Coronavirus: No time to die

Hello Quartz readers,

Hello Quartz readers,

It looks like some of you took our last subject line seriously. And sure, when you see an email labeled “This is only a test” in your inbox, we can see how that might be confusing. But you missed a doozy: We had a primer on inflation, two charts, a pop quiz, a puppy, and one perfect Zoolander gif. Be sure to check it out.

And just in case, here are some other subject lines to watch out for:

- Coronavirus: Let’s keep our social distance

- Coronavirus: WHO are you again?

- Coronavirus: Don’t reopen this email

- Coronavirus: It’s your LAST CHANCE!

- Coronavirus: Please add me to your LinkedIn network

Okay, let’s get started.

The wonder years

Every number tells a story. So far, the story of coronavirus has largely been told in death counts. Assembled by epidemiologists and public health leaders, those figures paint a picture of devastating loss: Out of more than 9 million cases worldwide, just over 500,000 people have died.

But some public health wonks use another number that tells a slightly different story: years of life lost, or YLLs (✦ Quartz member exclusive). Based on early averages, Covid-19 cuts 12 to 14 years off the lifespan of its victims.

YLLs, which have been used in academic circles since the 1940s, put extra weight on people who die at a younger age. If you’d expect that people in a population of 1,000 would live to 85, but 100 of them died at 75 because of an illness, the total fatalities would be 100, but the YLLs would be 1,000 (100 lives multiplied by 10 years fewer each). If that same group of people died at 65, fatalities would remain at 100—but YLLs would be 2,000. Suddenly, the problem seems more grave.

Economists in particular appreciate the YLL because it can expose the financial toll of a disease, in addition to the incalculable loss of human life. The earlier a disease kills, the more earning power it eliminates.

This approach may be useful for public health officials trying to choose a course of action with a limited budget. If a large group of children were dying of diarrheal diseases in one country, the YLLs would be higher than the same number of older adults dying of heart attacks. You could save more years of life—and potentially dollars—by implementing better sanitation systems than by investing more in defibrillators, even though the fatalities would be the same.

But using YLL to inform those kinds of decisions is far from simple. For one, life expectancy is a moving target. When researchers published the first Global Burden of Disease report in 1993, they used Japanese women, with an average life expectancy of 82.5 years, as their baseline; for men, they assumed 80 years. More recently, the WHO has switched to nearly 92 years for all genders, based on the predicted life expectancy for women living in South Korea in 2050. Of course, not everyone will reach their 10th decade, so a more precise YLL would be calibrated by country, or with even more nuance.

There are ethical implications, too. Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, some countries were slow to implement measures to mitigate the virus’s spread, arguing that because the coronavirus was most fatal in the elderly, it wasn’t a serious threat. Perhaps unwittingly, that’s an argument based on YLLs. And as the WHO’s director-general pointed out at the time, it’s also age discrimination.

✦ How do you measure a year? In daylights, in sunsets, in midnights, in cups of coffee. Also in Quartz memberships—you only need one. Members enjoy unlimited access to our stories, presentations, field guides, and workshops. And as part of our summer sale, the first year is yours for 50% off. ✦

Going up?

An elevator is the perfect incubator for an airborne virus. So how can we safely shuttle people in these crowded, sealed-off boxes? Architects at The Manser Practice in London suggest modernizing a Victorian-era single-occupancy model called the paternoster lift.

Custom designed by architect Peter Ellis in 1868 for Liverpool’s Oriel Chambers office building (a polarizing modernist landmark), the paternoster features a series of small, open compartments moving continuously in a loop. Passengers never have to fuss with buttons; they simply hop on when they see an open compartment and disembark when they reach their floor. Yes, it’s dangerous!

“In the 1900s, the paternoster demonstrated visual modernity,” Jeannot Simmen writes in Elevation: A cultural history of the elevator. “All other vehicles required coachmen, guides, conductors, or elevator attendants. Only the all-round elevator showed a transport system in a simple arrangement without a guard and without doors.”

Too many cooks

Restaurant meals are looking different these days, as small eateries, major chains, and hospitality groups alike figure out the right recipe for socially distanced dining. Here are a few examples from around the world:

☀️ In New York City, 6,000 restaurants have signed up to be a part of the Open Restaurants program, which will allow for expanded outdoor dining in closed-down city streets.

🍲 Karma Hospitality, a boutique hotel chain in India, changed its menu to remove any dish that requires more than one chef.

🧼 Several corporations, including TGI Fridays and the Cheesecake Factory, have designated scrubbers: employees who do nothing but roam the restaurant, disinfecting full time.

🍺 In Dublin, pubs must serve food (not just alcohol), and customers have to leave after an hour and 45 minutes.

Have you braved the restaurant scene? We want to hear about it.

Well, shoe-t

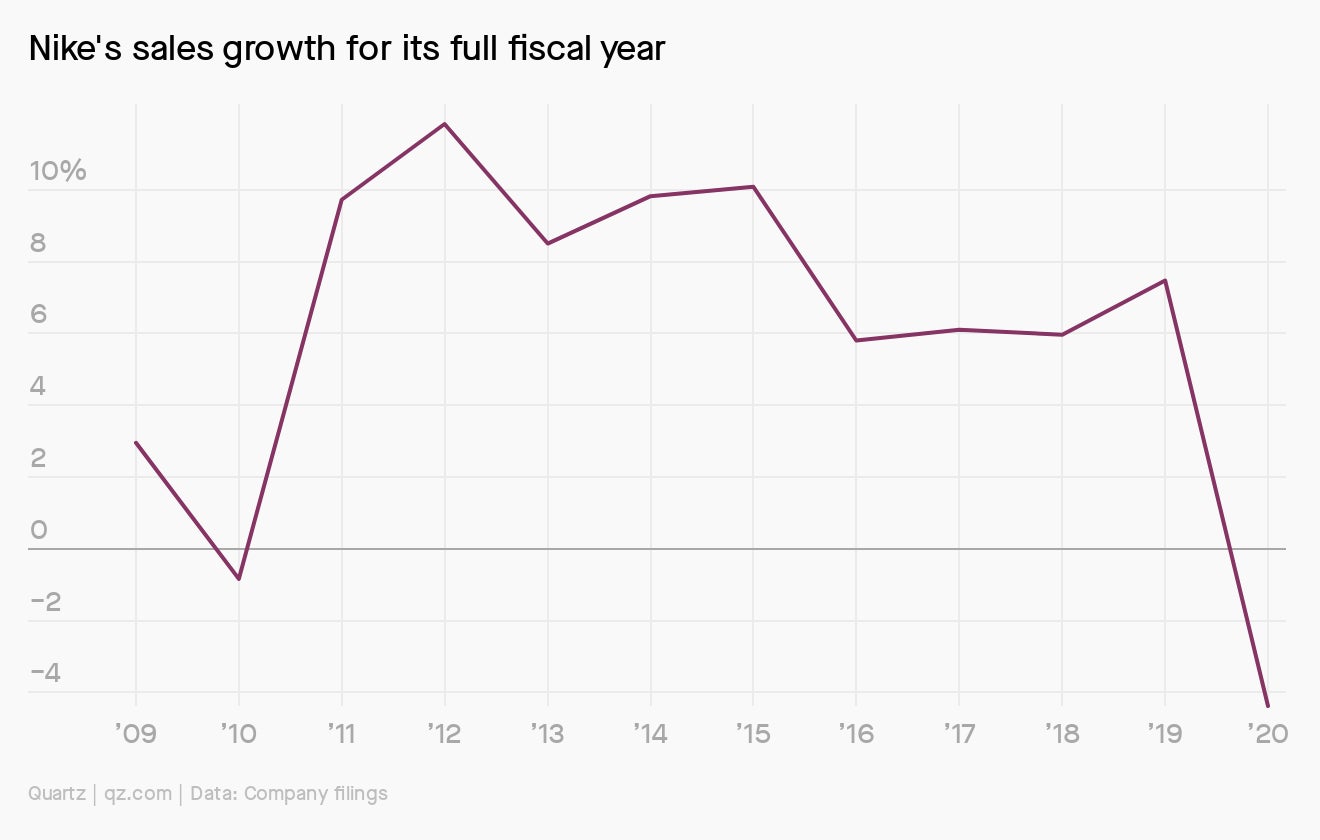

When Nike kicked off its 2020 fiscal year last June, this is not the outcome it was expecting.

Through the first half of the fiscal year that ended May 31, business had been humming: Sales were up 9%. But when the pandemic hit in the second half, the impact was too great for even Nike to withstand. For the full year, Nike’s sales fell 4% versus the same period last year “due to the impact of Covid-19 on business operations, primarily in the fourth quarter.”

For two months of that quarter, 90% of Nike’s physical stores were closed in North America, Europe, much of Asia (excluding China), and other regions. Many of Nike’s retail partners had to close stores as well. The company still did 65% of its annual sales through those wholesale accounts, and its own digital sales jumped 79%. But that still only brought them to 30% of Nike’s total business.

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 10,424,992 confirmed cases; 5,262,705 classified as “recovered.”

- Long layover: Taiwan’s one-week quarantine could be the new normal of business travel.

- Demand and supply: Dexamethasone’s supply chain is the most exciting thing about it.

- Passing the test: The US now has more Covid-19 tests than it knows what to do with.

- Lesson plan: What parents can learn from childcare centers that stayed open.

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at [email protected], and live your best Quartz life by downloading our app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Katherine Foley, Anne Quito, Niharika Sharma, Marc Bain, and Kira Bindrim.