The most powerful person in the global economy? That’ll be your US Federal Reserve chair. With their every utterance, the agenda-setter for US monetary policy and banking regulation moves financial markets and sends central bankers in smaller economies scrambling.

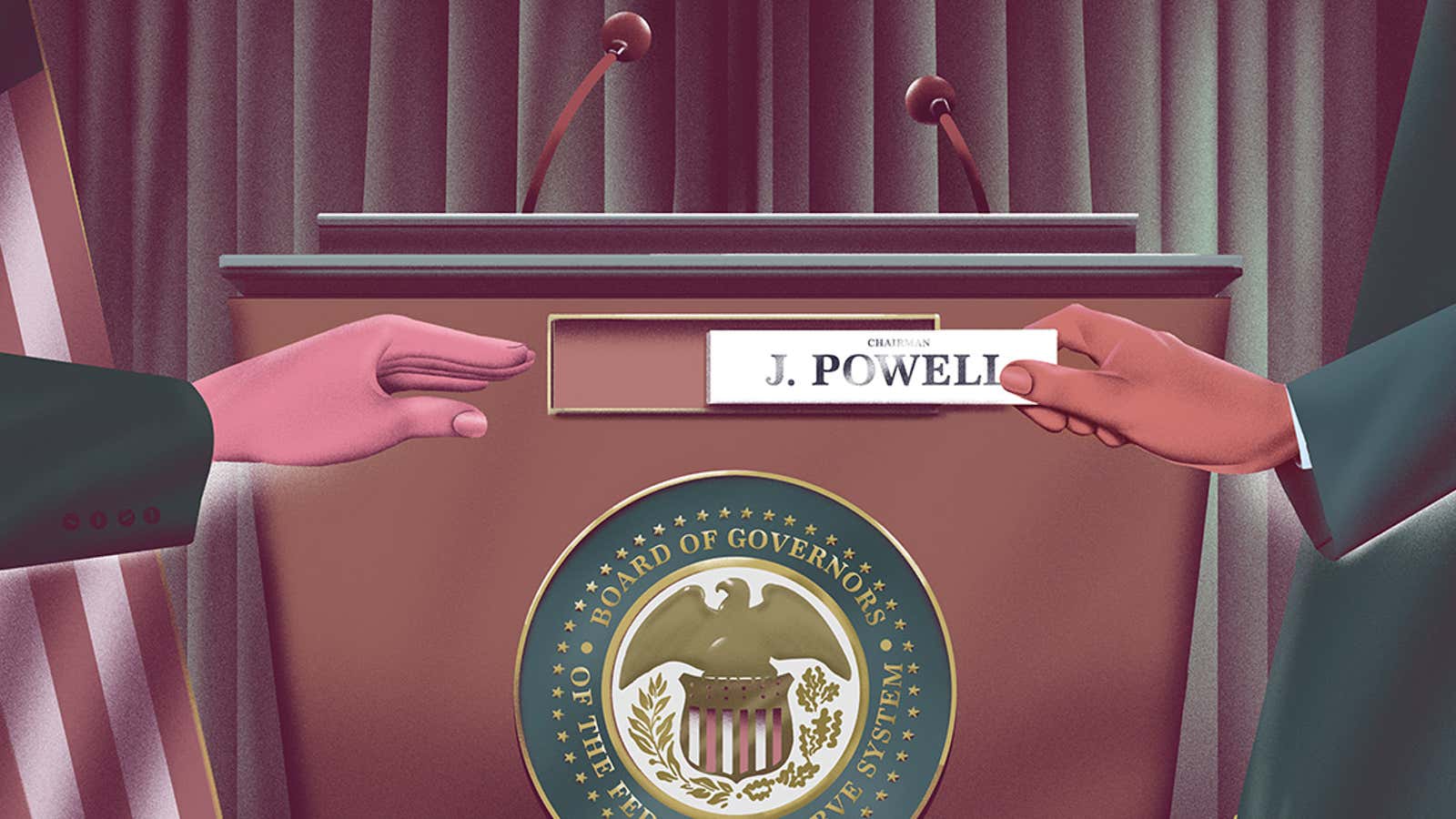

Right now, Jay Powell is in the hot seat. The Republican lawyer, chosen for the job by president Donald Trump in 2018, has won plaudits for embracing a decidedly dovish approach to managing the economy. With his term as chair expiring in early 2022, president Joe Biden now faces the decision of whether to reappoint him for a second term or tap a new person for the all-important role, with an announcement expected sometime this fall.

The decision comes as the world emerges from the pandemic with its supply chains snarled, which is raising prices and concern about inflation even as joblessness remains elevated. The Fed chair will have to navigate this complex transition while looking ahead to future crises. This is what the White House team will consider as it makes one of the most consequential choices in Biden’s first term.

WHAT’S UP, FED?

In recent years, central banks of the world have focused on inflation. It has been so well controlled that, despite this burst of pandemic-inspired price increases, Powell has suggested his bigger worry is disinflation.

And that’s a sea change: The recovery from the Great Recession, which saw unemployment fall to 3.5% while inflation remained quiescent, upended the idea that high levels of employment conflict with price stability. In Powell, economic thinkers who care about full employment and inequality have found an unexpected champion. Though he was appointed by a Republican and has won the endorsement of some GOP lawmakers, many conservatives don’t prefer Powell’s approach and would like a chair focused squarely on inflation. Luckily for the American workers, those voices aren’t at the table where his successor will be chosen.

But if liberals are the winners of the traditional macroeconomic policy battle and happy to renominate Powell, there are other demands on Biden from the left. Powell has rolled back some of the restrictions on the financial sector put in place after the 2008 financial crisis, worrying observers who cast banks as the central villains in the economy. And other voices are demanding the Fed stretch its mandate to include fighting climate change, one of the central threats to prosperity in our times.

FOR/AGAINST

The case to keep Powell is that a dovish Fed chair doesn’t come along every day.

- Biden can be confident that Powell will support a growth-friendly economy, which has to be a key consideration going into important elections in 2022.

- Another political concern: It’s hard to imagine a more explicitly progressive pick making it through Senate confirmation, where conservative Democrats cast the deciding votes.

- From a markets perspective, keeping Powell is likely to offer some sense of stability to investors.

- If Powell is too soft on banks, there are other upcoming vacancies on the Fed board to which Biden can nominate someone with a more stern supervisory bent.

- On climate, Powell advocates believe a robust and worker-friendly economy will do more to promote decarbonization than trying to use financial regulation to fight emissions.

The case to boot Powell is that Biden can force through a more transformative figure or increase representation by appointing a woman or person of color.

- Powell was too slow to recognize the threat of climate change. More environmentally-inclined candidates include Fed board member Lael Brainard (though she doesn’t diverge too far from Powell) and former Bank of England chair Mark Carney (though it’s hard to imagine the Senate confirming a foreigner, whatever the wisdom of the idea).

- These chairs are more likely to limit risk-taking in the financial sector by requiring banks to hold more capital and limit leverage.

- And though neither figure embraces radical ideas like blocking financing for fossil-fuel companies, they might be more eager to raise the cost of financing for carbon-intensive industries through financial regulation.

- The central argument might simply be opportunity cost: If Biden sticks with Powell, the next new chair isn’t likely to be appointed until 2026.

How should the Fed fight climate change?

What’s new in the fight over Powell compared to prior Fed chairs is the idea that central banks need to do more to fight climate change. Extreme weather, changing agricultural conditions, and other impacts of global warming could cost an estimated 11-14% of global GDP by 2050, according to the insurance giant Swiss Re. That’s a threat that central banks need to prepare for. The question is, how?

One answer, favored by progressives like rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, is to use the Fed’s regulatory toolkit. When it performs “stress tests” on large banks, the Fed could incorporate climate risk, an idea that the bank is considering. It could also take more radical steps to force large banks to hold more capital for loans to fossil-fuel companies or charge them higher interest rates. Or, when the bank uses purchases of financial assets to support the economy, it shouldn’t buy bonds that finance carbon-intensive industry. These measures could make it more difficult for fossil-fuel companies to operate—or it could drive the financing of those businesses outside the formal banking system, to private equity and other less regulated funds.

Progressive economists concerned about climate change worry this is using the wrong tool for the job. Decarbonizing the economy won’t be cheap: It will require all kinds of investment, and it’s more important for the Fed to support an environment conducive to public spending on green infrastructure. Supporting Powell’s approach to monetary policy, in this view, is more important than the Fed slow-walking bank regulation. It’s also worth noting that financial regulation doesn’t have a great record of changing real economic activity: Attempts to use SEC disclosure rules to stop the use of conflict diamonds haven’t seen great success. The Fed’s tools are fairly blunt, and they haven’t been used to alter the economy this way before.

🔮 Prediction

Most Fed-watchers predict that Biden will renominate Powell. With a reported endorsement from his Treasury secretary Janet Yellen, a former Fed chair herself, it will burnish the president’s bipartisan credentials, avoid a costly political fight, and allow the self-described “jobs president” to have a Federal Reserve that takes full employment seriously.

Reading List

Powell received plaudits for his work doing the pandemic financial crisis. This New York profile offers a compelling portrait of the current chair.

The Fed’s “new framework” is a sea change in monetary policy. Here’s what that means.

Potential future Fed chair Lael Brainard delivered this speech explaining her views on climate change and financial stability in March 2021.

Central banks say “neutrality” prevents them from adopting green policies. Two economists argue this is the wrong view.

Here’s the opposite view. Against central bank “mission creep”.

This group evaluated the environmental impact of central banks. China comes out on top, but mainly because the People’s Bank isn’t independent of the country’s central government.

Trivia time

How long was the longest tenure of any Fed chair?

a) 7 years

b) 14 years

c) 18 years

Answer at the bottom.

In last week’s poll about dining out, 38% of respondents said they were sticking to outdoor dining for the time being. Now’s a good time to buy those fingerless gloves for dining al fresco in cool weather.

Have a great week,

—Tim Fernholz, senior reporter (and member of the central bank illuminati)

One 💰 thing

Running for president in 1999, the late senator John McCain was asked if he would re-appoint Fed Chair Alan Greenspan, then serving his third term. “I would not only reappoint Mr. Greenspan,” McCain said, “if Mr. Greenspan should happen to die, God forbid—I would do like was did in the movie ‘Weekend at Bernie’s.’ I’d prop him up and put a pair of dark glasses on him and keep him as long as we could.”

The answer to the quiz is c) 18 years. William McChesney Martin, appointed by president Harry Truman, held the role for a total of 18 years and 304 days between 1951 to 1970. Reagan-appointed Alan Greenspan is a close second, clocking his tenure at 18 years and 173 days between 1987 and 2006.