Hand sanitizer. Orbital Insight’s platform can analyze anonymized data that shows how many mobile devices are in a given geographic area, which gives them a proxy to measure the number of people at places like the Purell factory. Gojo, the firm behind Purell, has said it’s putting more people to work, and data suggests the company started increasing weekend shifts in February.

Death becomes heard

You know the story. A character starts coughing—at first quietly and then, over the course of the movie, louder and more aggressively until, before you know it, they’re dead. The “Incurable Cough of Death,” as the site TV Tropes dubs it, is proving to be a major source of anxiety during the coronavirus pandemic.

This conceit goes back hundreds of years in popular culture; while its origins are hard to pinpoint, it is prominent in Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre, Les Misérables and La bohème. The incurable cough is basically a version of “Chekhov’s Gun,” the principle that states all elements of a story—however seemingly small—will eventually matter. Here are just some of the movies and TV shows that feature this timeless trope.

- Chernobyl

- Friends

- Lost

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer

- Moulin Rouge!

- Braveheart

- Contagion

- Man on the Moon

- Captain America: The Winter Soldier

- The End of the Affair

- Brian’s Song

- Inception

- Return of the Jedi

- The Road

- Gremlins 2: The New Batch

Preserving the taste

If there exists any silver lining to being shut away and unwell—whether due to a common ailment or Covid-19—one can certainly be found in a home kitchen. And as more employees are asked to work remotely, it’s a room where they might be spending a lot more time.

Quartz reporter Chase Purdy, who covers the future of food, is giving a lot of thought to cooking as an act of self-care (that’s his challah 👇). Quartz members can read more about his journey here, or sign up for a 7-day free trial to sneak a peek.

We’ve also got the beginning of a Quarantine Cookbook going, to help make the most of long-shelf-life staples. If you have a recipe you want to share, send it on over to needtoknow@qz.com.

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 236,420 confirmed cases; 84,962 classified as “recovered.”

- Coolcoolcool: 90% of India’s workforce has no option of calling in sick.

- Hire calling: Domino’s and Amazon need thousands of new workers.

- Ma hero: Jack Ma is the coronavirus ambassador that China needs.

- News you can use: All the streaming services with coronavirus discounts and free trials.

+ for Quartz members:

Really, sign up for a free trial!

- A tale of two countries: Which health system is best?

- Pillow talk: Working from bed can prevent back pain.

- Huh: Music streaming may actually be falling.

- Delivering: Amazon was made for this moment.

- Quarantine life: Look out for a baby and divorce booms.

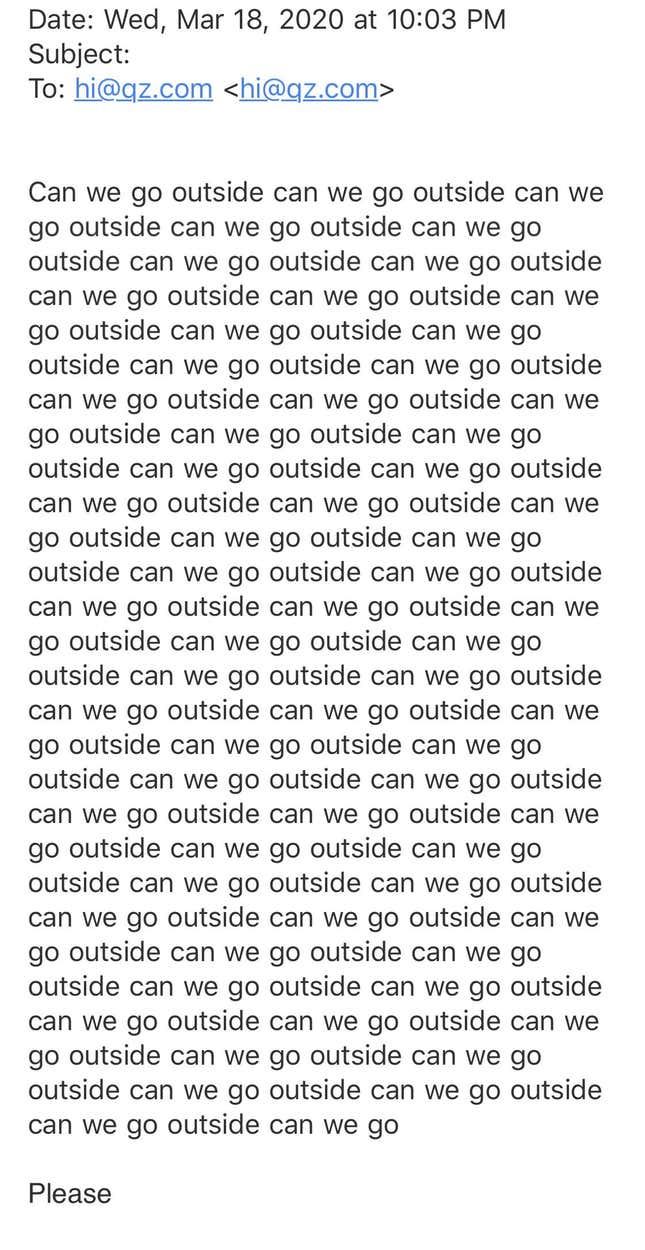

PS: This week’s award for most relatable reader email goes to the frustrated soul who sent us this.

We see you, reader, and we understand. (Also the answer is: Yes! It’s okay to take a walk, as long as you’re maintaining a distance of around six feet from other people.)

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at needtoknow@qz.com, and live your best Quartz life by downloading our app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Mary Hui, Tim Fernholz, Adam Epstein, Chase Purdy, and Kira Bindrim.