Hi Quartz members,

Who are the people in your neighborhood? The question Sesame Street asked us half a century ago remains as relevant as ever, especially as our social lives are increasingly online. Nextdoor has become a place for people to bridge the gap between their digital social lives and their physical ones by getting to know people in their immediate vicinity. It’s the neighborhood block club gone online.

Nextdoor’s focus is hyper-locality. Its 69 million users are organized by geography, so people’s social circles on the app don’t extend beyond the few blocks or miles in their immediate area. Users must sign up with their real name and address, which the company verifies by sending a postcard in the mail. As such, it’s become a go-to place to post about missing pets, to swap used furniture, and to advertise local businesses. People can also communicate with local institutions like police and public health departments about matters of public safety. Since the start of the covid-19 pandemic, Nextdoor’s user base has grown 50%; the company now estimates that one third of US households are on the site.

But Nextdoor hasn’t made social media more like the neighborhood—instead, it’s put the neighborhood online.

That’s come with problems. In the US, Nextdoor has developed a reputation for its permissiveness around racial profiling, especially in posts about safety and crime. It’s also struggled with covid misinformation during the pandemic, a problem the company wasn’t at first equipped to handle.

Even though Nextdoor has taken pains to brand itself as the “kinder” social media app (really, its stock ticker is $KIND), it still remains to be seen whether its efforts will be enough to make all users feel included.

By the digits

11: Countries where Nextdoor operates

230,000: Nextdoor community moderators

36 million: Weekly active users

$4.3 billion: Nextdoor’s valuation on the day it went public in Nov. 2021 via SPAC

$2.3 billion: Nextdoor’s valuation at the time of publishing

54%: Nextdoor users who don’t mind if their neighbors leave up holiday decorations past Jan. 1

$97,000: Average household income for a Nextdoor user in 2021 (compared to $88,000 US average)

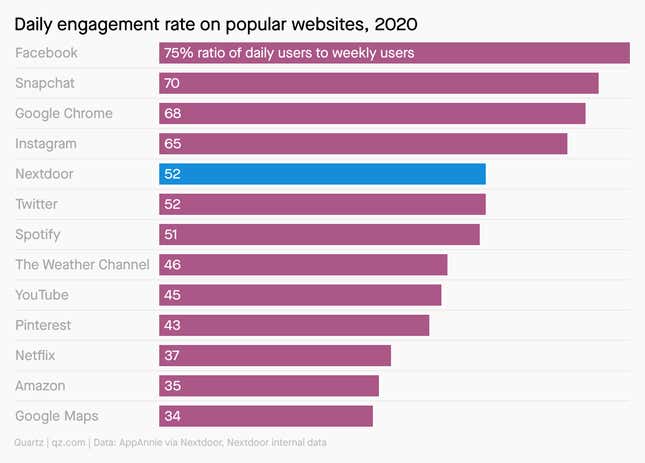

Charting how people use Nextdoor

Nextdoor isn’t the biggest social media app in the world, but it’s not striving to be. Yes, its user base is sizable in the US and other Western countries where it operates, but more importantly, it’s loyal. In 2020, just over half of its weekly active users were also daily active users.

Nextdoor IRL

Among social media platforms like Facebook and Citizen that are designed to bring communities together, Nextdoor most often blurs the line between digital life and real life. It has had a demonstrable effect on the politics, economics, and culture of neighborhoods, towns, and cities. Here are a few examples.

🤝 Politics. Political discussions on Nextdoor can get heated, so the company has steered people in the US away from discussing national politics. But the same isn’t true for local political actions—the platform encourages those. Users have organized voter registrations and meet-and-greets with mayoral candidates. But Nextdoor has still run into issues getting tangled up in politics: One town in Michigan sued the platform over misinformation about a local ballot measure.

🚨 Policing and crime. Nextdoor allows users to report instances of suspected crime on the platform and previously let them forward posts to police (a practice it ended in 2020). But beyond that, Nextdoor has pursued partnerships with local police departments to help them increase their presence on the site and further public trust of law enforcement. Police departments regularly post safety alerts, have held community events, and even hosted town hall meetings on Nextdoor.

🏘️ Small business. More than 2 million local businesses have pages on Nextdoor. They use the platform’s suite of advertising products, as well as word-of-mouth advertising from user recommendations to grow their businesses. According to Nextdoor, 88% of users shop at local businesses, and two thirds of users share recommendations with other neighbors on the site. Nextdoor allows real estate companies to advertise homes for sale or rent on the site as well.

🩺 Public health. People flocked to Nextdoor to receive crucial covid-19 information during the pandemic, but that’s also come with misinformation. Because all posts come from verified users within a community, false or misleading information can be more difficult to dismiss. “I think people take Nextdoor more seriously than Facebook,” one public information officer told Recode last year.

Nextdoor has given public health agencies a platform to share information about vaccinations and testing, and urged users to cite sources when they post about covid. But some amount of inaccurate and misleading information remains.

Brief history

2010: Nextdoor is co-founded and led by Silicon Valley veteran Nirav Tolia. Rich Barton, CEO of Zillow, is an early investor.

2016: Nextdoor expands to its first international site, the Netherlands, followed by the UK and Germany the following year. Also in 2016, following criticism from users, Nextdoor launches a new tool to reduce racial profiling in posts.

2017: Nextdoor begins offering real estate ads on its site, competing with platforms like Zillow and Redfin.

2018: Tolia steps down as CEO; former Square CFO Sarah Friar takes over.

2019: Nextdoor rolls out a Kindness Reminder to automatically flag offensive content. A report later found that the reminder caused people to change their behavior 34.6% of the time. The following year after receiving backlash during the George Floyd racial justice protests, Nextdoor launches several new initiatives aimed at promoting inclusion among users, including an anti-racism resource center and removing the “Forward to Police” feature for safety posts.

2021: Nextdoor goes public via SPAC merger, with a plan to expand into more territories.

Coding out racism?

Nextdoor’s mission has been to bring real-life communities online, but that has caused problems when it brings all the dynamics of race, class, and power with them. Over time, Nextdoor developed a reputation for allowing racial profiling, as mostly white users posted coded (and sometimes not-so-coded) messages about Black people and other people of color who they perceived as a threat, but were often simply just walking down the street or driving a car. (The company has a strict policy against racism and racial profiling on its site and has made efforts to combat it.)

It’s become such an issue that Black users have reported feeling unsafe on the platform and some have left it entirely.

Nextdoor first responded to concerns about racial profiling in 2016 by changing its algorithm to flag potential profiling language before someone posted. The company also changed the way users report crime on the website’s safety section to prevent them from using only racial identifiers without any other characteristics in describing a person. But just nine months later, reporting by BuzzFeed News found that racist posts were still an issue on the site.

Nextdoor also relies heavily on content moderation from more than 200,000 “neighborhood leads,” volunteers who neighbors nominate to oversee content on the site that gets flagged as potentially inappropriate. In late 2021, Nextdoor began offering optional webinars for moderators to better identify unconscious bias in themselves and others. (Nextdoor clarified that content reported as racist get sent directly to its internal Neighborhood Operations team, not Neighborhood Leads.)

Issues of racism in residential communities didn’t start with Nextdoor. Researchers have pointed out that the suspicion of Black and brown people in majority white neighborhoods seen on Nextdoor is a continuation of the tactics and attitudes white Americans used in earlier decades to maintain racial segregation in housing. Using Nextdoor to surveil people of color sends a message about who “belongs” in a certain neighborhood. It makes them feel unwelcome and potentially want to leave.

Nextdoor’s changes to their algorithm and community policies have stopped some of this kind of behavior on the platform, but can’t resolve these structural imbalances on their own.

Have a community-oriented end to your week,

—Camille Squires, cities reporter (newest arrival to a Brooklyn Nextdoor group)

One🪞thing

Nextdoor has been called the “anti-Facebook” for its focus on small networks and in-person communication. But the model seems to be catching. In 2021, Meta (then Facebook) launched a section called “Neighborhoods,” which looks and functions like Nextdoor, gathering news and posts on a hyper-local basis. It appears to be part of Meta’s strategy of vacuuming up successful tech models from other social media companies, but so far it hasn’t detracted from Nextdoor’s popularity.

Correction (April 4, 2022): A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the total number of global Nextdoor users (69 million, not 36 million), and misstated the year the Kindness Reminder feature was introduced (2019, not 2020). Several areas of the story have also been updated with additional context on company policies and operations.