Hi Quartz members,

You might have seen it: They finally put a machine gun on top of one of those disconcerting robotic dogs. But it wasn’t a ‘bot built by Boston Dynamics, which pioneered automated platforms that can leap, run, and get back up when you kick them over. Boston Dynamics has said it won’t arm its robots. Instead, the gun-toting machine on display at a US Army expo this month was crafted by Ghost Robotics and Sword Defense, less well-known firms that promise the “future of unmanned weapon systems, and that future is now.”

Autonomous weapons are now seen by the military as the next evolution of warfare, even as some US tech workers object to working for organizations that might deploy artificial intelligence to kill or surveil. Many technologists read about drone strikes killing innocent civilians and see the US and other nations abusing surveillance powers in ways that don’t seem all too respectful of human rights. And they’ve seen the regrets of scientists who unleashed the age of atomic weaponry with little thought to its broader implications.

Make no mistake: the US tech sector still does lots of work for the military and that won’t change anytime soon. For every Boston Dynamics that won’t arm an AI, there will be a Ghost Robotics.

But, as a US government commission that included former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and current Amazon CEO Andy Jassy recently warned, Russia and China won’t hesitate to seek battlefield advantage, and the US will need the best possible tech to preserve democracy.

One way forward? Adopting principles that draw bright lines around robotic weapons could be the smartest path, for humanity and Silicon Valley alike.

A brief history

1675: The Strasbourg agreement limits the use of poisoned bullets; it is seen as one of the first arms control treaties

1958: Fairchild Semiconductor, a pioneering Silicon Valley firm, wins a contract to make chips for Minuteman nuclear missiles. The US government provided early investment in and demand for modern transistors

1968: The Treaty for the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons is signed

1969: The first message is sent between two computers connected to Arpanet, the Pentagon-funded networking experiment that would eventually become the internet

1983: Funded by the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), Israeli engineer Abraham Kerman builds an automated aerial vehicle in his garage that would become the basis of future US drones

2003: Palantir, the data analytics company, is founded with an explicit mission of fighting terrorism

2015: The Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) is formed to get advanced technology into the hands of the military more quickly

2017: China announces a $150 billion plan to become the world leader in AI

2018: Google ends its work with “Project Maven,” part of the Pentagon’s Algorithmic Warfare unit, after employees object

How are you enjoying our member-exclusive emails? We’d like your feedback in this short survey.

Term of Art: “Dual Use”

What makes some tech workers worry about AI? It’s a “dual-use” technology, which means it has civil applications—researching new drugs, driving cars, playing video games—and security uses—finding criminals, operating weapons platforms, tracking terrorists. And because the private sector can raise money and put new technology in the market faster than defense contractors, the best AI tech is (arguably) found at ostensibly “consumer-focused” companies, like Google.

It’s easy to see the unintended consequences of technology in events like the genocide in Mynamar, which was plotted on Facebook. During the Project Maven fracas at Google in 2018, some computer scientists resisted developing recognition tools that would be applied to video collected by autonomous drones. The Pentagon said the tech would be used to save time for human analysts hunting for terrorists, but technologists feared that it might be used to deploy lethal force, even without human supervision. This year, the Air Force will demo the use of the technology to select bombing targets.

Critics of the tech companies see their reluctance a different way: Google and other big firms don’t want to miss out on opportunities in China’s lucrative domestic market, and thus don’t want to be seen as tied to the American military.

The Military-Technical Complex

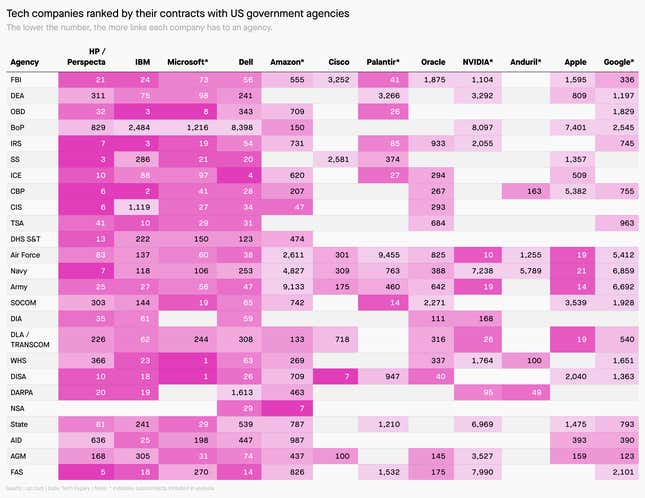

Despite Google’s decision to exit Project Maven, Silicon Valley writ large is doing lots of work on US national security, often through a web of sub-contractors. Jack Poulson, a Google computer scientist who resigned over the company’s work on AI, plumbed government records to demonstrate the deep links between the tech establishment and national security agencies:

Who will watch the robots?

The rise of companies like Palantir, Anduril, or even Ghost Robotics shows that even if major players leave behind the defense tech business, there will be firms eager to take on the challenge of protecting the US. But DOD officials still fret they are missing opportunities to draft the most talented engineers and scientists for AI projects because they don’t trust the military or intelligence services to operate ethically.

And then there’s the arms race issue. The development of advanced weaponry easily falls into a self-justifying dynamic of building more and deadlier weapons, and can lead to the misallocation of resources and economic problems. A hasty push to deploy AI in security work will increase the chances of mistakes due to bias, bad data, or plain old bugs.

Could a global agreement that limits AI weaponry or comes up with sound principles for its use help? Technologists and philosophers have called for such rules for more than a decade. International law is hazy on autonomous weapons, and even semi-autonomous applications, as with US drone warfare, exists in a gray area. The Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, an international agreement that limits the use of landmines and laser weapons, is discussing how to regulate AI, but progress has been slow at best.

One sticking point: Verifying that everyone who agrees to potential conditions on autonomous weapons sticks to the deal. AI development is even harder to track than nuclear weapons or intercontinental missiles, and as attempts to restrict nuclear non-proliferations show, inspections don’t satisfy everyone.

By the digits

13,000: Estimated number of civilians killed in US drone strikes in Iraq between 2014 and 2019

0.1%: Error rate for a leading facial recognition algorithm using high-quality mug shots, in a research setting

9.3%: Error rate for the same algorithm using imagery caught “in the wild”

20%: Chance the US uses an autonomous drone to kill a human in the next four years, per forecasters at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology

50%: Increase in federal contract money to the Big 5 US tech companies predicted by CSET forecasters

Prediction 🔮

Robot arms control will come too late. If there’s any lesson to be learned from past arms races, it’s that severe consequences precede efforts at restraint. International organizations struggle to define AI and its applications, and too many governments are paranoid about threats from abroad. It will take an accident, a trip to the brink of conflict—or a broader social movement to define the role of AI in human affairs. Responsible citizens and NGOs can only push for sound policies to be ready when the world comes to its senses.

Sound off

Are you comfortable with your government deploying robots that kill autonomously?

Yes, it’s the only way to protect national security.

No, it’s bound to backfire and cause an arms race.

Maybe, if there was some credible regime for governing their use.

In last week’s poll about decentralized finance, 32% of you said no thanks, you’d need more convincing to give DeFi a try, while 30% of you said you already have.

Keep learning

- “New Laws of Robotics: Defending Human Expertise in the Age of AI” (Frank Pasquale)

- Reports of a Silicon Valley/Military Divide Have Been Greatly Exaggerated (Tech Inquiry)

- National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence 2021 Final Report (pdf, the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence)

- Guidelines for human control of weapons systems (pdf, The International Committee on Robot Arms Control)

Keep your friends close, and your robots closer,

—Tim Fernholz, senior reporter (would rather not become death, destroyer of worlds)

One 🧨 thing

What was the first automated weapon? Arguably, land mines, which explode when a passerby triggers them. These weapons remain in place after conflicts end and present a terrible threat to civilians, who are the main casualties of these arms. Most of the world has banned these weapons, but the US expanded their use under president Donald Trump.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled the name of Amazon’s CEO. It is Andy Jassy, not Jolly.