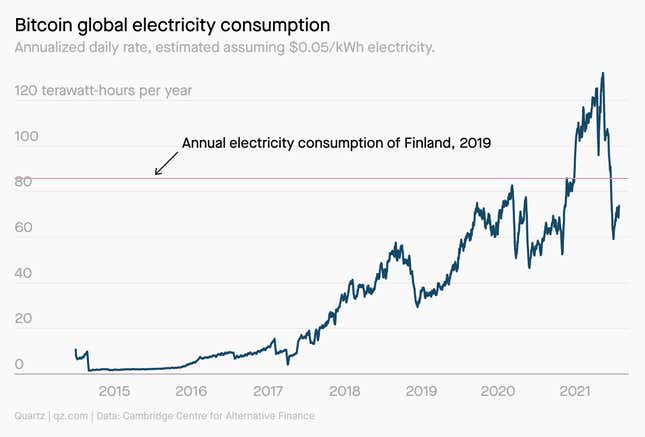

The way bitcoin and most other cryptocurrencies operate today rewards energy waste. To generate new coins, “miners” around the world operate fleets of computers that compete against one another to crack increasingly difficult math problems. Because of that escalation, miners have an incentive to work around the clock and operate as many computers as possible. The end result: Globally, bitcoin mining consumes about as much electricity as the nation of Finland, with a carbon footprint comparable to that of the London metro area.

They do so with greater fervor when the price of bitcoin rises, like it did recently when rumors swirled that Amazon may soon accept it. But its energy use could make its value less stable. Back in May, the value of bitcoin plunged after Tesla CEO Elon Musk tweeted that his company would no longer accept it as payment because of his concerns “about rapidly increasing use of fossil fuels for bitcoin mining and transactions.”

Because crypto is decentralized, it’s harder to manage its carbon footprint using regulations or carbon pricing, as governments are increasingly doing in other carbon-heavy sectors. But the crypto community—dominated by bitcoin, which about 89% (pdf) of global crypto miners work to produce—has a self-interest in decarbonizing. Not only would that dramatically reduce emissions on a warming planet, it could stabilize the price and make it more palatable as a medium of exchange for retailers and financial institutions. Is it possible? Let’s take a look.

Charting bitcoin’s thirst for energy

Since August 2014, the price of a single bitcoin has gone from about $580 to north of $38,000. The boom has drawn more miners into the game, and the industry’s electricity consumption has skyrocketed (this estimate, from Cambridge University, is based on some assumptions about the type of computers most miners use and the average price they pay for electricity relative to the price of bitcoin).

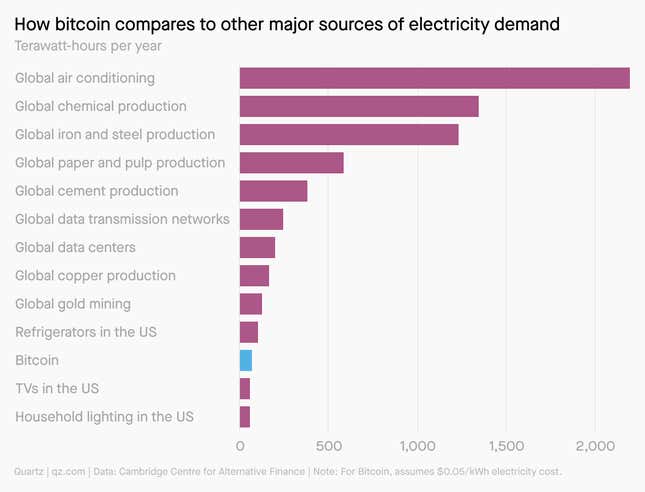

That footprint pales in comparison to other power-hungry sectors—gold mining, for example, uses far more electricity. Still, its footprint is striking considering how few applications there are for cryptocurrency at present.

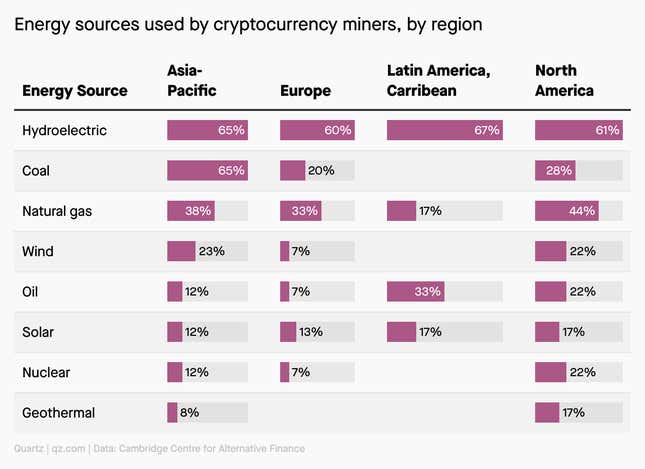

Translating this energy use into carbon emissions is tricky, but Cambridge researchers made an informed guess (pdf) about how their energy is produced based on surveys of miners and what’s common where their computers are located. Globally, three-quarters of miners use renewables for at least some of their mining—but overall, only about 39% of mining activity is powered by renewables (not counting hydroelectric dams, which are the top source of power). The upshot is that cryptocurrency’s carbon footprint is likely comparable to that of a major city in the US or Europe.

The paths to low-carbon crypto

Efforts to decarbonize digital currencies generally fall into three categories:

☀️ New energy sources: Twitter chief Jack Dorsey is a vocal proponent of bitcoin. In April his other company, the payment platform Square, published a paper (pdf) arguing that bitcoin “could enable society to deploy substantially more” renewable energy. The idea is that bitcoin mines could improve the economic feasibility of solar and wind farms by being on standby to purchase any electricity that wasn’t needed by the grid and would otherwise go to waste (since solar and wind energy output depends on the weather, it doesn’t always align with power demand).

There are a few issues with this claim. One, solar and wind are already becoming much more widespread and inexpensive without bitcoin’s help. Two, ever-escalating competition among miners means few could afford to twiddle their thumbs while waiting on available clean power (although improved utility-scale batteries could provide better continuity). Three, the reverse is also true: In the US, crypto mining has also propped up coal-fired power plants that were otherwise uneconomic, and there’s a cottage industry cropping up to help fracking companies turn extra profit from bitcoin.

Still, as the cost of renewables and other low-carbon energy sources comes down, more miners should be able to plug in to cheap green electricity.

💵 Carbon offsets: A growing number of cryptocurrency exchanges are partnering with carbon offset brokers to offer carbon-neutral crypto, and some brokers even accept cryptocurrency as payment for offsets (which usually involve forest conservation).

Unfortunately, the offset market is unregulated, and is rife with dubious assumptions, willful misrepresentations, and systematic accounting errors. A review in May of 35 prominent offset programs by Sylvera, a London-based startup that aims to be a Moody’s-esque ratings service for offsets, found that nearly half didn’t deliver what they promised.

💻 The “Merge”: Ultimately, the most promising solution is to replace the traditional computational approach to mining, known as “proof-of-work,” with lower-energy alternatives. One of bitcoin’s chief rivals, ether (a currency that runs on a platform called Ethereum), has been plotting a transition, dubbed The Merge, that its proponents say will shave off 99.5% of its carbon footprint. Under the new system, known as “proof-of-stake,” a miner’s ability to access new coins will be predicated on the number of coins they already own. That would allow mining to happen on a normal computer, not an energy-intensive fleet of servers. Some less popular coins, like binance and cardano, have already made that transition.

Coming to America

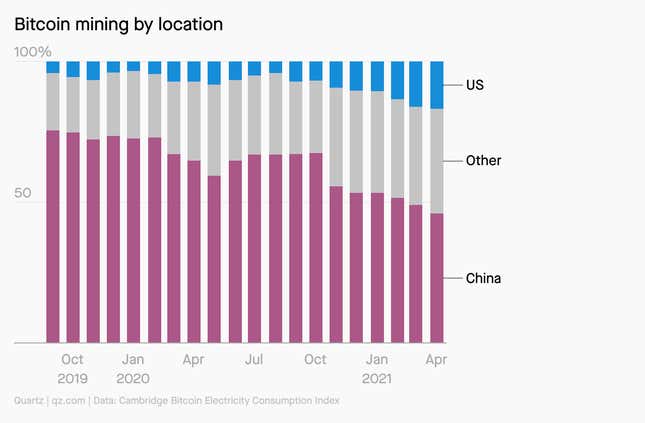

China, despite its sometimes hostile relationship with the crypto scene, has dominated the global bitcoin mining charts. But the country’s market share went into freefall this summer when the government started unplugging miners in a series of provinces, citing environmental policy.

China’s clampdown is driving an exodus of bitcoin miners to wherever they can find cheap electricity and stable crypto regulation. That could make bitcoin greener, but it depends where the miners end up. If they go to the US (America’s share of mining surged to about 17% in April, up from 7.2% a year earlier, according to the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance) there’s a better chance that their electricity will come from a renewable or sustainable source. If they go to Kazakhstan, as many others have, the power is almost certain to come from fossil fuels. In any case, as the bitcoin mining network becomes more dispersed, it will likely become more challenging for researchers to monitor its carbon footprint.

Fred Thiel, CEO of crypto mining company Marathon Digital Holdings (no relation to controversial tech investor Peter Thiel), doesn’t think the US and Canada will end up accounting for the majority of bitcoin mining. Instead, he expects mining to spread out around the planet to wherever cheap renewable energy is available, from geothermal power in El Salvador to solar power in the deserts. Places that have abundant energy but, until now, little economic reason to develop it suddenly have a reason to do so.

Reading list

How much energy does bitcoin use? (Quartz)

How bitcoin can become more climate-friendly (Quartz)

Ethereum’s recovery is tied to it becoming more energy-efficient (Quartz)

Elon Musk and Cathie Wood disagree on bitcoin’s climate impact (Quartz)

Why Jack Dorsey and Square’s case that bitcoin can be green is misguided (Slate)

Bitcoin and renewables: is cryptocurrency mining problematic? (Power-technology)

How China’s bitcoin mining ban affects energy consumption estimates (Digiconomist)

Bitcoin alternatives could provide a green solution to energy-guzzling cryptocurrencies (The Conversation)

Will bitcoin move to proof-of-stake by 2035? (Metaculus)

🔮 Prediction

Cryptocurrency, like everything else, will inexorably get greener as the world’s electric grids get greener. Ether’s proof-of-stake shift is expected by late 2021 or early 2022 and, if it works without splintering the network into rival factions, other coins may follow suit. But if a recent informal survey of bitcoin enthusiasts is any indication, bitcoin isn’t likely to switch in the near term. And the fact that so many miners are focused on carbon offsets suggests that they don’t see a complete transition to renewables anytime soon.

Sound off

Bitcoin is all about speculation, so let’s do a bit of our own.

Where will the price of bitcoin go in six months?

Into the stratosphere—the party is just getting started

Into the toilet—you’re better off lighting your savings on fire

We’re already at peak bitcoin—it will stabilize about where it is today

In last week’s poll about the metaverse, 39% of respondents said the metaverse was coming eventually. We’ll see you there.

Have a great week,

—Tim McDonnell, climate reporter

—John Detrixhe, senior economics reporter

One 🤯 thing: Glimpse into a mine

The problem with cryptocurrency mines in a single image: They’re too dang big (this one belongs to the BitRiver company, located in Bratsk, Russia).