Hi Quartz members,

The US banned leaded gasoline nearly 40 years ago—for automobiles. But every day, small aircraft all around the country refuel with leaded gasoline, representing a 192-million-gallon-a-year loophole for the country’s 170,000 piston-engine airplanes.

Getting rid of lead was one of the 20th century’s greatest public health success stories. Concentrations of the neurotoxin in US children’s blood plummeted more than 96% from their highs during the 1970s, when an estimated 200,000 tons of lead was being spewed out of smelters, incinerators, and tailpipes each year.

But lead never really disappeared. In the US, it remained in water pipes, soil, old paint, and even refueling stations (you can still fill up off-road vehicles and boats with leaded gasoline today). Globally, more than 800 million children, about one in three, are still routinely exposed to elevated levels of lead.

The biggest source of airborne lead in the US today? That would be small aircraft, which emit 468 tons of it every year.

Most of this ends up drifting over communities within a kilometer of the country’s general aviation airports. Inside that radius, you’ll find more than 3 million children—and study after study has shown lead’s grave effects on the brain and nervous system, and consequences for children that cascade into their adult lives, from lower IQs to ADHD.

Lead emissions from aircraft present a public health threat on par with Flint, Michigan’s water crisis, say scientists like Sammy Zahran, an economist and public health researcher at Colorado State University. Unlike the water crisis in Flint, however, airport emissions go on every day, all year round, across the thousands of neighborhoods around the country that are home to a regional airport. Jets such as commercial aircraft burn an unleaded version of kerosene because they lack pistons; they don’t need lead which ensures even combustion in piston-driven engines.

Quartz just published a six-month investigation about how aviation fuel is poisoning a generation of Americans, and how—after decades of delays and resistance by oil companies, aircraft manufacturers, and even federal agencies—a solution may exist inside an airplane hangar in Ada, Oklahoma.

Join us as we look at what it would take to end the use of leaded aviation gasoline in the US.

The backstory

In 1923, the first gallon of leaded automobile gasoline was sold in the US. The additive, known as tetraethyl lead, was so toxic even a splash on the skin could be lethal. But it helped engines run better.

Within a few years, almost everyone alive was getting a hefty dose of lead from the air. Once inside the body, the tiny airborne lead particles penetrated deep into the lungs, crossing into the brain and bloodstream. Soft tissues and organs such as the liver, kidneys, lungs, brain, spleen, muscles, and heart soaked it up. The damage was extensive: Children suffered lower IQs, hyperactivity, impaired cognition, and behavioral issues, even at levels labeled “safe” at the time by public health officials.

By 1973, US regulators started phasing out lead from automobile gasoline, but left it in aviation fuel because some aircraft still needed the octane boost lead provides. What followed was decades of failed attempts, delays, and even obstruction by oil companies, aircraft manufacturers, and federal agencies.

The FAA now plans to approve an unleaded aviation fuel by 2030. But one community is refusing to wait that long. In January, Santa Clara County in California issued the nation’s first ban on leaded refueling at the Reid-Hillview Airport in San Jose, over opposition from pilots and the FAA.

A connection made

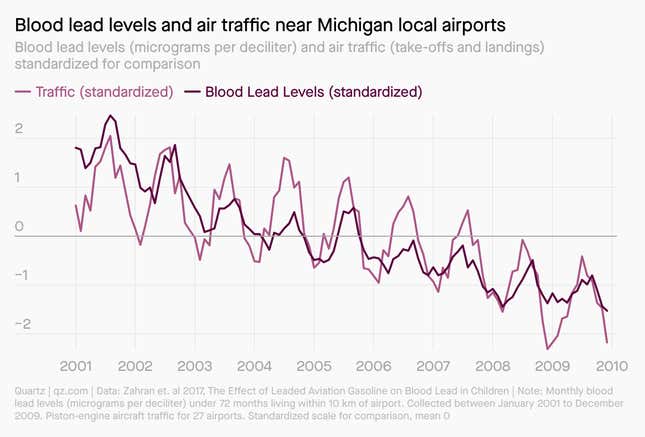

In 2011, Marie Lynn Miranda at Duke University uncovered a startling connection in North Carolina: Children’s lead levels rose the closer they lived to small airports. But it was hard to rule out other factors. So Zahran looked at lead levels in 1 million children in Michigan. He not only found higher lead levels near airports, but the amount of the heavy metal in children’s blood tracked the peaks and valleys of air traffic at nearby airports, often down to the month. It was the most convincing link between aviation gasoline, or avgas, and lead in children’s blood—a link reconfirmed in studies done around airports like Reid-Hillview.

The toll lead takes on health

Lead causes the body’s cellular mechanisms to go haywire. Cells repave themselves with the heavy metal. Proteins malfunction. Genetic instructions get garbled. Nerves’ electrical impulses, usually gliding along beds of calcium, are derailed by lead atoms. As millions of neural connections are severed, the mind begins to flicker less brightly and can even shrink, particularly brain regions controlling executive judgment, impulsivity, and mood.

Since 1990, more than 6,000 studies on lead’s health effects have come out, notes the EPA: All show “exposures to low levels of lead early in life have been linked to effects on IQ, learning, memory, and behavior,” damage that is permanent and untreatable.

Even blood lead levels as low as one microgram, equivalent to less than a thimble added to a large backyard swimming pool, double a child’s odds of developing ADHD, according to one 2006 study. “That’s the number that is currently keeping me up at night,” says Aaron Reuben, a PhD candidate in clinical psychology at Duke University. “This is what they mean when they say there is no safe level of lead.”

🔮 Predictions

George Braly, the co-founder of General Aviation Modifications Inc (GAMI), has been trying to replace leaded avgas for more than a decade. He’s on the verge of selling his first gallon of unleaded fuel, after years of resistance from oil companies, which stand to lose a profitable market for leaded avgas.

In January, engineers at the FAA’s certification office in Wichita, Kansas, certified the use of his fuel for all civil aircraft. If officials at FAA headquarters sign off, the entire civil aviation fleet could fly unleaded for the first time. In an unusual move, though, the FAA has paused the approval, asking for more data and audits.

It’s now unclear when the US can put leaded airplane fuel behind it. But Walter Gyger, who owns a flight school at Reid-Hillview, says the switch to unleaded fuel will be inevitable as pressure builds to close urban airports. “You’re going to have a much harder time defending this if your [opponents] tell people, ‘Oh, they are spraying lead over your kids’ head,’” he says. “Pilots want unleaded fuel. I don’t care about the process. I need the product.”

What you can do

Immediate action is most likely to come at the local level. Not all general aviation airports are publicly owned. But other jurisdictions already have reached out to officials in Santa Clara County about using its ban on refueling with leaded avgas as a model.

At the national level, the EPA plans to declare avgas a health hazard by 2023, and the FAA expects to approve a lead-free replacement for avgas by 2030. Deadlines like this have been missed before. Congressional pressure spurred on by voters, as well as legal action by advocacy groups such as Friends of the Earth and Earth Justice, which are pursuing the issue in court, could help ensure the timelines are met.

If you’re worried about your child’s lead exposure, local health departments and doctors can provide a simple test covered by insurance or Medicaid. All two-year-olds should get lead tests during a regular doctor’s visit. While there is no safe level of lead exposure for children, families can take steps (pdf) to minimize their exposure to lead at home and at school.

Keep learning

Read the entire Quartz investigation:

- A new generation is being poisoned

- Living where the lead is

- Do you live close enough to a small US airport to have lead exposure? Check our maps

- 50 years of research shows there is no safe level of childhood lead exposure

Have a great week,

—Michael Coren, deputy editor, emerging industries (unleaded)