Hi Quartz members,

Prologis, a San Francisco-based industrial real estate firm, is the undisputed king of the warehouse world. The company rents out 1 billion square feet of warehouse space to thousands of tenants across four continents—including Amazon, which counts Prologis as its biggest landlord. Until last year, no other industrial landlord came close to matching Prologis’s prodigious holdings.

But lately, private equity firms, including Blackstone and KKR, have started muscling their way into the warehouse market. They’re quickly building up industrial real estate portfolios to rival the warehouse king. For the first time since Prologis climbed atop the industry in 2011, it’s facing a serious challenge from its competitors.

The competition has been fueled by the pandemic, which turned warehouses into one of the world’s hottest commodities as quarantined customers shifted to online shopping and supply chain snarls led to stockpiling. The winner of the warehouse race will reap the profits that come with renting key infrastructure to the booming e-commerce sector—and the rent prices these industrial landlords set will have an impact on the prices shoppers pay for everything they order online.

Charting the booming US warehouse market

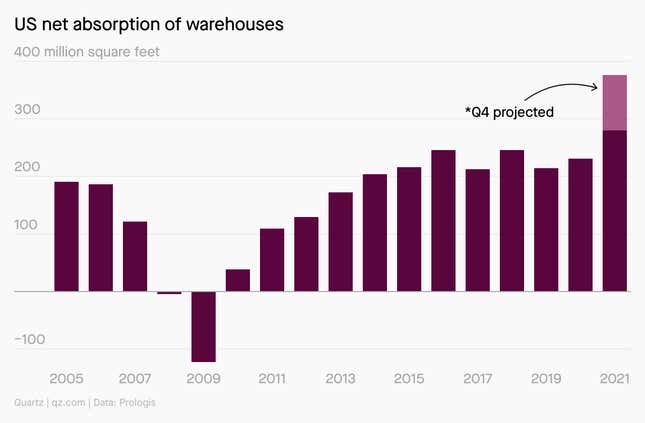

One way to gauge demand in real estate is to look at a sector’s “net absorption rate,” which measures how many square feet of property became occupied in a given year, minus the number of properties that became vacant. When net absorption is high, it means lots of owners are buying up properties and putting them to use. Last year, net absorption in the US logistics sector, which includes warehouses, hit record highs.

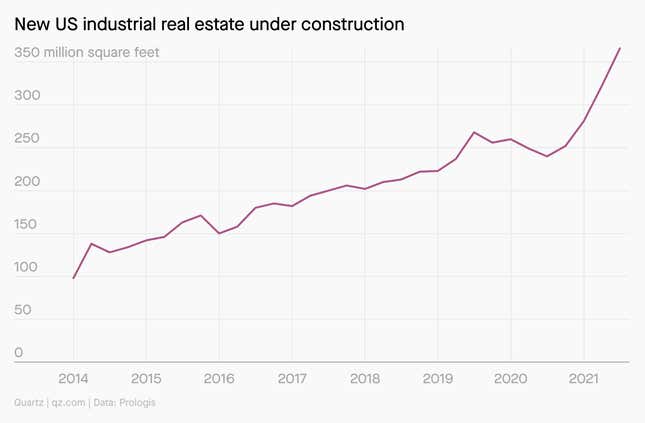

Although new warehouse construction is booming, supply can’t keep up with demand. US warehouse vacancies hit a record low of 3.9% in the third quarter of 2021, meaning that industrial real estate was “effectively sold out,” according to a report from Prologis. That has led to worries about a warehouse shortage in the US. Tight supply fueled a 7.1% hike in warehouse rents between July and September 2021, according to Prologis data.

By the digits

$215 billion: Value of Prologis’s real estate holdings

5,800: Tenants who rent from Prologis

13%: Fraction of Amazon’s warehouse space owned by Prologis in 2017

19: Countries in which Prologis operates

$2.2 trillion: Economic value of the goods that moved through Prologis warehouses in 2020, which Prologis estimates adds up to 3.5% of the GDP of the countries in which it operates

Person of interest

Prologis CEO Hamid Moghadam grew up in Iran as the son of a real estate developer during the country’s economic boom in the 1960s. At 16, he started studying civil engineering at MIT, intending to return home and work in real estate. But in 1978, between the time that Moghadam finished his master’s at MIT and enrolled in an MBA program at Stanford, the Iranian Revolution changed the trajectory of his life: With his Western education and secular worldview, he felt he couldn’t go back to Iran.

Instead, in 1983, Moghadam launched a real estate firm in San Francisco called AMB, which initially invested in office space and shopping centers on behalf of big institutional investors. But during the dot com boom of the 1990s, Moghadam became convinced that e-commerce would be the future of shopping. AMB sold its offices and shopping centers and went all-in on warehouses and distribution centers. (Much to Moghadam’s chagrin, AMB also invested $5 million in a doomed online grocer called Webvan—and passed up the chance to invest in Amazon. “We got the company wrong, but we got the big trend right,” he later told The Economist.)

Over the next decade, AMB became one of the biggest warehouse landlords in the US. In 2011, amid the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis, Moghadam orchestrated a deal for AMB to buy its larger but struggling rival ProLogis and create the biggest industrial real estate company on Earth. The new firm, subtly rebranded as “Prologis,” would continue to grow thanks, in part, to the monstrous success of its biggest tenant, Amazon.

Quotable

“We are focused on the markets where there are large numbers of people and there’s lots of money in their pockets. You rob a bank, because that’s where the money is. Where do you have consumption? Where people are.”

—Hamid Moghadam on Prologis’s strategy of placing warehouses as close as possible to the center of dense, wealthy cities

Prologis vs. Blackstone: a battle of titans

In 2011, when Prologis finalized the merger that would cement its status as the world’s largest warehouse landlord, Blackstone was only just beginning to buy industrial real estate. But over the next decade, the private equity firm expanded aggressively. In 2019, Blackstone real estate head Ken Caplan said warehouses were the firm’s “highest conviction global investment theme.” Blackstone now owns about 950 million square feet of warehouse space, putting it within striking distance of Prologis.

Blackstone’s meteoric rise sets up a showdown between the encroaching private equity firm and the long-time warehouse champion. Blackstone argues its warehouse business has an edge because the firm can leverage the data from all of Blackstone’s other businesses to make better investment decisions. Blackstone invests in nearly everything under the sun: biomedical research, digital payments, autonomous robots, power plants, motel chains, dating apps, and a slew of amusement parks including SeaWorld and Legoland. “We operate as one globally connected business and we have a constant view into what’s happening in the markets and our portfolio,” Caplan has said.

But Prologis is betting the prime real estate it bought before others entered the market will give the company a lasting advantage over rivals. “The new supply that comes online is farther from city centers and less competitive than the standing stock,” said Cris Caton, who heads strategy and analytics at Prologis.

Although the companies are sparring for dominance, the warehouse industry is growing so fast that there is room for more than one global player. The fiercest competition will center around control of the most valuable warehouses nearest to the center of the wealthiest cities.

Keep learning

- Corporate landlords like Blackstone are riding this inflationary wave all the way to the bank (Quartz)

- Snarled Supply Chain Is Making U.S. Warehouse Shortage Worse (Bloomberg)

- Why Blackstone and other private equity giants are gobbling up warehouses (Pitchbook)

- Warehouse shortages will stay with us until 2023 as inventory gows (The Loadstar)

- Warehouse woes driven by labor shortage, not capacity scarcity (Journal of Commerce)

- The e-commerce boom makes warehouses hot property (The Economist)

- Blackstone has become one of the biggest warehouse landlords on Earth (Quartz)

Have a fulfilling end to your week,

—Nicolás Rivero, tech reporter (running out of storage space for books he hasn’t read)

One 🌆 thing

To squeeze as much warehouse space as possible into the hearts of major cities, Prologis is pioneering the design and construction of multistory warehouses and getting creative about converting abandoned buildings into e-commerce fulfillment centers:

🏙️ Seattle: Prologis built the first multistory warehouse in the US, a three-floor facility just outside downtown Seattle.

🐎 Portland: The firm converted the shuttered Portland Meadows horse racing track into a 1.8 million-square-foot industrial park.

🏬 New York City: It turned a Bronx outlet store for ABC Carpet & Home into an Amazon fulfillment center.

🛍️San Francisco: Prologis bought the 1.1 million-square-foot Hilltop Mall with plans to convert it into warehouse space.