Hi Quartz members,

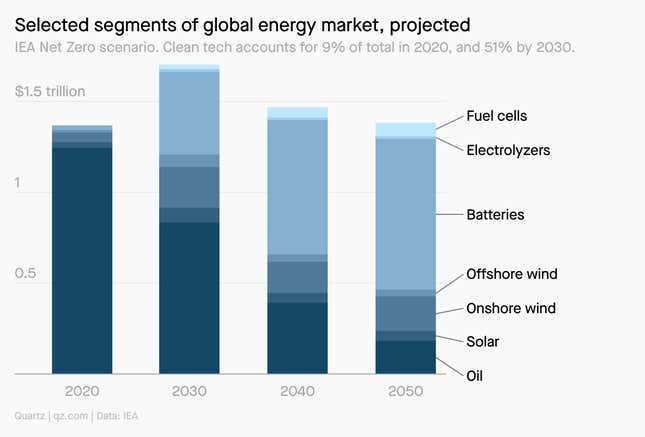

For nearly two centuries, the global economy has run on fossil fuels: Coal, oil, and natural gas. To avert catastrophic climate change, it needs to rapidly shift to new energy sources that emit little or no greenhouse gases. Solar and wind are great, but they can’t do the job alone. The economy needs not just cleaner electricity, but a lot more of it. As capital pours into climate tech and major energy companies look to decarbonize, some of the cutting-edge clean energy technologies that have been “just around the corner” for decades may now actually be within reach—and poised to generate huge profits. Let’s separate the hope from the hype.

💨 Green hydrogen

Hydrogen gas can be converted into electricity in a fuel cell, emitting nothing but water vapor. Because it packs a high dose of power into a small package, hydrogen could be an invaluable replacement for fossil fuels in industrial operations like steel and fertilizer production, and could power cars and other vehicles. But producing hydrogen gas in the first place requires electricity. The gas can be manufactured by pulling hydrogen atoms out of water; when the electricity to do that comes from renewable energy sources, the hydrogen is known as “green.” Green hydrogen can also act as a battery, allowing excess wind and solar to be converted into a tangible product tradable on the global market—potentially setting up sun-rich countries like Egypt and Saudi Arabia as future hydrogen export kingpins.

The UN projects that by 2050, green hydrogen could supply up to 20% of total global energy. But today, 99% of hydrogen is “blue,” made using natural gas or other fossil fuels—a process that is ultimately more carbon-intensive than burning those fuels directly. The trouble is green hydrogen is currently up to five times more expensive to produce than blue. Still, energy companies, particularly utilities and oil and gas producers, are plowing tens of billions of dollars into hundreds of green hydrogen projects around the world. And demand is growing: In June, for example, Volvo inked a major deal to source steel from an experimental factory run on green hydrogen. Wood Mackenzie, an energy consultancy, projects the cost of green hydrogen could fall 30% by 2030—and will be especially competitive with blue hydrogen once more countries impose taxes on carbon emissions.

⚛️ Nuclear fusion

The idea of virtually unlimited energy that produces essentially no waste or pollution sounds like a fantasy, and in the last few decades nuclear fusion has gone from humanity’s great hope to a punchline, perennially just out of scientists’ reach. But a genuine breakthrough in August at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, and the mounting urgency of the climate crisis, are fueling a new surge of optimism and investment.

Whereas traditional nuclear power entails splitting atoms, fusion is about conjoining them. It’s a mind-bending technological challenge that involves heating gases to temperatures hotter than the center of the sun and holding the resulting plasma in place with superpowered magnets or lasers. One key hurdle is to make this process work efficiently enough that it doesn’t consume more power than it produces. The Lawrence Livermore project set a record for energy production on Aug. 8—but the blast lasted less than a second.

None of this is cheap: One of the world’s most advanced projects, a 100-foot-wide machine being built in France, will cost $25 billion to complete. At least 35 startups are actively pursuing fusion and have raised at least $2 billion in private capital, including from the likes of Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates. Advances in 3D printing, artificial intelligence, and other ancillary technologies necessary for successful fusion are also charging ahead. But it’s not clear that investors and governments are yet willing to make the jump from laboratory R&D to full-scale commercial projects that could cost untold billions with no guarantee of success.

🔋 Next-generation batteries

Most electricity is generated in power plants shortly before it’s used. But the proliferation of renewable energy sources that can’t be timed to match demand, plus the rise of electric vehicles, means the world needs better, bigger batteries. The International Energy Agency projects that demand for energy storage could grow to 10,000 gigawatt-hours annually by 2040, up from just 200 today—a market that could be worth $278 billion by 2027 and overtake the value of the oil market by 2040.

Although their prices have plummeted precipitously in recent years—90% since 2010, for those used in EVs—batteries remain expensive. Today a typical EV battery runs around $6,300. And unfortunately, the minerals that allow them to pack a bigger power punch, especially lithium and cobalt, are both their most costly component and sometimes linked to human rights abuses. The race is on to find better, cheaper alternatives; the IEA reports that the number of electricity storage patents has seen an annual growth rate of 14% since 2005, compared to 3.5% on average economy-wide. Hot new materials like sodium and iron could be the missing piece that finally makes EVs affordable for everyone.

🌽 Advanced biofuels

Ideally, liquid fuel made from plants should be carbon-neutral, since the plants draw in CO2 while they grow and then release it when burned. Biofuels also have the advantage that they can be easily swapped for fossil fuels in many engine designs, especially for ships and airplanes that are hard to run on electricity. By 2050, the IEA projects, total biofuel demand could more than double, and power 40% of aircraft.

But today, most biofuels are more expensive than oil and, if made from plants grown on deforested land, could actually be worse for the climate. With the right land use practices, and the right plant species, it’s possible to produce biofuels with a net climate benefit. But it’s not clear that supply can be great enough to make a serious dent in demand.

🔮 Prediction

Costs will fall quicker than many people expect. Historically, energy market experts have been much too conservative when predicting cost declines for clean energy technologies. Only a decade ago, solar and wind were among the most expensive ways to generate electricity; now, in most parts of the world, they’re the cheapest. Supply chain constraints could put a price floor on some technologies—lithium batteries, for example—but the spread of carbon emissions pricing and future price spikes in the fossil fuel market will make clean alternatives increasingly competitive either way.

Sound off

Which nascent energy source will the economy rely on most in the future?

Something that hasn’t been invented yet

In last week’s poll about killer robots, 61% of you said that governments deploying autonomous killer robots is bound to backfire and cause an arms race.

Have a great COP26,

—Tim McDonnell, climate and energy reporter (reporting from Glasgow)

One 📈 thing

Hydrogen stocks heat up. After years in the doldrums, stock prices for green hydrogen companies are showing signs of life. Shares of Plug Power, a New York-based fuel cell producer, doubled in value between Oct. 2020 and Oct. 2021. Bloom Energy, a California fuel cell company, saw a similar bump. Morgan Stanley recently upgraded its valuation outlook for these and other hydrogen companies, and Bank of America named Siemens Energy and Air Liquide, both emerging as green hydrogen production giants, as “stock picks for COP26.”

To follow all the action from the major climate summit happening in Glasgow during the first two weeks of November, sign up for our Need to Know: COP26 newsletter.

Correction: Last week’s Forecast misspelled the name of Amazon’s CEO. It is Andy Jassy, not Jolly.