Hi Quartz members,

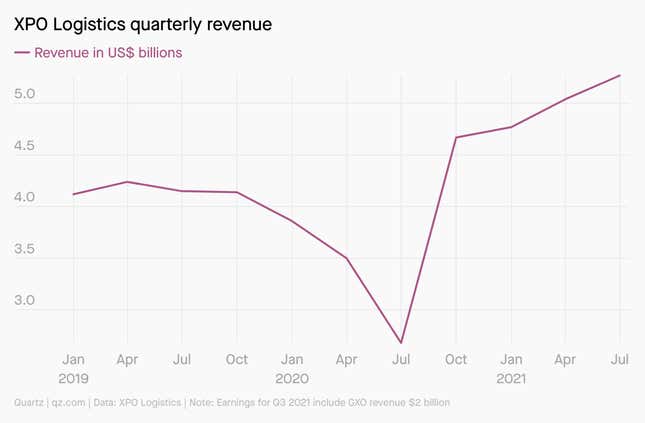

XPO Logistics’ quarterly earnings statements are starting to sound like a broken record. All three in 2021 led with the same headline: “Reports highest revenue of any quarter in company history.”

Connecticut-based XPO is one of those massive companies you’ve never heard of. It owns or brokers a fleet of delivery trucks that rivals UPS and FedEx, and operates America’s second largest logistics business, with clients like Target, Verizon, Walmart, and Asos. XPO has its fingerprints up and down the supply chain, from air and ocean freight to port trucking, warehousing, long-haul trucking, and doorstep deliveries. If a customer wants to return an item, XPO manages logistics for that, too.

The company as it is today was created in 2011, when current CEO Bradley Jacobs bought Express-1 Expedited Solutions, a small logistics outfit with the stock ticker XPO. Jacobs renamed the company and built it up with aggressive acquisitions and productivity-boosting automation—the value of XPO’s shares is up 1,554% since 2011. The pandemic hasn’t hurt it, either: Since lockdowns ended, supply chain chaos has been a huge boon to XPO’s business.

But XPO’s success is paralleled by a history of worker exploitation. The company has racked up 120 unfair labor practice charges in the US, faces allegations of disregard for worker safety during the pandemic, and had to pay out a $30 million settlement to truck drivers in California. In 2018, XPO was the subject of a damning New York Times investigation on unyielding, strenuous working conditions that resulted in miscarriages at one of its warehouses.

In August 2020, a consortium of unions called XPO Global Union Family published a 24-page report detailing accusations of labor violations by XPO, ranging from working conditions that forced drivers to live in their trucks, to wage theft, safety hazards, and lax covid precautions.

“The New York Times article paints a wholly inaccurate picture of our workplace,” Joseph Checkler, vice president of public relations at XPO, said in an email, adding that the company launched an investigation into the miscarriage allegations and has since developed a pregnancy care policy. Of the union report, Checkler said, “the document circulated by the unions repeats wholly inaccurate allegations that have been entirely debunked by XPO.”

As shortages of truck drivers and warehouse workers contribute to bottlenecks in the supply chain, companies like XPO may be forced to improve working conditions. But Jacobs is keeping his eye on the bottom line.

“In my letter last year, I said I was a pragmatic bear in the short-term, a bull in the mid-term, and a mega-bull in the long-term,” the CEO wrote in his April 2021 letter to stockholders. “Well, the bear has left the building and the bull has arrived ahead of schedule.”

By the digits

44%: Year-over-year increase in XPO’s second-quarter 2021 revenue

107,000: XPO’s global employees in 2020, before the company spun off a piece of its business to GXO Logistics in August of this year

$21.8 million: 2020 compensation for CEO Bradley Jacobs (pdf, p. 55)

$34,663: Median salary at XPO

80,000: Truck driver shortage in the US

11 million: XPO’s last-mile deliveries per year

40%: Share of beers delivered to UK pubs by XPO Logistics

XPO’s labor issues

In October 2021, XPO agreed to pay nearly $30 million to settle class action lawsuits filed by 784 port truck drivers classified as independent contractors. The drivers claimed that XPO’s contracting practices resulted in them being paid less than legal wages as the supply chain crisis worsened traffic at ports. Poor driver retention contributes to the supply chain crisis as qualified drivers leave for jobs with better pay and working conditions.

James P. Hoffa, general president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, a truckers’ union, draws a straight line between the working conditions at XPO and the port trucker shortage, while XPO’s Checker says independent contractors can apply for full-time jobs at XPO.

XPO’s competitors

- UPS (based in Atlanta, Georgia) delivers 16 million packages a day.

- C.H. Robinson (based in Eden Prairie, Minnesota) was founded in 1905.

- J.B. Hunt (based in Lowell, Arkansas) operates 12,000 trucks.

- DHL (based in Bonn, Germany) invented transporting cargo papers by plane.

- FedEx (based in Memphis, Tennessee) was short 90,000 workers last quarter.

Person of interest

Bradley Jacobs, CEO of XPO Logistics (and spinoff GXO Logistics)

Jacobs studied math and jazz piano, but turned out to have an eye for unglamorous industries ripe for profit. He dropped out of college and started chartering ships to cart oil to Europe from Nigeria and Russia. From there he turned to waste-hauling in the US, then heavy equipment rentals. In 2011, he got into logistics.

At XPO, Jacobs is shaping up to be a modern railroad baron for trucking—a billionaire dealmaker who built XPO up to draw comparisons to Amazon, and pulls in CEO pay 629 times XPO’s median salary. This year, Jacobs was up for an $80 million payout, loudly opposed by the truckers’ union, and ultimately struck down by shareholders. That vote, however, is non-binding.

Keep learning

- XPO Logistics will close warehouse where some pregnant workers miscarried (NYT)

- From sapling to pure-play LTL: The story of XPO Logistics under Jacobs (Transport Dive)

- ‘A dark legacy’: Unions voice fears over global logistics firm’s spinoff (The Guardian)

- XPO Exposed (XPO Global Union Family)

- Better than Amazon? How Bradley Jacobs turned a $63M bet into a $12 billion transportation empire (Forbes)

- Bradley Jacobs has acquired more than 500 companies. Here’s what he has learned. (WSJ)

Have a non-exploitative end to your week,

—Aurora Almendral, senior reporter (obsessed with logistics, but can’t drive a truck)

One 🕵️ thing

The body of Jimmy Hoffa, the former Teamsters union boss who disappeared 46 years ago—and father of recent Teamsters president James P. Hoffa—still hasn’t been found. In October, the FBI dug up a former landfill in New Jersey after a deathbed confession from a man who claimed to have buried him there, inside a steel drum.