This week’s lead story is written by Lila MacLellan, a senior reporter at Quartz. Here, she looks at a surprising feature of executive business programs from the 1950s—classes for wives—and considers their legacy on business schools today.

Picture a US business school in the 1950s.

You might imagine imposing brick buildings with men, mostly white, mostly affluent, flowing through the hallways. You might also imagine that, with the rare exception, the only women in the b-school hallways are assistants and secretaries—not students. But there you’d be wrong.

Women did attend business schools well before these institutions became official co-ed spaces, just not in the way you might expect.

Four years ago, Allison Louise Elias, a gender historian and assistant professor at University of Virginia Darden School of Business learned that women were welcomed into business schools as the wives of businessmen enrolled in then-new executive business programs—short, intensive courses for men aspiring to leadership positions. Think of it like a “finishing school” for executive wives, says Elias.

At Harvard, for example, in the last week of the executive education program, the students’ wives would be invited to Cambridge to join their husbands who had been away from home for 12 weeks, living in dormitories. The wives could “see what their husbands had been up to,” says Elias, and could become acquainted with business culture. Other programs invited wives to campus for a weekend or a day, here or there.

While their husbands might be learning how to navigate the upper echelons of management, the wives might study the Cha-Cha-Cha or visit a local museum to take in some high culture. It was thought that this coaching would prep the wives to support their husbands as they climbed the corporate ranks, says Elias, who co-authored a new paper about executive wives with Rolv Petter Amdam, a Norwegian business historian.

The forgotten history of executive wives’ “education” is another clue in explaining why, even today, business schools, and proverbial corner offices remain male-dominated spaces, Elias says. Back then, business schools were deeply committed to the “separate spheres” ideology, which dictated that men belonged in the workplace and women at home—or perhaps, for women of a certain social status, at a charity luncheon writing checks.

The idea has stuck around, in less conspicuous ways, in part due to imprint theory, a concept in organizational studies, which suggests that the norms established during an institution’s formative years—in this case the early years of business schools—are particularly durable, Elias explains. That’s why today’s MBA programs can’t afford to ignore this piece of history.

Executive business programs were first offered on college campuses in the post-war period, starting at Harvard Business School in 1945. Around that time, companies began to conduct “wife screenings” when choosing who to hire and promote, a practice that persisted until the 1970s, despite 60s-era civil rights laws that prohibited employers from considering familial status in the hiring process.

Wives could make or break their husband’s career, Elias explains. When a man was up for a promotion, his boss would be sure to vet his spouse, too, whether at an interview in the corporate office or informally at a dinner party.

In a strange sense, these customs—the “finishing school” classes and the screenings—also acknowledged the sheer amount of unpaid labor that went into being a businessman’s wife. The companies understood the effect a wife could have on a business’s bottom line. They did not try to pretend that the globe-trotting executive could also manage family life and raise children while resettling periodically in a new city.

Essentially what you had was akin to a business partnership. “The wife was very integral to her husband’s career success,” says Elias. “Even though she had a distinctive role, she was definitely bolstering him.”

Keep reading this story on Quartz.

Five things we learned this week

📈 May was the worst month for startup layoffs since the start of the pandemic. Last month’s layoff total was up 350% from April, with Getir, Peloton, and Klarna leading the pack.

🇮🇹 Italy is a global leader when it comes to responsible, sustainable business. A raft of companies across the country, some public, but most private, in tech, fashion, food, pharmaceuticals and other industries, are putting purpose first.

💳 American Express just made its first investment in an African startup. With its investment in Klasha, a fintech company, Amex joins Visa and Mastercard which have been in Africa’s fintech scene since 2018.

🍰 What do people in India leave in their Ubers? Birthday cakes and stickers. Water bottles (mostly on Sundays) and clothes (mostly on Saturdays). And so much more!

🤝 Inside Elon Musk’s new legal strategy for ditching his Twitter deal. Ann Lipton, a corporate and securities law expert, explains.

Quartz Obsession Interlude

We’re all pod people now. There are more than 800,000 active podcasts, and making a new one is (almost) as simple as finding a quiet space to record. But that’s where the simplicity ends. As podcasting becomes big business, the industry has decisions to make about how much data to collect from listeners, how important is the role of the host, and who will have the resources to survive. 🎧 Learn more in this week’s episode of the Quartz Obsession podcast.

Listen on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

TGI…Thursday?

The world’s biggest four-day workweek trial is kicking off in the UK, with more than 70 companies and 3,300 people aboard for the ride.

For the next six months, employees of participating companies will work 80% of their usual hours while earning the same pay. Workers will be expected to maintain the same level of productivity, per the trial’s “100:80:100” model. (Employees make 100% of their pay, working 80% of their prior schedule, maintaining 100% of their prior output.)

The massive experiment was co-organized by 4 Day Week UK Campaign and 4 Day Week Global, a nonprofit group led by Andrew Barnes, the founder of a New Zealand insurance company who first cut his own firm’s workweek in 2018, inspired by some airplane reading. The shorter week left his employees feeling more motivated and productive, and Barnes has been advocating for more organizations to make the switch ever since.

The idea has been taking hold, with companies like the US-based crowdfunding site Kickstarter heeding the group’s call. Around the US, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, the number of firms and governments that have found their way to a four-day week keeps growing.

Among employees, the concept is extraordinarily popular: One recent US survey found that 92% of working adults said they would prefer to work four 10-hour days per week (instead of five eight-hour days), another common way to design a four-day schedule.

Data from the UK’s six-month trial should help answer some critical questions about this rising benefit. Like, does it really keep employees happier and healthier without hindering a company’s operations? Or is it a pipe dream that might even worsen the climate crisis? Will workers be less likely to burn out or quit? Will they get more shuteye? Overall will shorter weeks help companies use less energy?

The trial is being co-produced by Autonomy, the UK think tank that also analyzed the results of Iceland’s highly successful, multi-year four-day week trial. Academics from Cambridge University, Oxford University, and Boston College will be tracking the trial’s effects, too.

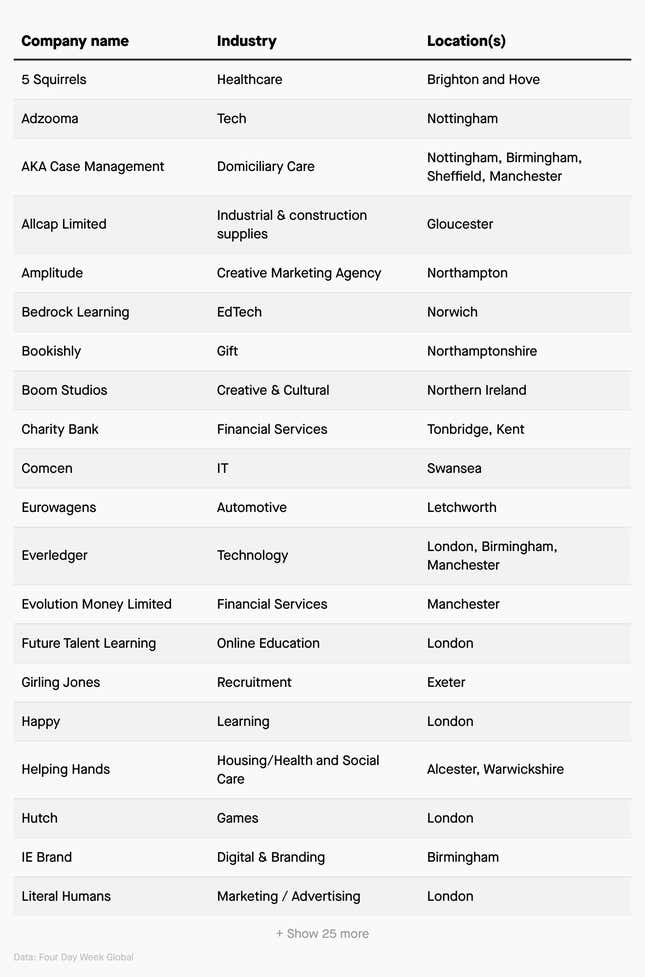

The table below shows 20 companies which have committed to the experiment. See the full list of 45 companies that have agreed to go public about their participation in the trial by clicking through to Quartz.

The companies represent a range of industries, suggesting that the four-day week doesn’t need to be reserved for tech and other office-based employees who already enjoy plum perks, like the ability to work from home. Similar large experiments in Spain and Scotland are set to begin later this year.

You got The Memo!

Today’s Memo was written by Lila MacLellan, and edited by Francesca Donner. The Quartz at Work team can be reached at [email protected].

Did someone forward you this email? Sign up for future installments here. Get the most out of Quartz by downloading our app and becoming a member.