Hi Quartz members,

People are having fewer babies than ever before. The global fertility rate is half of what it was at its peak in the 1960s. South Korea forecasts that its fertility rate, which already was the world’s lowest, will plunge to just 0.7 by 2024—meaning that each woman is expected to have fewer than one child on average. The precipitous drop in fertility means countries are facing aging populations and shrinking workforces, placing greater strain on social safety programs and government budgets.

Why are people having fewer babies? There are a few reasons:

- More women are waiting longer to have children as they delay marriage and prioritize their education and career

- Contraception (pdf) is becoming more accessible across the globe

- The cost of raising children has skyrocketed, making it unaffordable for those in countries with scant public support (pdf)

- Climate despair is leading some to rethink having children (though it won’t necessarily halt climate change)

- Infertility affects about 12% to 15% of couples

Governments (pdf) are trying to encourage baby-making by implementing improved parental leave, free child care, or child benefits payments. In the private sector, companies like Facebook, Google, and Apple have begun offering fertility services such as egg freezing as workplace perks intended to attract and retain employees.

Now, pioneering research is moving past traditional biological barriers to having children, making it more accessible to more people (as long as they can afford it).

THE STATE OF REPRODUCTIVE TECH

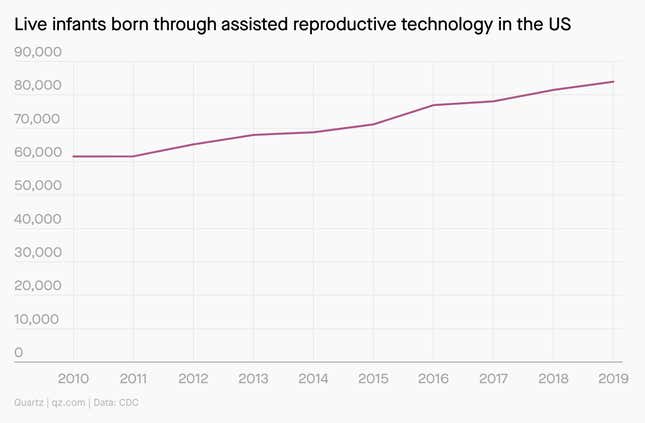

Using technology to have children has never been more common. In the US in 2019, nearly 84,000 infants were born through assisted reproductive technology (ART), up 36% from 61,556 in 2010.

Among the different ART procedures, in vitro fertilization is the most common. It’s been around for decades—the first “test tube baby” was conceived in 1978—but the procedure still costs anywhere from $12,000 to $20,000 on average for one treatment.

Over the past decade or so, however, live births from IVFs have declined. Norbert Gleicher, founder and medical director at the Center for Human Reproduction, blames the expensive but ineffective IVF add-ons that fertility clinics peddle to unsuspecting consumers, some of which may cause healthy embryos to be discarded.

Not all agree. Many women undergoing IVF are older, which will inherently decrease live birth rates, said Linda Sung, the director of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at NYU Langone Long Island. Also, in recent years, countries like the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have begun limiting the number of embryos in IVF transfers, which would decrease the birth rate.

Though also a 40-year old technology, egg freezing only became widely accepted in the last decade, after the American Society of Reproductive Medicine lifted the “experimental” label from medical egg freezing. A growing number of startups are marketing the procedure as a form of insurance for those that want to delay parenthood, but data on success rates is also scarce for such a pricey process. The egg freezing process alone can cost between $5,000 to $10,000 per cycle, not including additional fees stemming from fertility medication, yearly storage, or embryo creation.

UP NEXT: GENE EDITING

Researchers have tested embryos for genetic abnormalities since the 1990s. The practice, while initially unpopular, is widely used today.

But soon, newer procedures could do more than test embryos—they could correct the genetic underpinnings of harmful medical conditions. In 2016, the first baby was born in Mexico via mitochondrial replacement therapy, an experimental method for preventing the transmission of rare mitochondrial diseases by swapping in healthy DNA from another person. And in 2015, Chinese researcher He Jiankui claimed he was the first to create genetically edited babies using Crispr to eliminate a mutation that could cause HIV (his claims were never verified). Neither practice is currently widespread; mitochondrial replacement therapy is banned in the US, and, amid mass censure, He was sentenced to three years in jail for his work on Crispr-modified children.

As editing our genetic blueprint becomes more plausible, scientists and bioethicists are starting to consider the ethics that should govern how these procedures are done and who gets them.

Arguments against gene editing

Arguments against gene editing frequently call on the tale of Frankenstein or the idea of playing God. It’s hubris—just because we can, doesn’t mean we should. Safety concerns have also cropped up: What if gene fixes now cause unexpected problems down the line, when it’s too late?

Disability rights activists also say that gene editing promotes ableism. In embryonic screening and, in the future, with gene editing, parents are inherently selecting for “desirable” traits, implying greater worth to one over another. Some call it an extension of eugenics.

Furthermore, questions of access remain. Like IVF, egg freezing, and many other fertility services, gene editing would reinforce inequality because it’ll be a luxury only available to privileged, wealthy, and mostly white people. Marginalized people, including women of color, poor people, or people in the global south are already discouraged from having children because they’re deemed unfit parents, said Shui-Yin Sharon Yam, associate professor of rhetoric at the University of Kentucky.

“Even if there are positive aspects to human genetic engineering, due to the ableist and racist nature of healthcare, Black people, people of color and people with disabilities will not reap the benefits, if there are any. Instead, they’ll be more likely to suffer from the negative effects, including increased discrimination, that are sure to come from this,” Anita Cameron, disability rights activist, wrote in a blog post.

“The challenge marginalized folks face in reproduction is not necessarily infertility or sexual orientation, but systemic discrimination that sometimes takes the form of forced or coerced sterilization, and the lack of support in child rearing,” Yam told Quartz. “None of these problems will or can be solved by the development of new reproductive technologies.”

Arguments in favor of gene editing

Some argue the fear of designer babies is overblown because of scientists’ insufficient knowledge of genetics. Tweaking for eye color or hair color is relatively harmless—but editing for smarter, stronger babies isn’t really within the realm of possibility right now.

“I don’t think we’re going to have the ability to do that for decades, if ever,” said Hank Greely, a Stanford law professor who specializes in bioethics. “I think that’s a great science fiction trope, but it’s going to stay science fiction for quite a while, and maybe forever.”

The primary ethical issue should be around safety, instead of whether editing heritable genes is inherently good or bad, he said.

QUOTABLE

“Repro[ductive] tech will not solve any existing structural marginalization along racial, gender, and class lines. Hence, even when tech evolves, we must continue to grasp questions on accessibility, and whether and how the tech is being used to promote the ideal citizen subject: namely, a white, able-bodied, attractive person in the Global North. I think it all boils down to two questions: Who is it benefitting from the development of new repro tech? Who remains left out, or becomes exploited or further marginalized because of the new tech?” — Shui-Yin Sharon Yam, associate professor of rhetoric at the University of Kentucky

🔮 PREDICTION

In the next decade: Lab-grown babies

Soon, scientists will be able to create eggs and sperm from stem cells collected from people’s skin or other organs. The procedure, known as in vitro gametogenesis (IVG), would allow infertile people, same-sex couples, singles, or even polycules to have biologically related children.

Research is already underway. Japanese scientists Katsuhiko Hayashi and Mitinori Saitou have been at the forefront of IVG research: In 2012, they became the first to convert mice skin cells into sperm and immature egg cells (oocytes), which they were able to use to breed mice—but the process still required fresh ovarian tissues taken from mouse fetuses.

Scientists haven’t yet achieved this with human cells, though startups like Conception, Ivy Natal, and Gameto are working on developing the tech. The proof of concept may very well come in the next few years, but there will likely be at least a decade of safety testing.

Several decades away: Artificial wombs

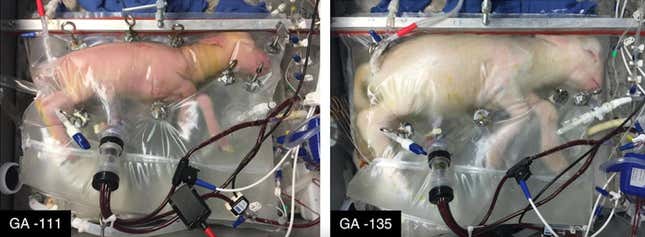

In 2017, a team of scientists developed an artificial womb—which they called the Biobag—that was able to support lamb fetuses outside of their mother. Their experiment wasn’t to test whether a fetus could fully develop in the artificial womb; it demonstrated the possibility of supporting babies born prematurely.

The biobag extended the viability of premature lamb babies—something similar could someday do the same for human babies. But actually growing an organism from blastocyst to baby is much more difficult. One big reason: the placenta. It’s a complex organ that is responsible for hormones, biosynthesis, and fetus monitoring that is difficult to replicate, said Linda Sung, the director of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at NYU Langone Long Island. Scientists have yet to replicate even a kidney, liver, or heart properly—and those are much simpler organs.

In the future, Greely imagines, we’ll eventually be able to grow a uterus from stem cells. But in order to produce a fetus, we’ll have to hook the uterus up to a heart-lung machine, and ensure that it’s being fed the right amount of hormones, properly oxygenated blood, glucose, and all of the other nutrients that a placenta provides.

KEEP LEARNING

- The business of fertility (Quartz)

- The End of Sex and the Future of Human Reproduction by Henry T. Greely

- How Silicon Valley hatched a plan to turn blood into human eggs (MIT Technology Review)

- The Last Children of Down Syndrome (The Atlantic)

- Egg freezing: Put it on ice (Quartz)

SOUND OFF

Which procedure do you find most fascinating?

Growing babies from stem cells

In last week’s poll about living on Airbnb, 65% of you said you’d consider becoming a digital nomad for a few months a year.

Have a great week,

—Jasmine Teng, associate membership editor (still hasn’t watched Gattaca)

ONE 🤯 THING

Male pregnancy is, theoretically, medically possible. Gender reassignment surgery allows doctors to create neovaginas, and further uterus or utero-vaginal transplants could support pregnancy. There have been no human trials to date. However, Chinese researchers impregnated male rats by sewing them to female rats last year, though there is limited application for human research.

But it probably won’t happen for a while: Uterus transplants to biological women are still extremely rare procedures. Roughly 70 transplants have been carried out to date, with 23 live births confirmed.