Hi Quartz members,

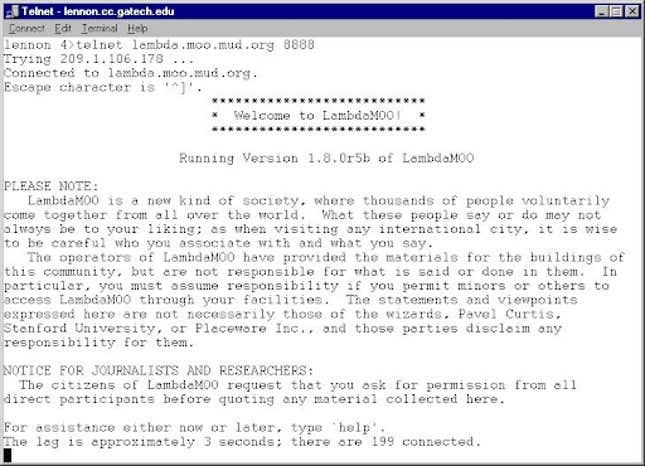

Early internet communities in the 1990s like Usenet, LambdaMOO, LiveJournal, and MySpace defaulted to screen names that could have as much or as little to do with a person’s real name as they wanted. But in the early 2010s, the dominance of Facebook and Google ushered in the real name web—where it became much more common to post real names and personal information online.

Today, some users, from crypto bros to privacy activists, are advocating for a return to the pseudonymous web—even beyond social media, and into our careers.

The internet, 1990s to 2010s

Pseudonyms flourished in the early days of the web because there was no expectation that you reveal anything personal online (beyond academics, who had institutional emails).

As a result, people were able to explore their identities and fantasies in chat rooms and other shared online spaces (IRCs, MUDs, and MOOs) while connecting with people across the world. Not everything was perfect, however. Cultural knowledge was easily lost, information was harder to sift through without curation algorithms or verifiable entities, and the web felt much more disjointed and clunky compared to the integrated systems we have today (like using your Google login across several sites), Oxford research fellow Bernie Hogan told Quartz.

Call me by my (screen) name

Then came Facebook, which opened to the public in the late 2000s. Because it launched as a way to connect people to their in-person college classmates, real name policies made sense as a way to scale it beyond requiring Ivy League email addresses. Some saw using real names online as a way to deter the increasingly big problem of bad behavior: South Korea introduced a real name law in 2007 after a cyberbullying-related suicide and national political slander against the government.

This issue ballooned during the nym wars of the early 2010s, when sites like Facebook and Google Plus cracked down on people using pseudonyms to enforce its culture of real world connections and inhibit online harassment. In an interview published in the 2010 book The Facebook Effect, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said:

“You have one identity. The days of you having a different image for your work friends or co-workers and for the other people you know are probably coming to an end pretty quickly… Having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity.”

But this equation started to change. Real name policies weren’t stopping harassment, while user privacy/anonymity were taking on renewed importance to the public. For example, South Korea’s real name law was struck down in 2012, after it was revealed to be ineffective and led to 35 million social media users’ personal information being stolen.

The status quo

Today, it’s clear real name policies are not a fix-all—in fact, Jillian York, the director for international freedom of expression at the nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation, describes them as the “white man’s gambit,” as white men are often the ones who propose real name policies, but don’t realize how these policies might hurt marginalized people. Starting in the mid 2010s, platforms like Facebook and Google began to roll back real name requirements.

“Americans, especially, tend to forget that, just because they’re free to talk about their proclivities or whatever subculture they’re a part of, most of the world is still not,” York says. “With increased surveillance across the web, I think that it’s really, really important that people are able to protect their identities and to use pseudonyms online to be able to explore who they are.”

Today, we’ve become adept at moving across alts, finstas, and identities from platform to platform—sometimes, even within platforms—to explore aspects of our identity and protect our privacy. From entertainment (Virtual Youtubers and influencers) to publishing (writers and scientists) to activism (Hong Kong protestors) to social networks, many already operate pseudonymously. The question is, what will it take for pseudonyms to be the norm again?

Quotable

“There’s this really strange push-pull in society where people are increasingly uncomfortable with policing offline, but they’re increasingly pushing for policing online. And I don’t really understand this dichotomy… If we’re trying to reform or abolish the police offline, why are we trying to turn corporations into the police online?” — Jillian York

A cypherpunk future in the making?

For pseudonyms to catch on, platforms have to grapple with the question of persistence: “It’s the persistence of a pseudonym that creates relationships and accountability and more prosocial behavior,” Jeremy Birnholtz, a communication studies professor at Northwestern University, says. (Disclaimer: Birnholtz was my professor at Northwestern).

Some Discord servers have leveling bots to indicate how active a community member is. But different tacks are needed when identity verification is more important; dating apps, for example, have experimented with ways to disincentivize catfishing via photo checks without requiring names.

On the individual level, how costly—and how normatively acceptable—will it be to start over, to be pseudonymous? “Not having a carrd is a red flag” / “dni [do not interact] if you don’t have a carrd in bio” is common Twitter discourse in certain fandom spaces, where some are shunned as suspicious for being pseudonymous/anonymous. (Carrds are one-page websites where teens often reveal anything from age, race, interests, sexuality, triggers, to mental illnesses.)

Currently, it’s hard to imagine the web becoming fully pseudonymous, as social networks have become the predominant way of maintaining real life relationships. But the capacity for pseudonymity should be protected, rather than eschewed.

So what are the new battlefields for pseudonymity online? Here are what a few experts envision.

Crypto, NFTs, and the decentralized web

In crypto, the idea of a more pseudonymous internet has gained traction as a part of the shift toward the decentralized, interoperable web (aka Web3). Several bitcoin developers, for example, work under pseudonyms to avoid scrutiny, maintain privacy, or detach their new projects from their established reputation, CoinDesk reported. DeFi project SushiSwap launched with a largely pseudonymous team.

Hogan argues that the rise of NFTs is helpful in thinking about this transition. NFTs allow us “to create authenticable identities that are cross platform that don’t need to be tethered to your real name identification credentials,” Hogan says. “They don’t need to be tethered to your birth date, your postcode, and gender, just for someone else to know that this is actually a person, a real person, and what they do.”

The metaverse

While the metaverse remains largely vague and undefined, the concept as well as the companies working toward it are redefining what it means to be online.

“Even if we take away the Facebook Metaverse, we are seeing a push towards VR and AR, and spaces where presumably you are going to be a representation of your offline self,” York says. “I don’t know what those spaces will require in terms of identity, but it worries me.”

Beefing up privacy tech

Current pseudonymity doesn’t guarantee anonymity. Birnholtz raises the question: Pseudonymous or identifiable to whom? People leave identifiable records behind that ISPs, platforms, or banks can still trace, so the pseudonymous aspect largely applies to other users of that platform.

Amid a big tech backlash, users could begin erring on the more extreme side of privacy, it could mean using privacy-oriented, decentralized tools: Tor browsers to block trackers, DuckDuckGo rather than Google search, multiple email addresses, crypto wallets, and a multitude of screen names.

Keep learning

- A More Pseudonymous Internet (The Atlantic)

- A Case for Pseudonyms (Electronic Frontier Foundation)

- Can Fake Accounts Save the Internet? (The New York Times)

- Pseudonyms and the Rise of the Real-Name Web (Bernie Hogan)

- Is it weird to still be a virgin? Anonymous, locally targeted questions on facebook confession boards (Jeremy Birnholtz)

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Online Anonymity (Anonymous Planet)

Sound off

What sites would you use a pseudonym on?

Everything, from email to work identity to social media

In last week’s poll about asynchronous work, 34% of you said you wish more than half of your work was done asynchronously.

Have a great week,

—Jasmine Teng, associate membership editor, (trying to avoid the mortifying ordeal of being known)

ONE 😮 THING

One interesting case is when pseudonymous networks pop up within platforms that have largely enforced real name policies. Before smartphones and Grindr became common in India, gay people constructed fake Facebook profiles with a variant of their real name to interact pseudonymously with a network of known people—albeit isolated from the rest of Facebook, according to Birnholtz.

“Facebook’s just a generic infrastructure for connecting people,” Birnholtz says. “… There are cases of pseudonymous networks that are isolated within today’s platforms, but they’re rare.”