Hi Quartz members,

Maersk was once the world’s largest shipping line. But now it sees itself as so much more: Maersk is an airline, a trucking fleet, a port operator, a warehouse landlord, a last-mile delivery company, a customs brokerage, a freight booking platform, and a logistics software developer. It is, in short, a one-stop logistics shop with aspirations to take a piece of every step of the supply chain.

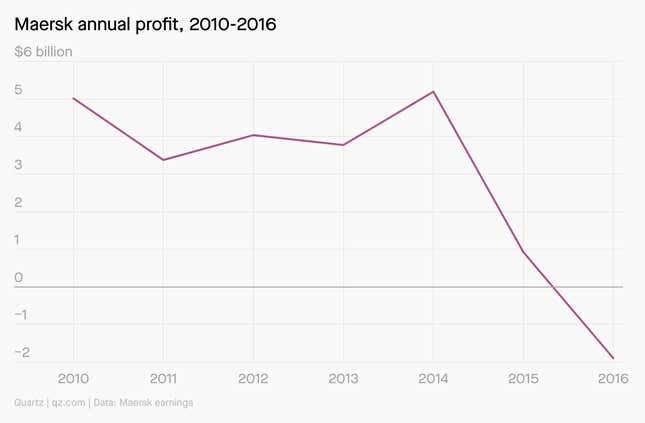

Maersk’s expansive ambitions date back to 2016, a dark year for ocean freight. Shipping profits are always low, but that year, slowing economies in Europe and China, along with an increase in the supply of ships, caused global freight rates to tank. Maersk lost nearly $2 billion. So in September, the company decided to expand beyond the hardscrabble world of shipping to focus on more lucrative parts of the supply chain.

As Maersk built up its land- and air-based operations, it gave up its dominion over the sea. In January, Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) became the world’s biggest shipping line by container capacity, unseating Maersk for the first time in 25 years. But Maersk CEO Søren Skou was unfazed, telling Bloomberg the company was happy to cede market share in ocean shipping while it grows its logistics operation on land, where its profit margins are higher.

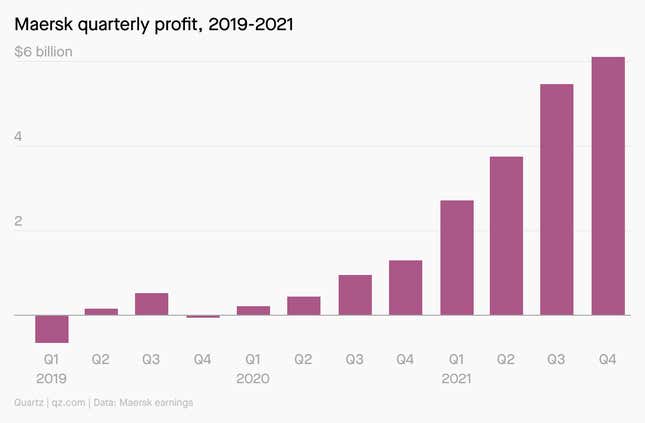

Now, the pandemic has turbocharged Maersk’s transformation. Soaring ocean freight rates have generated billions of dollars in profits, which Maersk is using to buy a string of logistics companies. If its gambit pays off, Maersk will have traded its position as the biggest ocean carrier to become the first all-in-one supply chain company. Clients would be able to outsource their entire delivery operation to Maersk, which would transport their products from the factory loading dock all the way to their customers’ doorsteps.

By the digits

$18 billion: Maersk’s profit in 2021

-$44 million: Maerks’s profit in 2019

738: Ships in Maersk’s fleet

1 million: Containers Maersk moves each month

6: Average minutes that pass between Maersk container ships calling at some port in the world

$1,883: Maersk’s average freight rate per 40-foot container in 2019

$3,318: Maersk’s average freight rate per 40-foot container in 2021

How Maersk is spending its pandemic profits

Maersk has made $21 billion in profits during the pandemic—and now it’s starting to spend that cash. Since Maersk’s hot streak began in 2020, it has bought:

📦 4 e-commerce fulfillment companies in Europe, Asia, and the US, bringing its total collection of warehouses and distribution centers to 549

🚚 Pilot Freight Services, one of the biggest trucking companies in North America

⚖️ 2 customs brokerages in the US and Europe

✈️ 2 new Boeing 777 cargo jets to add to its budding cargo airline’s existing fleet of 15 planes

🔋 16 new electric trucks to add to its fleet of 215 vehicles

🚢 8 carbon-neutral ships for $1.4 billion

🤝 Senator International, a “freight forwarder” that acts as a broker between shipping companies like Maersk and their customers

💸 Its own stock—$5 billion worth—in a massive share buyback scheme announced in May

Quotable

“Regulators will need to play catch-up, because we don’t want the shipping lines to be the next Facebook or Amazon; it’s a wake-up call for the European Community.” —James Hookham, director of the Global Shippers Forum, a trade group that represents the customers of shipping lines and cargo owners

If Maersk successfully transforms itself into a one-stop supply chain shop, it will fundamentally change the way the logistics industry works. Traditionally, small businesses rely on middlemen known as freight forwarders to book space for their cargo on ships, planes, trucks, trains, and delivery vans all owned by different companies. Maersk wants to cut out the freight forwarders and sell all those services directly to small businesses—which Maersk argues will make the industry more efficient and lower costs.

But it’s a risky move: Maersk still gets much of its business from freight forwarders, and they aren’t happy about Maersk’s efforts to usurp them. The European Association for Forwarding, Transport, Logistics, and Customs Services, an industry group that represents freight forwarders, has called for European competition regulators to investigate Maersk for trying to establish a logistics monopoly.

Godzilla vs. Kong for supply chains

There’s an unlikely rival on the horizon set to challenge Maersk’s control of global supply chains: Amazon.

While Maersk is expanding from cargo shipping to last-mile delivery, Amazon has been building its logistics network in the opposite direction. The e-commerce giant has long since dominated trucking, warehousing, and last-mile delivery; now, Amazon is building up a cargo airline, chartering cargo ships, and making its own shipping containers. Analysts have begun to speculate that Amazon could soon start selling its own all-in-one logistics service to rival Maersk’s.

Over the next decade—if these trends hold—Amazon and Maersk’s ambitions could start to overlap. “It’s creating this battle between these two very different beasts that will probably come to a head at some point in the next couple of years,” says Eytan Buchman, who heads marketing at the freight booking platform Freightos and has written about Maersk’s pivot away from shipping.

Colliding ambitions

As Maersk reinvents its business model, the company is also working toward another transformative ambition: making its entire business carbon neutral by 2040. In January, Maersk announced that it planned to hit net zero a decade earlier than it had before, putting its climate goals well ahead of rivals like MSC, CMA CGM, and Hapag-Lloyd. Maersk hopes to use its green veneer to market its services to clients that have set their own aggressive 2040 climate goals, like IKEA and Patagonia.

The trouble is, Maersk’s ambition to build a globe-spanning airline runs counter to its carbon-cutting goals. Air cargo releases 22 times more carbon dioxide than ocean shipping for each ton of goods transported—and there’s no clear way to cut plane emissions. Sustainable aviation fuels are still early in their development and may not be widely available for another decade. Maersk’s investments in air freight shows “they’re not really serious about tackling the climate emergency,” said Lucy Gilliam, senior policy analyst for Seas at Risk, an environmental organization.

Full steam ahead

Shipping is far from the only industry undergoing transformational change. In the first chapter of our new series, The Next 10 Years, we look at other disruptive forces, including:

- The emergence of a new class of robot. “I’m convinced that robots are becoming sophisticated enough to be the teammates that I hoped for as a child,” one robotics expert told Quartz.

- The end of live events as we know them. Audiences of the future won’t just be in person, or just watching online, but “all of the above and at the same time.”

- The start of professional deepfakes. There’s a growing appetite for “hyper-real synthetic media” in movies, advertisements, commercials, and TikTok-inspired social content.

Keep learning

- As ocean freight rates crest, Maersk stakes its future on land (Quartz)

- Shipping giant Maersk’s shift into air freight is undermining its green ambitions (Quartz)

- Shipping lines have reached the peak of their pricing power (Quartz)

- Maersk could push the entire shipping industry to move up its climate goals (Quartz)

- Why signs of an improving supply chain are an illusion (Quartz)

- Maersk can’t find enough green fuel to power its carbon-neutral ships (Quartz)

- Shipping lines are paying workers bonuses of more than three years’ salary (Quartz)

Have a transformative end to your week,

—Nicolás Rivero, tech reporter (reinventing himself as a supply chain reporter)

One 🤖 thing

There’s one area in which Maersk has no plans to reinvent itself: autonomous shipping. The Japanese coastal shipping industry is testing the world’s first self-driving cargo ships in an effort to maintain the sector’s productivity as Japan’s workforce ages. But Maersk CEO Søren Skou says his company isn’t interested in pursuing the idea on its vessels.

“Even if the technology advances, I don’t expect we will be allowed to sail around with 400-meter long container ships, weighing 200,000 metric tons without any human beings on board,” Skou told Bloomberg in 2018. “I don’t think it will be a driver of efficiency, not in my time.”