Hi Quartz members,

The European Union is taking a hammer to American tech giants with new antitrust legislation.

In late March, it finalized the Digital Markets Act, a law that aims to break the stranglehold of large internet “gatekeepers” like Google, Meta, Apple, and Amazon. The law will, for example, require Apple to allow iPhone users to download apps from other app stores. And it will force WhatsApp and iMessenger to interoperate with other messaging apps.

The DMA is another instance of the EU leading the way in regulating Big Tech—its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was a landmark for data privacy rules and inspired copycat regulations in other countries.

And though US policymakers are nominally committed to reining in tech giants, not all of them are happy about the DMA. In December, US Commerce secretary Gina Raimondo expressed “serious concerns that these proposals will disproportionately impact US-based tech firms.”

Raimondo is right that the EU’s new law could put US tech at a disadvantage, but not because of the potential damage to Apple or Google. There’s growing recognition—even in Silicon Valley—that tech giants impede new companies from reaching their potential. In January, famed startup accelerator Y Combinator joined 34 other tech companies in support of antitrust legislation. The real risk for the US economy is that the EU becomes a better place to start certain types of tech companies because the DMA makes it easier to compete.

There was a time when European tech was dominated by copycats of American companies. Now, with its own antitrust efforts stalled in courts and in Congress, it’s the US that needs to catch up.

What’s in the DMA?

- Defining “gatekeepers”: The act covers companies of a certain scale and reach—those that have a market cap of more than €75 billion ($82 billion) or annual revenue of more than €7.5 billion. They must also provide services such as messaging or social networking to at least 45 million monthly users in the EU.

- Interoperability: The act will require certain services, such as WhatsApp, iMessage, and Facebook Messenger to become interoperable with smaller service providers over a period of four years.

- Privacy: The act prohibits companies from combining data from different subsidiaries that offer internet services.

- Self-preferential treatment: Restrictions on directing consumers to related services or products could impact Amazon or Apple’s App Store and Google Play.

- Penalties: The EU can fine a company up to 10% of its total worldwide revenue, or 20% for repeated violations.

🔮 Predictions

💬 iMessage competitors. Non-Apple users haven’t had easy access to iMessage features, but that may all change since the DMA requires messaging platforms to offer interoperability with other messaging tools. Some worry that this could threaten WhatsApp and iMessage’s end-to-end encryption, though.

💰More money for European tech. “The likely response will be that there are new startups and a lot more digital activity in Europe because those firms can get in and get access to consumers,” Fiona Scott Morton, an antitrust economist at Yale, told Quartz. “There’s going to be a big uptick in investment there.”

⚔️ More competition. New entrants will be able to break in with subscription-based models and incumbents will have to start thinking about their long-term innovation strategy, Nicolas Petit, professor of competition law at the European University Institute in Florence, told Reuters.

💾 EU-US tension over data flows. While the US and EU recently agreed on a framework that would make cross-border data transfers easier, the DMA could make American companies have to work even harder to move data.

🇺🇸 US antitrust regulation? The Senate Judiciary Committee passed the American Innovation and Choice Online Act in January, and the Department of Justice backed it in March. The bill would prohibit Meta, Google, Apple, and Amazon from giving preference to their own products.

One big question

How can messaging platforms become interoperable without breaking end-to-end encryption in services like iMessage or WhatsApp? Not all messaging platforms use the same kind of encryption, and cryptographers are concerned that companies will degrade the security of their cryptography in order to comply with the DMA.

“Changes of this complexity risk turning a competitive and innovative industry into SMS or email, which is not secure and full of spam,” Will Cathcart, Meta’s head of WhatsApp, said in a statement to Wired.

Companies might need to agree to a universal standard of encryption or develop APIs that connect to their messaging services. In a world of increasing surveillance, ensuring that encrypted messaging is secure is paramount, noted tech journalist Casey Newton. In a conversation with Newton, Cathcart also suggested that the ability to control messaging might affect WhatsApp’s ability to combat hate speech and misinformation.

Keep learning

- After China, the next big move against tech giants is coming from Europe (Quartz)

- Europe’s Digital Markets Act takes a hammer to Big Tech (Wired)

- EU’s faster, harder stick will whack US big tech (Reuters)

- US regulatory inaction opened the doors for the EU to step up (Brookings)

- Forcing WhatsApp and iMessage to work together is doomed to fail (Wired)

Sound off

The DMA…

- Won’t do much to dent big tech (nothing seems to)

- Will unleash a wave of European startups

- Will be a setback for encryption

- Will be followed by copycat laws around the world

Last week, 62% of you predicted a nuclear weapon will be used in the next 50 years. We sure hope you’re wrong.

Have a great week,

—Nate DiCamillo, economics reporter (is sometimes too competitive 😬)

—Walter Frick, executive editor, membership (gatekeeper of the Forecast email)

Additional contributions from Jane Li & Tripti Lahiri.

One ⚖️ thing

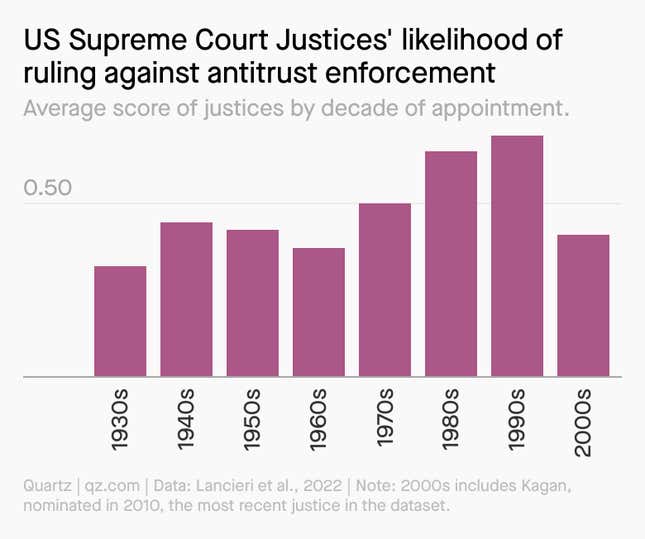

Since the 1980s, the US Supreme Court has grown consistently more pro-business and been less likely to enforce antitrust law.

That could change, as both the legal and economic understanding of monopoly adapts to the digital era and as cases against Meta and other tech giants work their way through the courts. But changing judges’ minds can take decades; writing new rules tends to be much faster.