Hi Quartz members,

Some call it “the policy that shall not be named.”

Given that ominous moniker, it’s perhaps surprising that industrial policy making is making a comeback in the US—and more broadly, the West. The term refers to a range of policies designed to actively spur technological development and promote key industries and, while it never fully went away, it became toxic in some circles at the height of free-market economics.

The US has a long history of industrial policy going back to the days of Alexander Hamilton. In more modern times, the government has used industrial policy across numerous sectors, with varying degrees of success. Government involvement has directly shaped key American industries—including Silicon Valley and biotech, and the oil and gas shale boom of the past two decades—through government R&D funding, public contracts, and tax credits.

But some economists soured on it, arguing that it wasn’t the government’s job to pick winners and losers, and warning of the risk of politicians pushing policies that enrich themselves.

Now, industrial policy is back thanks to the US-China strategic competition and the global energy transition (which now includes Europe’s urgent bid for energy independence).

“The comeback is inspired by China more than anything else—fear that the US is being overtaken in multiple high-tech industries, coupled with fear that China has discovered the magic sauce of industrial innovation,” says Gary Clyde Haubauer, non-resident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE).

Still, industrial policy needs a rethink to meet new geo-economic challenges, including the complexity of modern supply chains, China’s dominance in numerous critical industries, and fundamental shifts in global geopolitics.

What will the new era of industrial policy look like and how will it shape the global economy?

🤓 Explainer

What is industrial policy? Fundamentally, it’s any policy in which the government actively promotes production and development in sectors that it deems desirable for economic, geopolitical, or security reasons. It can include a number of economic policy tools, such as:

- Grants and loans: These provide firms with financial support to, for example, train workers, develop technology, and fund capital expenditures.

- Subsidies: Company-specific or industry-wide subsidies can be used to boost production and revenue—but can also cause massive inefficiencies. Over 3% of China’s output is devoted to direct and indirect subsidies.

- Long-term procurement: Purchase contracts from the government mean firms can reliably count on a big customer.

- Preferential tax policies: Tax credits and tax breaks can be used as incentives for whole industries. The US, for example, is considering tax credits for domestically produced rare earth magnets.

- Export controls: Governments might ban or limit the export of raw materials to protect domestic resources for national security reasons, and to promote more downstream processing and manufacturing.

- Import tariffs: These can be used to protect domestic industries from competition. And non-tariff policies can have a similar effect; one could argue that China’s Great Firewall shielded domestic startups from competition while allowing some foreign ideas to filter through.

Determining which tools to use, when, and at what scale, can make the difference between good industrial policy that advances technological development and a country’s competitiveness, and bad industrial policy that is both wasteful and market-distorting.

As Harvard economist Dani Rodrik put it in 2010: “The real question about industrial policy is not whether it should be practiced, but how.”

So what makes good industrial policy? PIIE’s Haufbauer says success is advancing the technological frontier, and doing so at a reasonable cost. He points to Operation Warp Speed, which saw the US government spend billions to fund the development of covid vaccine candidates, as one example.

Successful policies often focus on spurring research and development, Haubauer said. On the flip side, bad industrial policy includes opaque subsidies and high trade barriers.

But often, it’s hard to predict what will make good or bad industrial policy, says Myrto Kalouptsidi, assistant professor of economics at Harvard.

Her research into the Chinese shipbuilding industry illustrates this. The Chinese government started out by using broad subsidies to spur investment, production, and firm entry. After 2008, subsidies were much more targeted toward productive firms—and were more effective in raising output and revenue, says Kalouptsidi.

📈 Charted

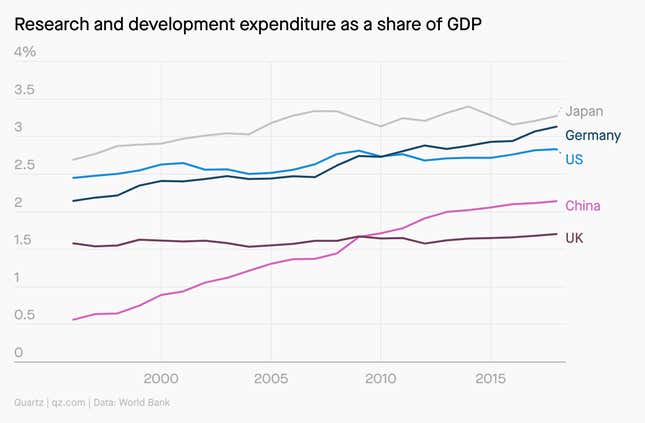

Public spending on research and development is a big part of industrial policy, as are incentives to promote private sector R&D. Though China has made big strides in recent years, its R&D expenditure (private and public combined) still lags behind that of the US, Germany, and Japan.

🔮 Predictions

Climate policy will require industrial policy: Alessio Terzi, an economist at the European Commission, thinks there will be a new era of “green industrial policy.” The energy transition is akin to a new industrial revolution, transforming modes of production, distribution, and consumption. “If…we look back at how industrial revolutions have played out in the past, we see how governments have been involved in these pivotal moments,” he says.

Industrial policy can help fix supply chain snarls: The pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war have upended supply chains worldwide. This could push governments to more actively encourage domestic production and sourcing. “If anything, the supply chain disruption may prolong the usage of [industrial policy] globally,” says Harvard’s Kalouptsidi.

The US will consider an industrial policy bank… The US could set up an industrial policy bank to provide cheap credit to promising firms, suggests Haufbauer. But the bank’s board must “have a high representation of retired Wall Street alumni with proven track records, rather than retired politicians” to avoid problems of projects being picked based on political calculations rather than commercial viability.

…And an industrial policy corps: Or perhaps we’ll see “a cadre of US tech diplomats,” who will implement international aspects of American industrial policies such as research agreements and infrastructure development, says Stephen Ezell (pdf) of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF).

Keep learning

- Scoring half a century of US industrial policy (PIIE)

- The Rise of China’s Industrial Policy, 1978 to 2020 by Barry Naughton (book)

- Boulevard of Broken Dreams by Josh Lerner (book)

- How China uses tax policies to defend its rare earths monopoly (Quartz)

- China has a stinging critique of the US’s supply chains strategy (Quartz)

📣 Sound off

Should governments use more industrial policies?

- Yes, governments need to set the economy’s direction

- Yes, but just funding R&D and writing the rules for companies

- No, it’s better left to the market

Last week, you were very divided over how to fix Twitter. ‘Become a protocol’ (31%) just barely beat a focus on creators (28%). We’ll let Elon know.

Have a great week,

—Mary Hui, reporter (fell into the industrial policy rabbit hole via rare earths)

One 🇨🇳 thing

Technology and knowledge transfers can drive economic growth. China has long used its industrial policy to convince or compel foreign companies to share technology and know-how with domestic firms. Overseas acquisitions can also be a way of acquiring advanced technology.

The US is catching on to this tactic. Last month, the executive director of a US battery manufacturing trade group called for the US to copy China’s playbook of exchanging market access for technology.