Hi Quartz members,

The global economy is building a ravenous appetite for hydrogen gas. And an outspoken Australian billionaire is angling to serve it up, perhaps minting another fortune in the process.

Today, hydrogen is mainly used to produce fertilizers, refine oil, and process foods. But many policymakers and entrepreneurs hope to see it used much more widely in the future, as a low- or zero-carbon alternative to fossil fuels in heavy-duty transportation and industrial processes like steel manufacturing. By 2050, global hydrogen demand could grow sixfold, according to the International Energy Agency, and provide 10% of total global energy consumption.

Whether this is really a win for the climate depends on how the hydrogen is manufactured. Today, nearly all hydrogen is derived from natural gas and coal, and ultimately yields more emissions than the fuels it is meant to replace. So-called “green” hydrogen—produced by using solar- or wind-generated electricity to split hydrogen atoms out of water—emits nothing but water vapor, but today is produced only at small experimental scales. The trouble is cost: Because of the price of renewable energy and electrolyzer machines, green hydrogen is up to three times more expensive than “grey.”

But the price of producing green hydrogen is falling, and as governments crack down on high-pollution sectors, demand for it is heating up. Enter Fortescue Future Industries, a fledgling offshoot of Australian mining giant Fortescue Metals Group (FMG). Its goal is to be the world’s top exporter of green hydrogen and to make it, as the company puts it, “the most globally-traded seaborne energy commodity in the world.”

In the 2010s, FMG became a huge overnight success by leaping into the iron ore market just as steel factories in China developed an insatiable demand for it. Now, founder and chairman Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest wants to repeat the feat with hydrogen. The economics of hydrogen exports are harder than iron, and it could be decades before there’s a significant global market. But the company is already building its own electrolyzers and “gigafactories” in Australia, financing others abroad, inking deals for advance sales, and snapping up smaller technology companies—paid for out of profits from the legacy iron business.

“If and when green hydrogen really takes off,” said Robin Griffin, a vice president of energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, “companies like FFI will do extraordinarily well.”

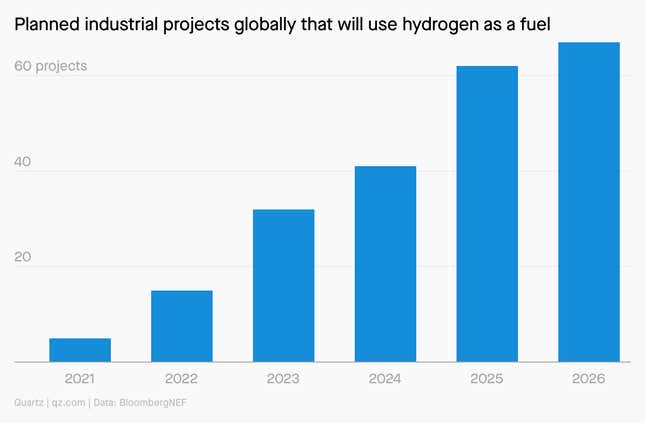

Charting: Hydrogen-hungry factories

As countries build more industrial facilities that use hydrogen as fuel, demand for it is likely to grow.

By the digits

- 500 million: Upper estimate of metric tons of hydrogen that will be in demand by 2050, up from 90 million today.

- 15 million: Metric tons of green hydrogen that FFI aims to produce annually by 2030.

- 10%: Planned capacity of green hydrogen electrolyzers that are scheduled to come online by 2030, compared to what is needed in IEA Net Zero forecast.

- 22: Countries that are expected to publish official hydrogen adoption strategies in 2022, including the US, Brazil, and China.

- 23: Countries in which FFI is researching hydrogen production deals.

- $17.8 billion: Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest’s net worth.

- $10 trillion: Value of potential global market for green hydrogen by 2050, according to Goldman Sachs.

Fortescue’s future fortunes

Forrest may have no shortage of ambition (or cash), but it will take more than that to prove his hydrogen dreams are more than hot air. Here’s what FFI has going for it, and against it, as it tries to become a leading green hydrogen exporter.

Advantages:

☀️ Cheap renewable energy: One key to cheap green hydrogen is cheap wind and solar power, and Australia has more of that than just about any other country.

🇨🇳 Proximity to Asia: China, South Korea, and Japan are all expected to be major hydrogen importers, which could be largely supplied by Australia.

🔩 Existing business ties to steelmakers: FMG has plenty of contacts and experience in China’s steel industry, which is likely to be a vital future customer for green hydrogen.

🚜 In-house demand: FFI’s first customer is itself; the company is prototyping hydrogen-powered mining trucks for its iron operations and aims to replace its entire fleet by 2030.

Disadvantages:

🚢 High seaborne shipping costs: Shipping liquified hydrogen, which requires supercooled tanks, is more expensive than delivering it via pipeline, especially all the way from Australia. FFI aims to get around this by building electrolyzers in other countries with favorable renewable energy costs, like Argentina.

🧐 Uncertain future market: Today the green hydrogen market is essentially nonexistent. FFI’s fortunes hinge entirely on a rapid, massive overhaul of the energy system that may or may not come to pass in the next couple of decades, depending on whether countries pass more legislation to support their climate goals and how quickly the costs of manufacturing electrolyzers and generating renewable energy come down.

⏰ Tricky timing: To have sufficient green hydrogen production and distribution in place by the time demand is expected to pick up later this decade, companies need to make large capital investments now, before green hydrogen has become cost-competitive. FFI’s CEO Julie Shuttleworth sees it this way: “Lots of people aren’t making green hydrogen because no one’s buying it, and no one’s buying it because no one’s producing it. We can get that started, so when there’s strong demand we’re ready to supply it.”

A brief history

- 1993: Forrest becomes CEO of Anaconda Nickel.

- 2001: Forrest is ousted after the company nearly goes bankrupt.

- 2003: Forrest takes control of iron ore mining company Allied and renames it Fortescue Metals Group.

- 2008: FMG makes its first commercial shipment of iron.

- 2017: FMG becomes world’s fourth largest iron ore producer, the position it holds today.

- 2020: FFI founded.

- Jan. 2022: World’s first liquid hydrogen tanker sails from Australia to Japan.

- 2027: When green hydrogen is projected to be cost-competitive with fossil fuel-based hydrogen in Australia.

- 2030: Year by which FFI aims to export 15 million metric tons of green hydrogen.

Battle of the billionaires

Andrew Forrest isn’t the only billionaire eyeballing green hydrogen. Mukesh Ambani, one of Asia’s richest people, who like Forrest built his fortune in old-school commodities (oil refining, in his case), said in January that he will spend $75 billion on renewable energy systems in India, with a special focus on green hydrogen.

“The two most aggressive, ambitious, visionary entrepreneurs in India and Australia have both come up with the same idea,” says Tim Buckley, an energy economist in Australia. “They’ve both drunk the same Kool-Aid.”

Like Forrest, Ambani sees green hydrogen not just as a product to sell, but as a means to decarbonize other parts of his business, the industrial conglomerate Reliance Industries—particularly for producing fertilizer and refining oil. Ambani is also repurposing some existing factories to produce “blue” hydrogen from natural gas. He’ll have the support of the Indian government, which is keen for an alternative to spending billions of dollars subsidizing imported fertilizer.

Forrest’s long-term view is more global—but if all goes according to plan, there should be enough of a market to share.

“Twiggy is an entrepreneur used to doing things that everyone else says can’t be done,” Buckley says, “and doing it at a scale that is mind-bogglingly ambitious.”

Keep learning

- The natural gas industry is making a risky bet on hydrogen (Quartz)

- China is beating the world on yet another climate technology (Quartz)

- Hydrogen will help Russia maintain its energy strangehold on Europe (Quartz)

- Financing the future of green hydrogen (Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis)

- The green hydrogen economy (PwC)

- Global hydrogen review 2021 (International Energy Agency)

- 10 predictions for hydrogen in 2022 (Bloomberg)

Have a great end to your week,

—Tim McDonnell, climate and energy reporter (hoping to take a reporting trip to Australia 😎)

One ❄️ thing

Like natural gas, hydrogen must be liquified before it can be shipped overseas. But that chemical reaction requires cold conditions: -252.87° C, to be exact, just a few degrees shy of “absolute zero,” the theoretical temperature at which atoms are completely still. Natural gas requires only a balmy -160° C.

Reaching that temperature is possible, as a small Japanese freighter proved in January. But maintaining it across a sprawling network of hydrogen ships and terminals, as FFI hopes to see, will be expensive, especially since some product is inevitably lost in transit, reducing the profit a company can make from a given shipment. Shipping expenses could potentially double the cost of green hydrogen coming from Australia, even after electrolyzers become cheaper.

One solution FFI is considering is to scatter factories around the globe, closer to points of use. Another is to skip the freeze headache and export hydrogen after it has been converted to ammonia (liquid below -33° C). That can be cost-effective if the customer, such as a fertilizer factory, actually wants ammonia as the end product. But if they really want hydrogen, converting ammonia all the way back might not be worth it. FFI is betting that either way, they can still get it delivered for less than rival producers.