Hi Quartz members,

On Feb. 28, four days after Russia invaded Ukraine, president Vladimir Putin put his country’s nuclear forces on high alert. It was the first time since the country’s formation in 1991 that such an alert had been issued. Then, on March 24, North Korea tested an intercontinental ballistic missile designed to carry a nuclear warhead.

Not since the 1980s had the specter of nuclear war been so real in popular consciousness.

But the world today is not the same as it was during the Cold War. “This is the first time since the 1980s that we’ve had to confront the real possibility of nuclear escalation in a conflict with Russia,” says Todd Sechser, professor of politics and public policy at the University of Virginia, and a senior fellow at the Miller Center of Public Affairs. “But back then, one side sometimes believed the other was preparing its strategic nuclear forces for an all-out attack. That is not the kind of crisis we face today.” Nuclear weapons are clearly still a threat, but how countries consider that threat has evolved—“tactical” or “strategic” nukes are now a possibility, and they could be used on a non-nuclear power.

Here’s what Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could mean for the future of nuclear armament and diplomacy.

Buildup

Nuclear bombs are an inherently paradoxical: They exist in order not to be used, says Mariana Budjeryn, an expert on nuclear weapons at the Harvard Kennedy School. Nuclear powers make plans and build up their arsenals to credibly show that, if another country attacks with nuclear weapons, they’ll retaliate in kind.

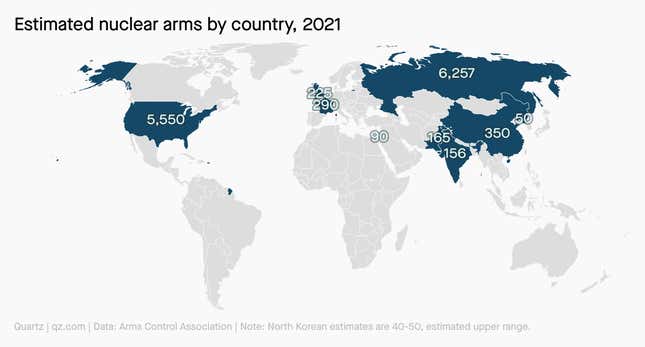

In 1945, the US dropped two nuclear bombs on Japan during World War II—the only nuclear weapons to ever be used in armed conflict to date. The US and the Soviet Union spent the Cold War building up their arsenals to prove to each other that their threat of retaliation was credible. Today, the US and Russia together have about 90% of the nukes on Earth.

In 1968, three of the five nuclear powers of that day—the US, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom—signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). (China and France did not.) The deal included an agreement to prevent countries that didn’t yet have nuclear bombs from developing them—and that (mostly) worked.

“Back in the 1960s, it was forecast that dozens more countries would acquire nuclear weapons, like 25 or 30. That hasn’t happened,” says Budjeryn. Today, in addition to the five nuclear powers at the time of the treaty, four more countries have nukes: Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea. “All together, nine—not perfect, but better than 30. The [non-proliferation] regime is credited with a lot of that.”

Another article in the treaty stated that existing nuclear powers would reduce their arsenal of nuclear weapons. That’s happening slowly; between 1994 and 2020, the US reduced its nuclear warhead stockpile by more than 11,000, while about 1,500 of Russia’s nuclear warheads are set to be dismantled.

But Russia also has a number of smaller bombs—so-called “strategic” nukes—that, if deployed on, say, a Ukrainian city, would be militarily and psychologically devastating, but might not be damaging enough to elicit a full-scale nuclear response from the US or its allies.

“Nuclear weapons are an old technology—invented before microchips, personal computers, pocket calculators, and even transistor radios. Yet they remain the ultimate weapon,” Sechser says. “The reason is simple: With nuclear weapons, countries do not need to win wars to inflict grievous harm on their enemies.”

Disarmament

In 1991, when the Soviet Union fell apart, the country’s weapons were divvied up between four former Soviet states: Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine. By the end of 1996, the latter three nations had agreed to turn their weapons over to Russia. They did so largely for pragmatic reasons—nuclear weapons are expensive to maintain, and giving them up came with security guarantees. Still, it took some convincing.

When Russia first invaded Ukraine in 2014, it violated those guarantees. Now there are some in Ukraine who regret getting rid of their nuclear weapons. “We gave away the capability for nothing,” Andriy Zahorodniuk, a former Ukrainian defense minister, told the New York Times in February.

Experts fear future disarmament efforts will be an even tougher sell. “Russia’s invasion will make it even more difficult to reassure countries that they can be safe without nuclear weapons,” Sechser says. On the other hand, says Budjeryn, “should Ukraine somehow prevail and restore its sovereignty, it will be a really good thing [for disarmament]. We can say, ‘This is a country that disarmed, they didn’t need nuclear weapons.’”

🔮 Prediction

Though most experts agree Putin is unlikely to use nuclear weapons, no one is willing to totally rule it out. Budjeryn thinks it’s more likely that he’d use a “strategic” nuke now that the war is calcifying into a stalemate than he might have at the start of the invasion. Last week, Putin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told CNN that Russia would consider nuclear weapons if faced with an “existential threat.”

It’s too early to fully know how the Russian invasion of Ukraine will change nuclear politics, but here are some of experts’ guesses about what could happen over the next decade.

Countries with nukes build up their arsenals again. Today, the New START Treaty between the US and Russia limits how many nuclear weapons each nation can have. That treaty expires in 2026; if relations between the US and Russia stay chilly and they choose not to renew, “for the first time since the 1960s, the world will be left with no treaty limiting the use of nuclear weapons,” Budjeryn says.

Countries without nukes might be more likely to develop a nuclear program. If Russia uses nukes on Ukraine, even “strategically,” other countries may feel having their own nuclear weapons is the only way to defend themselves against an attack from a nuclear power.

A shift away from nuclear energy. Nearly a quarter of Ukraine’s power comes from nuclear energy. As Ukrainian nuclear plants have become desirable targets in Russia’s invasion, some experts fear nuclear meltdown. Countries that have looked to nuclear power because it emits few greenhouse gases (although it comes with other problems such as waste) may reconsider after seeing Ukraine’s nuclear power plants become vectors for further risk during the conflict.

Sound off

Will some nation use a nuclear weapon in the next 50 years?

No, the threat of retaliation is still strong.

Yes, a smaller weapon against a country without nukes

Yes, we’re returning to the brinkmanship of the Cold War

No, nuclear arsenals will continue to shrink in size and relevance.

In last week’s poll about gaining points in your everyday life, 72% of respondents said they’d pass, that it sounds too dystopian. Okay, but you don’t get any points for that answer.

Keep your cool this week,

—Alex Ossola, membership editor (born when the Cold War ended)

One 🤯 thing

Sleeping just a little too well at night? This’ll fix that. Try out the nuke map, a project that estimates the impact of various nuclear detonations on maps of global cities. Since it was created in 2012, the site has rendered “255.8 million detonations and counting!” as it cheerfully proclaims.

Why would someone use such a morbid tool, you might wonder? “There are two categories of how people use Nukemap. The first is cathartic nuking, which is nuking somebody else. Say, Americans are mad at Russia, so they’re seeing what happens when you do it to somebody you don’t like. The second is experiential nuking, or nuking yourself to see what happens if it happens to me,” the site’s creator, Alex Wellerstein, told Charlie Warzel’s Galaxy Brain newsletter in an excellent Q&A. After playing with the site for a while I can confirm that it’s oddly fascinating.