Hi Quartz members,

In the near-ish future, tech companies are betting their customers will spend a good chunk of time immersed in virtual worlds. This gamble on the so-called metaverse drove the late Facebook to change its name, prompted Nike to buy a company that makes custom virtual sneakers, and spurred the city of Seoul to start offering public services through a virtual city hall.

Likewise, when Microsoft bought gaming giant Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion this month, executives name-dropped “the metaverse” more than 10 times on a call with investors. The company isn’t only thinking about gaming, either: In November, Microsoft announced plans for a more immersive version of its Teams workplace software.

If the Activision deal is approved by regulators—no small if—it will be Microsoft’s biggest acquisition ever, with a price tag higher than its last three purchases combined. Owning Activision would give Microsoft, which owns the Xbox gaming console, control over franchises that include Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, and Overwatch, potential key pieces of its $10-a-month unlimited Game Pass. Microsoft would also inherit high-speed cloud technology essential for making augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) experiences accessible anywhere. Perhaps most important, the deal sets up the next big battle in consumer tech: between Microsoft and Meta, for command of virtual worlds where people play and work.

It’s a fitting rivalry. Microsoft, once a Big Tech villain and the poster child for antitrust backlash, has improved its image over the past decade—but in a mobile-first world, the company also lost some of its edge. Meta, today’s Big Tech villain and antitrust poster child, has plenty of cutting-edge ideas, but is struggling to distract regulators from its influence, and users from its shoddy reputation. Both companies are worried about losing ground with young people.

For now, at least one thing is clear: Back in September, Facebook said the metaverse isn’t “a single product one company can build alone.” Microsoft buying Activision guarantees it won’t be.

A brief history of Activision

1979: Activision is founded by four programmers at Atari who left the gaming console company over pay. They went on to develop games like Pitfall, Chopper Command, and Skiing for the Atari console.

1990: Software entrepreneur Bobby Kotick and partner Brian Kelly buy Activision, which had been renamed Mediagenic, for less than $500,000. The company is $30 million in debt, with $2 million in assets.

1999: Activision brings on Neversoft Studios to develop Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater. It’s the company’s first hit, becoming a $1 billion franchise and spawning multiple spin-off games.

2003: Activision releases Call of Duty, a first-person shooter game set during World War II. It ultimately becomes the company’s most profitable franchise, generating $27 billion in sales to date.

2008: Activision merges with Vivendi Games to form Activision Blizzard, acquiring the massive multiplayer game World of Warcraft.

2009: Kotik draws flak for being out of touch after suggesting in a Forbes profile that he doesn’t play the games his company produces.

2013: Activision splits from Vivendi in a buyout worth $8.2 billion.

2021: The California Department of Fair Employment and Housing sues Activision, alleging the company fosters a “fratboy workplace culture” rife with sexual harassment, unequal pay, and retaliation. Employees later sign a letter calling Activision’s response to the lawsuit “abhorrent and insulting.”

2022: Microsoft acquires Activision, an interest reportedly prompted by the gaming company’s failure to address internal complaints. Kotick is expected to depart once the deal is finalized.

Fixing Activision from within

Activision’s toxicity has been festering for years; ahead of the Microsoft deal, both employees and shareholders (pdf) were sounding increasingly loud alarms. Fortunately, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella knows a thing or two about turning around company culture.

When Nadella took over in 2014, Microsoft was known for bureaucracy, suspicion, and short-sighted quarterly goals. The company was also cutthroat, and shied away from the open-source approach long considered central to the developer community. In short order, Nadella, who had been with Microsoft since 1992, started pushing a different mindset:

- The company started working with rivals, launching Microsoft Office on the iPad, and joining forces with Linux.

- Nadella introduced a week-long annual employee conference, including a three-day hackathon where employees work on projects outside their daily job role.

- Microsoft got rid of stack ranking, a performance review system that required managers to give some negative reviews, regardless of performance.

- Nadella embraced accountability, acknowledging both his and Microsoft’s lackluster track record on diversity and inclusion.

Activision’s culture is in dire need of the Nadella touch, and the company is already cleaning house. Activision fired more than three dozen people over misconduct allegations, and Kotick is unlikely to be kept around. Activision employees are cautiously optimistic.

By the digits

$68.7 billion: Microsoft’s bill for Activision

$390 million: Kotick’s potential payday, thanks to his 3.95 million Activision shares

9,500: Activision Blizzard employees

100 million: Players of Call of Duty, the studio’s most popular gaming franchise

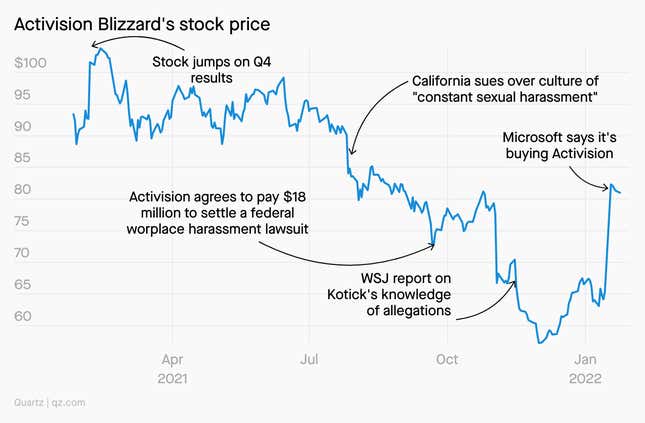

$18 million: The settlement Activision paid last year over a sexual harassment and discrimination lawsuit brought by the US government

38%: 1-day increase in Activision’s stock price following the Microsoft news

What to watch for

🔒 “Exclusive to Xbox.” Microsoft could throw a lot of money at Activision games, but it could also limit them to Xbox consoles. For now, Activision has pre-acquisition commitments to make the next few Call of Duty games available on Sony’s PlayStation.

⚔️ Speaking of PlayStation… Tokyo-based Sony will need to figure out how to keep its gaming console competitive, while also sussing out its own role in the brewing metaverse duopoly.

⏰ Game release schedules. Kotik was known for enforcing a punishing Call of Duty release schedule—a new game every year—which contributed to Activision’s intense culture. There is already talk of slowing things down.

👀 Privacy and antitrust. The Activision deal gives Microsoft access to even more data—a challenge for privacy rights—and is also likely to earn antitrust scrutiny.

✊ Unionization. A group of Activision quality assurance testers have been pursuing organizing; those efforts will probably be more difficult under Microsoft.

🇨🇳 The China conundrum. In 2019, Activision suspended a Hong Kong gamer after he voiced support for protesters; in 2021, Microsoft shuttered LinkedIn China over censorship and compliance concerns. Courting China’s internet users isn’t getting any easier.

😍 Pretty please? Not every Activision hit is a war story. Microsoft could revive some of the gaming company’s classics, including Guitar Hero and Crash Bandicoot.

Keep learning

- Activision fired problem staff before $70B Microsoft takeover (Quartz)

- Microsoft’s Activision Blizzard deal is a major metaverse play (Quartz)

- Look out, Fortnite: Call of Duty is entering the battle royale market (Quartz)

- At Activision, a hero and villain, zapped into one (New York Times)

- Sony’s video game strategy challenged by Microsoft’s deal for Activision (Wall Street Journal)

- A guide to Microsoft’s Xbox game studios empire (The Verge)

- Microsoft can rescue a historic trove of lost games from Activision’s vault (Mashable)

Thanks for reading! Don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a gamified end to your week,

—Courtney Vinopal, breaking news reporter (Candy Crush novice)

—Ananya Bhattacharya, tech reporter (prefers IRL blizzards to online gaming)