Hello Quartz readers,

Over the past few weeks, we’ve gotten a lot of questions about immunity.

- Michele asked, “If you test and have antibodies for Covid-19, does that mean you’ve had it? Do the antibodies prevent you from getting it again?”

- Cornelia asked, “Do scientists have any idea how much exposure we need to develop immunity? Is there a certain level of antibody in blood test results that will be necessary?”

- And Kamala plotted out the next Christopher Nolan movie, asking “Could there be an intentional suppression of information because if getting Covid grants immunity, and most cases aren’t serious, and even 20% of cases are asymptomatic, might many people want to get it? Because then they could be free of restrictions? And we would end up with two levels of humans in society: those with immunity and those without??”

Unfortunately, we don’t have all the answers yet. Today we want to talk about what we do know, and why a complete grasp of immunity is so hard to come by.

✉️ Keep sending those questions. Now, let’s get started.

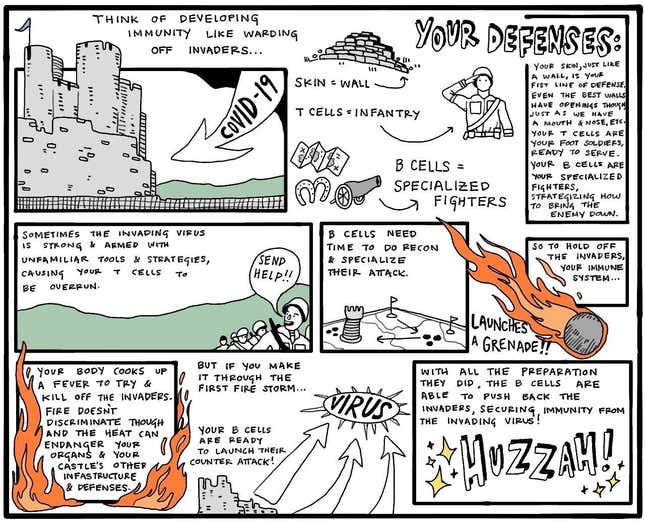

My body is a castle

Scientists only became aware of SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes Covid-19, late last year. Most of our immune systems, meanwhile, have still never heard of it. For now, we have to rely on our bodies—rather than a vaccine or targeted medication—to fight off the virus.

The good news is: Evolution designed the immune system to do just that. The bad news: Its response isn’t always predictable. The immune system is complex in its own right, and varies tremendously from person to person. This makes it hard to know how and when to intervene when it’s overwhelmed. In order to slow the spread of Covid-19, it will be crucial to understand exactly how the immune system tackles the disease.

Scientists have the basics of the immune system down pat. With any new viral infection, the body first deploys T cells, which find and kill infected cells. T cells are in limited supply; if there’s still an infection after they’re depleted, the body will unleash a fever to make the environment uninhabitable for the virus. After about a week, the adaptive immune system kicks in, using B cells to make antibodies that can flag sick cells for annihilation even faster. Those antibodies stick around after an infection is over, in case of a future invasion.

If you’re thinking “Man it’d be helpful to see that as a comic strip,” don’t worry. We’ve got you.

But for all we know about the immune response to SARS-CoV-2, there’s still a lot we don’t:

- We don’t know how well T cells can do their jobs (age tends to make them sloppier).

- We don’t know when T cells will deplete during an infection. This inflection point is likely behind the brief recovery, followed by a second wave of symptoms, reported by many Covid-19 patients.

- We don’t know when exactly B cells will get SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies ready to go.

- We don’t know why some people get severe fevers and inflammatory responses (i.e. a body grenade that your organs can’t handle).

- We don’t know how long those antibodies will stick around in a meaningful way to fight future infections. Research on similar coronaviruses suggests antibodies to them may last a year or more—but that their power to neutralize the virus degrades over time.

In other words: It’s not yet clear how long immunity will last, or whether it will be the same for everyone.

Data from China on SARS-CoV-2 has shown a wide range of antibody responses. In a group of 175 patients, 70% produced a high concentration (known as a titer) of antibodies. The rest managed to fight off the infection with a minimal titer, suggesting they beat the virus with their T cell response or other parts of the immune system. Which is fine—but those people may not have long-lasting immunity.

Knowing all these details will be critical for designing tools—tests, treatments, and vaccines—to help us manage the spread and impact of Covid-19. But unearthing the answers will take time: to carry out antibody surveys on large numbers of people, repeatedly, watching for re-infection; and to gauge the safety of candidate vaccines first in animals (when we can), and then in people. Until then, immunity is an open question.

Statistically speaking

You’re probably hearing a lot about serology tests, which detect antibodies produced by an infection. Designing a serology test involves a balance between sensitivity—the ability to detect any antibodies whatsoever—and specificity, the ability to exclude all antibodies except those targeting this virus.

Even if we perfectly understood the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and immunity, serology test results might still be misleading when only a small portion of the population has been infected—thanks to a fluke of epidemiological statistics. Zachary Binney, an epidemiologist at Emory University, explained it this way:

Imagine a group of 100 people, 10 of whom are infected. You have a test that, similar to most of the serology tests being marketed today, is 90% effective in correctly identifying both positive and negative cases. That means you’ll get: 9 correct positives and 81 correct negatives, plus 9 false positives and 1 false negative. Of your 18 total positives, only 9 actually have the virus (and you’ve given the all-clear to one person who is actually infected). So a positive result is only accurate half the time. But try the math again when 40 people are infected, and the accuracy jumps to 89%.

TLDR: Frustratingly, more people need to catch the virus before we can have a better sense of how widespread immunity really is.

Immunoprivileged

Complications notwithstanding, the notion of antibody screening—using data from serology tests to determine who is eligible to participate in society—is gaining traction. But history offers lessons here. In the New York Times, historian Kathryn Olivarius looks at yellow fever in 19th century New Orleans. The disease killed about half the people it infected, leaving survivors permanently “acclimated.”

Yellow fever did not make the South into a slave society, but it widened the divide between rich and poor. High mortality, it turns out, was economically profitable for New Orleans’s most powerful citizens because yellow fever kept wage workers insecure, and so unable to bargain effectively. It’s no surprise, then, that city politicians proved unwilling to spend tax money on sanitation and quarantine efforts, and instead argued that the best solution to yellow fever was, paradoxically, more yellow fever. The burden was on the working classes to get acclimated, not on the rich and powerful to invest in safety net infrastructure.

I feel so vaccine

There are currently over 100 Covid-19 vaccines in development, which use a variety of tactics to prompt the immune system into creating antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 pathogens. Vaccines show the immune system a biological mugshot of the pathogen, some using proteins and peptides, others bits of genetic material encapsulated in other viruses, and others weakened or immobile bits of the pathogenic virus itself.

Most of these targets are inspired by vaccines that have worked safely in the past—or at least been heavily researched. Scientists are drawing inspiration from techniques that were employed when fighting SARS, MERS, and even Ebola. In theory, these strategies should prompt B cells to make antibodies and keep them in the body long enough to prevent infections from sickening us.

The resulting race likely won’t have a single winner, but rather a handful. “It’s possible that out of the 50 or 80 candidates, there could be three or four that could be effective,” says Mark Poznansky, an immunologist and director of the vaccine and immunotherapy center at Mass General Hospital. “Fundamentally viruses have been infecting humans for millions of years, so it’s unlikely this represents a new type of battle. But because there’s a lack of immunity in most of the population of humans, it’s like a vast, horrendous experiment on our immune systems.”

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 3,083,467 confirmed cases; 915,988 classified as “recovered.

- A woman’s touch: Scientists are testing whether estrogen could help men survive Covid-19.

- Plant life: How a Volkswagen plant is going back to work.

- Can we meat: Tyson says the US food supply chain is breaking.

- In this together: All the Covid-19 commercial cliches in one supercut.

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at needtoknow@qz.com, and live your best Quartz life by downloading our app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Katherine Foley, Tim McDonnell, Hailey Morey, and Kira Bindrim.